The Heritage Murders and an invitation…

The Heritage Murders, the third DI Yates novel to be published by Bloodhound Books this year, came out yesterday. The others, The Sandringham Mystery and The Canal Murders, were published in April and July respectively.

The novels have attracted a great deal of interest and I am hugely grateful to all my readers and to Bloodhound for producing and promoting them so magnificently. Nearer to Christmas, they will also be on sale as a boxed set. For the moment, it seems appropriate to me that The Heritage Murders should appear right at the start of the autumn. Soon the nights will be drawing in and books will become an even larger part of readers’ lives than at other times of the year.

As readers of this blog will know, I rarely use it to promote my own books. I shrink naturally from boosting myself and I am much more comfortable in writing about the work of other authors or interesting encounters I have had with other people or unusual places I have visited. However, now I have a new publisher, it is important for me to find a wider audience and to attract some new social media friends (those I have already made have been hugely supportive of both my books and my blog) in the UK and America and other English-speaking countries. I visited New York in July and have made a start!

If you are a blogger based in the US or UK and would like to review one of my books or perhaps to invite me to write a guest article for your blog – or, if you are an author, review one of your books – I should be delighted to hear from you. Similarly, I am very happy to write articles for booksellers and librarians, magazines and newspapers. If I can be of help to you by entertaining your existing readers or by extending your reach, just let me know!

Finale to my National Crime Reading Month daily blog series

Today is the last day of June and therefore today’s is the last of my daily blog posts to celebrate Crime Reading Month. I’d like to pay tribute to the CWA for coming up with the idea of CRM and to the countless people who have supported it. I’d particularly like to thank everyone who has contributed to these thirty posts by providing so many magnificent insights and vignettes and for giving up their time so generously to help me. It’s impossible to pinpoint highlights – I feel as if I’ve been on a high all month! – although a few moments stand out for me personally. I was struck by Hannah Deuce’s comment that all writers are different, so she supports each one in different ways; by Natalie Sammons’ observation that if you write to please yourself, you won’t be disappointed ‘whatever the outcome’; and perhaps most of all by Frances Pinter’s description of Brexit in one punch-packing word: ‘frivolous’. Frances’ post was all about the importance of peace and how we should dread the danger of war that is looming once again; sadly, as we reach the end of this month, the conflict in Ukraine is no nearer to resolution than it was on 1st June.

CRM has given me some humbling opportunities to read or re-read some fine works of fiction: Snegurochka, by Judith Heneghan, and The Manningtree Witches, by A.K. Blakemore impress with their originality and fine use of language, but I have enjoyed all the novels that I have written about this month and am in awe of all their authors. In this, I include Annie, the only poet featured, whose stark poems about domestic violence bring home the enormity of it more vividly than any number of newspaper and court reports. I’d also like to pay tribute to those who have always supported me as a writer and continue to do so: Annika, Valerie, Noel, Dea and now, Hannah, please take a bow. I salute those who have dedicated their lives to supporting the bookselling and publishing industries: Richard, Nick, Lynette, Linda and, again, Frances and Noel. I’d love to be a member of Deirdre’s reading group – she and her book club friends seem to have such fun! And finally, I’d like to thank Betsy, Tara and Hannah for publishing The Canal Murders to the usual high Bloodhound standards; and I’d like to take the opportunity to apologise for (temporarily) having forgotten my own publication date!

As readers of this whole series of posts will know, I have been privileged to speak at four libraries during the course of the month. I have, of course, known for many years how much librarians bring to their communities, but when I met Helen, Kathryn, Tarina and Kay and their teams, their generosity, talent and tireless efforts to help people were brought home to me all over again. I’d like to thank them once more for their wonderful hospitality – and the equally wonderful audiences to whom they introduced me, each of which taught me far more than I felt I had to offer them. I now know about ran-tanning, the use of opium for Fenland agues and many more facts about life in Lincolnshire, both past and present, than when I started out. The library visits also gave me the opportunity to research some unsolved Lincolnshire murders, including that of Alas! Poor Bailey, my favourite. My encounter with the vicar of Long Sutton church will stay with me.

When I introduced this blog series, I promised to tell my readers at the end of it why I write about the Spalding of my childhood even though my novels are set in the present. I renew that promise now, but I hope you will allow me a short delay. It is because – as I mentioned earlier this week – I am currently on holiday in Orkney – in fact, sadly, my time here is drawing to an end; and while I am still able to imbibe the magic of this place I should like to introduce you to one of the island’s serial murderers – the great skua. Called “the pirate of the seas” or, in Orkney, “the bonxie”, this formidable bird – which appears not to be afraid of humans – hunts other birds on the wing. Today my husband and I watched spellbound as a pair of great skuas systematically chased a curlew through the soft blue skies and engaged above and around us in aerial combat with greater black-backed gulls. I came to Orkney for inspiration as a writer and I have found more here than I could ever have dreamed about.

As I prepare to return home and submit myself to the discipline of the keyboard once more, I should like to conclude by thanking everyone who has read even one of these posts. I do hope you have enjoyed them. There are more to come – I was surprised and grateful to have more offers from would-be contributors than there are days in the month of June. And of course I shall not forget my promise.

I leave you with a cheerful picture of one of Orkney’s denizens.

The Manningtree Witches, by A.K. Blakemore

Sometimes you can go a longish stretch without reading a book that really amazes you – a book that fills you with awe, one that you can truly say you ‘love’. Then such a book comes along and the gratitude and pleasure that you feel is redoubled by the wait. Such a book for me is The Manningtree Witches, A. K. Blakemore’s debut novel and one of my spoils from this year’s London Book Fair. I read it early in May after many weeks’ fare of enjoyable, well-made and admirable books, none of which, nevertheless, quite reached the heights that this novel achieves.

The Manningtree Witches is classified as historical fiction, but it is as surely a work of crime fiction. It tells of the witch-hunts pursued by Matthew Hopkins, the self-styled Witchfinder General, in the seventeenth century. It is a novel at once lovely and appalling, the world which it depicts a place of ingenuousness and sin, white magic and black magic, faith and cynicism. Blakemore weaves her tale in words that are elaborately rich and beautiful; the speech the characters employ is a brilliant reconstruction of the language of people who lived only a generation or two after Shakespeare, a serious and melodious tongue which sometimes conceals, sometime reveals the decadence at the heart of their society. It was no surprise to me to learn that Amy Blakemore is also a distinguished poet.

Rebecca West, the protagonist of the story and also its narrator, is a survivor. Clear-eyed and intelligent, she is capable of weighing shrewdly the characters and personalities of those around her – though she is not without her weaknesses, among which is her girlish infatuation for Master John Edes, the church clerk. Eventually Edes takes advantage of this, but he is too cowardly to acknowledge their intimacy. Rebecca is ahead of her time in understanding whence springs the muddled superstition that governs everyday life:

“I am not superstitious – I am useful. I have taught myself to watch and listen. