Happy coincidences and old friends at Bookmark, Spalding…

Yesterday was one of those perfect days that become legendary in memory. I had travelled to Spalding, having been invited to give a signing session at Bookmark, a very distinguished bookshop which I also visited and wrote about just before Christmas last year.

There was a carnival atmosphere in the town. Christine Hanson, Bookmark’s owner, was feeling particularly happy, because hers and other businesses in Spalding had banded together to offer fun activities to passers-by in one of the yards in the Hole-in-the-Wall passageway. Christine said that it marked a significant step forward in the town’s initiative not only to save the high street but also to ensure that it thrives. She flitted back and forth between the shop and the Hole-in-the-Wall all afternoon and, despite being so busy, still provided my husband and me with her customary wonderful hospitality.

My signing session began with a remarkable and totally unexpected coincidence. Two ladies who had been paying for books at the till came over to speak to me. Noticing their accents, I asked if they were American. One of them said that she’d been born in Spalding, but had lived in America for twenty-five years. She now teaches environmental science at the University of California. Judging her to be about my age, I asked if I knew her. She said that her name was Carol Shennan. I knew the name immediately; she had lived about five doors away from me in Chestnut Avenue when we were both growing up. She said that her mother, who is eighty-nine, still lives in Spalding, and that she was just there for the week to visit her. It was an unbelievable stroke of luck that we should meet in Bookmark. Carol bought In the Family, and I look forward very much to receiving a future contribution to this blog from her when she’s read it.

Several babies came into the shop. I was introduced to Oliver, who arrived with his grandmother and aunt, who each kindly bought both books, and Harry, who came with his grandparents. His grandfather (I’m sorry that I can’t remember his name: his wife’s name is Carole) is a keen local historian and said that he doubted that my novels would cover villages as remote as Sutterton, which is where he was born and still lives. By another strange quirk of coincidence, I was able to tell him that my third novel, which I’ve just started writing, is set in Sutterton. I hope that Harry’s grandparents also will contribute to the blog when they’ve read the copy of In the Family that they bought.

My very dear old friend Mandy came in and bought an armful of books to give other friends as presents, just as she did at Christmas. At the end of the afternoon, she returned to guide us to her house, where we spent an idyllic evening eating supper and drinking wine in her garden with her husband Marc and her friends Anthony and Marcus. We ate new potatoes, broad beans and strawberries from her allotment and talked about books, teaching and cooking (Marcus is a chef). Afterwards, we drove home through the twilight. The fields of South Lincolnshire were looking at their best: the corn was just turning, and in one place acres of linseed coloured the landscape blue-mauve. The skies were as big and beautiful as always.

An idyllic day, as I said. I’d especially like to thank Sam at Bookmark for arranging the signing session, and Christine, Sally and Shelby for looking after me so well and for providing a great welcome: I heartily recommend the café at Bookmark, if you’re ever in the area. Many thanks also to the many people who stopped to speak to me – the conversations were fascinating – and for buying the books. And thank you, Mandy and Marc, for being amazing hosts and for introducing us to Anthony and Marcus, who provided me with their suggestion for DI Yates 4!

Don’t you love it when a book has personal resonance!

Stone Cradle is the second novel that I’ve read by Louise Doughty. The first, Whatever You Love, was an entirely different kind of book: a contemporary novel about child bereavement. Stone Cradle is a historical novel set in the Fens at the turn of the twentieth century, about a Traveller family. I bought it both because I’m interested in the Lincolnshire of that period and because it resonates with me personally, for reasons that I shall explain later, but first I’d like to say that any writer who can produce two such completely different, yet equally compelling, novels ticks several boxes for me straight away.

Stone Cradle is in part about the bleakness of being a working-class woman living in a predominantly farming community of the period. The story is told in the first person, alternately by a female Traveller, Clementina, and her daughter-in-law, Rose, a farmer’s adopted daughter who renounces the harsh life on the farm for the spurious glamour of running away to marry Clementina’s son, Elijah. It is one of the poignant ironies of the book that, although they share a great deal in common (including the fact that Elijah is illegitimate and Rose herself the illegitimate daughter of a mother who, like Clementina, worked hard to keep her), she and Clementina detest each other from the moment that they first meet. This is partly because they are rivals for Elijah’s affections, even though he is more often absent than present from their lives and both know that he is a ne’er-do-well, but even more because the norms and values of each are incomprehensible to the other. The dual first-person narrative captures this cleverly and is the more accomplished for going over the same events twice, through the eyes of each, without being repetitive. As someone who is experimenting with this technique at the moment, I know how difficult it is to pull off!

Rose persuades Elijah to live in a house in Cambridge (where Clementina presents herself as an uninvited guest and never moves out) for several years after their marriage, but Elijah’s fecklessness and their consequent poverty force them eventually to re-join the Travelling community. Rose never fits in. She dies twenty years before Clementina. At the beginning of the novel, Elijah, himself now an old man, is shown burying his aged mother. To save a few shillings, he has Rose’s grave opened and Clementina’s coffin laid on hers. Had they known, both women would have been appalled; the act epitomises both Elijah’s insensitivity and the privation that has followed them throughout their lives.

Two further qualities make this novel exceptional: the brilliant way in which Louise Doughty captures what it was like to be a member of the nineteenth-century Travelling community and her depiction of the period itself. The book has obviously been extensively researched, yet nowhere does the author parade her knowledge. One of the reasons for my being more often than not equivocal about historical novels is that, unless the author is very skilled indeed, the reader is presented with an outside-looking-in narrative: in other words, the author’s fictional take on what s/he has gained from the history books. Worse, this is sometimes accompanied by what I call the costume drama factor, i.e., a stereotypically ‘olde worlde’ way of making the characters think and speak, probably based on watching too many films. It takes a very talented writer not to fall into these traps, but Louise Doughty is such a writer.

Now I come to the personal resonance bit. In her acknowledgments, the author pays tribute to the Romany museum in Spalding (of which I was hitherto unaware) and the Boswell family. She actually gives the most noble of the Romany families in the book the name ‘Boswell’. It is another of the novel’s distinctions that the Traveller characters are not over-sentimentalised. There are rough and feckless Travellers, as well as ‘good’ ones, just as there are good and bad ‘gorjers’ (non-Travellers) living in and around Cambridge. The Boswell family was well-known in the Spalding of my youth. Their patriarch, whose first name I don’t know, because he was always referred to as ‘Bozzie’, had ceased to travel and built up a profitable scrap-metal business just outside the town. By the time I was born, he was reputed to be a millionaire and lived in a very nice house. I went with my father to see him on several occasions. In those days, I think that at least some of his family were still Travellers, and some may be still. Louise Doughty seems to indicate, however, that there is still a permanent Boswell presence in Spalding and evidently the Boswells were the inspiration behind the museum. I am determined to visit it next time I go to Spalding.

Taraxacum, much maligned…

In my lifetime, dandelions seem to have been always despised. My father, a keen gardener who also kept an allotment, would survey his realm with gimlet eye and hoik out offending juveniles before they could take hold. My husband does the same. Although my friends and I, as children, presented bunches of wildflowers to our mothers, they never included dandelions. Later, my son was similarly selective. Playground wisdom used to say that touching a dandelion in bloom made you wet the bed – though picking them to blow away the ‘clocks’ later in the year was not deemed to have a similar effect. (It occurs to me now that the products of this latter activity must have sprung up afterwards to annoy my father.) We picked the daisies and buttercups that grew in profusion on the banks of the Coronation Channel that skirted Spalding, then an excitingly isolated place to play (mothers in those days worried neither about accidental drowning nor ‘stranger danger’), but not the dandelions. The only time that I took any interest in a dandelion was when someone told me it would make a good meal for my tortoise, but, accustomed as he was to a townie’s diet of chopped tomato and lettuce, he turned up his nose at it. Suspicion confirmed: dandelions were weeds, and useless.

As I said earlier this week, we’ve had a very strange spring. Some plants have flowered late, others early. Some seem to have flourished; others have struggled to survive. Dandelions are hardy plants – they keep on flowering for many months, their succession of new buds clinging close to the soil and evading even the mower’s blades; the tiniest portion of root becoming a new plant within days. A couple of years ago, I even saw one blooming a few days into the new year, its head poking through a dusting of snow. They are stubborn survivors. But this spring they haven’t needed to put up a fight to survive: instead, they have been having a ball! They must have relished all that snow and rain. They are popping up everywhere, their dark leaves glossy and luxuriant, their perfect heads glimmering like star-cut diamonds. I am reminded of the beautiful picture of a dandelion and hare in Kit Williams’ gorgeous puzzle book Masquerade, a botanically accurate depiction so lovingly executed that the artist must have valued the plant. One of the fields that the dog and I walk through daily is luminous gold, the dandelions so profuse that they might have been planted deliberately as a crop. (When he saw the glorious vision, he became puppyish with excitement and whirled round amongst the flowers, coming back to me with legs stained with their colour!) Their beauty is captivating, though I know their days are numbered: the farmer who owns the field will either cut them down with the grass or send in the cows to do the job.

Drinking in their splendour, I wondered how a farmer’s wife of two or three hundred years ago might have reacted to this sight. Dandelions first flower at the time of year that earlier generations dreaded as the notorious ‘hungry gap’, the period when all the fresh produce grown for the winter months was exhausted and the current year’s crop of vegetables had yet to mature. Diets became meagre and unbalanced; sometimes people suffered from hallucinations or showed other signs of malnutrition. I have no proof, but my guess is that such a woman would not have despised this fine display, nor turned her back upon it. I’ve just looked up ‘dandelion’ in my herbal, and discovered that the leaves can be used in salads, or cooked in soups and stews. The heads can be fried, or dried and then crushed as condiments. Dandelion wine has a powerful kick. Dandelion infusion makes a fine herbal tea. Dandelion roots, roasted and ground, can be used as a substitute for coffee, much like chicory roots. Dandelions are also reputed to have medicinal properties and, for generations, were used to cure or alleviate a wide range of ailments. I discover that the dandelion was only downgraded to the status of ‘weed’ at the end of the nineteenth century. Like the tortoise, we have turned into townies. Will the twenty-first century let the tide of fashion turn again and restore the reputation of the dandelion?

In the meantime, I’m going to enjoy the spectacle of their blooming profusion and look for a hare (quite common here) leaping over them.

I’d like to knock down that Victorian edifice…

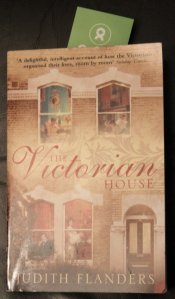

Taking up the theme of food again, I’m still reading about Victorian houses and customs in order to get a feel for how the very old people whom I knew in my youth grew up. One of the things that strikes is me is how indelibly the Victorian age made its mark on those who were born within it. My grandmother was born in 1892 and was nine when Queen Victoria died, yet all her life she was a Victorian. She even dressed like one, in ankle-length skirts and pastel-coloured blouses trimmed in lace, with high collars.

Not only did Queen Victoria’s reign seem to imbue everyone who lived in it with norms and values that were immediately spurned by the next generation, but it succeeded in erecting an almost insuperable barrier between itself and the age which preceded it. The most alarming thing of all is how women seemed to become walled up as part of this process.

They were literally walled up: condemned to stay in the house almost all of the time, maintaining and cleaning it or supervising its cleaning and maintenance, depending on their class; spending each day of their lives ensuring that the master of the house returned to a perfectly-kept residence. This in itself would have been irksome enough, but social aspirations added to women’s domestic workload in the most intolerable way. In an age when the middle classes were burgeoning, so that many people had more of what is now called ‘disposable income’, and when, for the first time, machinery could churn out materials and finished goods very cheaply, houses became filled with all kinds of artefacts, many of them quite useless. Whether they were bought or made at home, all of these things also needed care and maintenance – the latter involving a great deal of washing and cleaning when houses were warmed by coal fires and lit by candles or gas. Clothes and food became much more elaborate. Women were not only not allowed to go out to work, they felt compelled to spend every waking hour carrying out tasks which today we would regard as of minimal value or even futile. Meals in middle-class households consisted of many dishes. When providing food, the housewife was expected to achieve an illogical combination of outward show – especially when there were guests at the table – and the practice of frugality. This often meant that the same food appeared on the table several times running before it was finally consumed, each time ingeniously and time-consumingly served up in a slightly different way.

I’ve often reflected that, to a greater or lesser extent, all except the very young spend some of their time living in the past. Although my own and my husband’s tastes in furniture are quite traditional, and therefore most of our possessions have not dated all that much, I know that the décor and soft furnishings in my house are very much of the period at which we moved in to it in 1994, and that visitors will recognise this. It is a phenomenon that was yet more true of previous generations: they thriftily kept the same furniture until it had, quite literally, worn out. And it wasn’t just the surroundings that belonged in the past; attitudes, values and points of reference were also behind the times. Exactly how far behind often depended on location, sometimes also on education. In London at the turn of the twentieth century, the Bloomsbury Group famously rejected the lifestyle and morals of their Victorian parents; however, Victorian lifestyles and morals were still alive and well in the Spalding of the 1950s and 1960s. It took the combination of the pop scene (I don’t just mean the music, but everything that went with it) and the advent of the first working-class generation to be university-educated to instigate real change.

In some ways I feel privileged to have lived through all of this and, through aligning my reading with my own memories, to have come, belatedly, to some kind of understanding of it. Women today still complain about glass ceilings and the impossibility of ‘having it all’. True equality has been a long time coming and is not quite here yet. The journey was started by those Victorian girls who were allowed just enough education to understand what they were missing. Some nineteenth century women were so frustrated, or so badly treated by their husbands, that they turned to murder (the weapon of choice was poison), knowing that the death penalty would surely be their fate if they were caught.

What I’d really like to be able to do would be to travel back to the past and knock down that huge Victorian edifice, as the Berlin Wall was knocked down, in order to be able to see beyond it to the Georgian age that preceded Victoria’s. I wonder what those women, in their lighter, brighter, more sparsely-furnished houses, were like; whether they led happier lives than their Victorian descendants; whether knowing them better would prove the hypothesis that civilisation develops, not in linear fashion, but in loops and curlicues, like oxbow lakes. The Victorians, so enterprising in so many ways, were out there in their boats, not realising that they were grounded in a swamp.

Wicked Uncle Dick

Yesterday I mentioned that I have recently bought several books about South Lincolnshire to aid my research. One of these is Aspects of Spalding Villages, by Michael J. Elsden. It is a book of photographs with quite an extensive accompanying text drawn from contemporary newspapers and other documents, such as old trade directories.

Among the many fascinating sections is one on Pode Hole, a hamlet between Pinchbeck and Spalding, which became important when a pumping station was set up there in the late eighteenth century to reduce the threat of flooding. It was a place to which I often headed when out on bike rides. Its system of sluices represents a complex and quite awe-inspiring feat of engineering. However, of more interest to me were the rather quaint by-laws relating to the pumping station, which were posted in full on a board in front of the main building. When I visited Spalding shortly before last Christmas, I was intrigued to see that the by-laws notice is still there. It’s a sturdy production, set in stone like a fenlands version of the Ten Commandments.

The section in Michael Elsden’s book that is headed ‘Trades and Business People in Pode Hole in 1937’ includes the entry ‘Sherrard, Rd. Albert, haulage contractor, Pode Hole’. It leapt out at me because Richard Sherrard (whose middle name was also his father’s – I had not previously known that he also bore it) was my Great-Uncle Dick. When I knew him, he led a fairly down-and-out existence. He scraped a living by farming a small-holding at Spalding Common and lived in one of the short streets of council houses there. I don’t recollect having had any meaningful conversations with him as a child; the Sherrard men were not particularly interested in girls. However, my brother, the only boy of our generation, was regaled with all sorts of treats and confidences. When we were both adults, he told me some of the family history that he had gleaned from Uncle Dick and his two surviving brothers (the eldest brother, John, had been gassed in the Great War and died in the 1920s). He said that Uncle Dick had told him that he was once the owner of a thriving haulage business, with a fleet of lorries that carried vegetables and livestock across the Fens. More roguishly, he admitted that he had plied a flourishing black market side-line during the Second World War.

I only half-believed this tale, because the Uncle Dick that I knew was anything but a prosperous businessman. I therefore rather assumed that it had been invented to satisfy a small child’s curiosity and also to imbue his old uncle with a touch of glamour. (‘What did you do in the war, Uncle Dick?’ ‘Oh – ha, ha, ha – I was a bit of a scoundrel; I sold stuff on the black market. It didn’t harm anyone; I just helped people to get the things that they needed.’) Now, however, I have found proof that at least some of Uncle Dick’s story was true: he was indeed a haulage contractor. The question is, did he really own a fleet of lorries, or just one antiquated, clapped-out lorry that was pressed into service for the war effort? And, if the former, what happened to them all? Might they have been confiscated because his nefarious activities were found out? Might the haulage business even have gone downhill because he was disgraced, or sent to prison? I don’t suppose that I shall ever find out and, since my own version of events is probably more colourful than the truth, I’m not sure that I really want to!

Into the Fens again!

Yesterday, I made my second East Anglian excursion of the year, this time to Cambridge. It was a bitterly cold day and, although it was dawn by the time that I reached Peterborough, the light remained subdued by one of those swirling mists that often accompanies sub-zero winter days. I did not enjoy the cold (it was impossible to get warm, even by wearing a coat on a heated train), but I was delighted by the mist, as it enhanced the jolt of surprise that Ely Cathedral always springs when it sails suddenly into view. Not for nothing is it called the ‘Ship of the Fens’ and yesterday it truly looked like a huge galleon that had just weighed anchor on a white-capped sea.

Whilst Ely is one of the country’s oldest cathedrals (parts of it date back to the seventh century), the Fens as a whole are famous for their beautiful churches. When I was a child, every shopping expedition to Peterborough included a visit to Peterborough Cathedral. It was here that I first learned of the beheading of Mary Queen of Scots at Fotheringhay. She was originally buried in Peterborough Cathedral, though later exhumed and reinterred, by order of James I, in Westminster Abbey.

However, some of the finest Fenland churches are not cathedrals, but the more modest – although still magnificent – parish churches. I was both baptised and married in the Parish Church of St. Mary and St. Nicholas in Spalding; I was a pupil at Spalding Parish Church Day School, affiliated to this church.

I have recently acquired several books about South Lincolnshire in order to research Almost Love, my next novel. Among these is Geese, Gowts and Galligaskins, by Judith Withyman, a history of life in a fenland village from the mid-sixteenth to the mid-seventeenth centuries. (I shall review it when I’ve finished reading it.) Most of the papers that she draws on, in this vivid re-creation of how people lived in the Fens three or four hundred years ago, were discovered by her in the 1970s, in a chest kept in St. Mary’s Church at Pinchbeck, a large village that has become almost a ‘suburb’ of Spalding.

Such records are treasures and I wonder how many other Lincolnshire churches contain such secrets that are silently waiting to be yielded up to the interested and observant?

The old curiosity shop…

I’ve been asked by several readers of In the Family about the shop where Doris Atkins lived; it was also, of course, the place where she was murdered. As I’ve written in a previous post, this shop was drawn almost entirely from my memories of the establishment that my great-uncle kept when I was a child. My grandmother lived there, too, and was effectively the housekeeper. It was the house in which they’d both grown up. My great-grandfather died in the 1930s, but my great-grandmother was still alive when I was born. I have a very vague memory of her sitting up in bed, a tiny frail old lady with waist-length snow-white hair. She died a horrible death by falling on an electric fire.

The shop itself had been the front room of the fairly substantial family home, built, I’d say, in the mid-nineteenth century. It would be incorrect to call it a terraced house; it was rather one of those houses that you still find in some old towns: detached, but snuggling right up to its neighbour. The neighbouring building on one side was a much smaller, newer house; on the other, the Punch Bowl pub (where dancing lessons were held on Saturday mornings: my grandmother tried in vain to persuade me to learn tap-dancing). The address was Westlode Street, as in the novel. I’ve since discovered that this is the only street in the country bearing this name.

The shop itself was relatively modern. Although my great-uncle was a Scrooge-like character (he would give my brother and me packets of out-of-date jelly babies and dolly mixtures at birthdays and Christmas), he had spent some money on modernising it, possibly because he’d once run foul of the environmental health department at Spalding Council. My grandmother was certainly an obsessive cleaner and scrubbed the floor and all the surfaces in the shop every day. The bay windows on either side of the door had been converted into ‘picture windows’ that took displays. There was a tall, glass-fronted cupboard which was filled up every day by the Sunblest man with loaves of bread, tea-cakes and currant loaves. He usually also brought a tray of cream cakes. The cream was all the colours of the rainbow; I shudder now to think of the dyes that must have been used in these creations. Another daily visitor was the pop man: my father told me that his visits had removed the need for the shop to make its own carbonated drinks; as a schoolboy, he and his friends had had fun making fruit sodas three times as effervescent as they should have been!

The shop also had a manual ham and bacon slicer – one of those fire-engine red machines with a lethal circular cutting blade to be seen in most general shops of the time – and several fridges, including a shiny rectangular-shaped Frigidaire with a glass display front that was great-uncle’s pride and joy. It did not impress me as much as the squat, square fridge in which he kept ice-cream. I was intrigued less by the contents than by the mystery of its black rubber lid; this was several inches thick – presumably for insulation purposes – and too heavy for a child to lift (which may have been part of its attraction for its owner – there was no risk that his great-nephews and -nieces would plunder the stock).

Pocket-money sweets were laid out in trays near the till, right under great-uncle’s nose. He always wore a long, dun-coloured shopman’s coat and was rarely seen without his trilby hat. When he wasn’t busy serving, he sat in the shop on a tall stool, painstakingly writing out the price-tags that were stuck into meat and vegetables on vicious-looking skewers. He had a few secrets under the counter, too. For years I wondered what the box labelled ‘ONO’ contained and why my mother was so cross when I tried to look inside it. It was only after I had left home that I read in a novel that this was the brand-name of a type of contraceptive.

But the crown jewels of the place, for me and for all children who visited, were the serried ranks of tall sweet jars that stood on shelves along the back wall. They were uniform in size and shape, with thick lids of many colours – perhaps made not of plastic, but of one of its predecessors, such as Bakelite. They contained bulls’ eyes; mint imperials; Fox’s Glacier Mints; Nuttall’s Mintoes; Bluebird liquorice toffee; Milk Maid dairy toffees; aniseed balls; gobstoppers; red liquorice strands; black liquorice strands; winter mixture; chocolate Brazils; Liquorice Allsorts; Payne’s Poppets. I could go on. They looked so beautiful standing there together, a hymn to the confectioner’s craft. Choose a quarter of any of them – it would be conveyed by a tin trowel to a narrow, trough-like pair of scales – and their spell was broken. Their real charm was collective; it resided in their magnificent diversity of shape, colour and size. They inspired a sort of sensory holy grail quest that making no single choice could ever satisfy, because their pull was visual as well as visceral.

I had hoped to write about the house behind the shop, but I’ve probably said enough for now. I’ll come back to it in a future post!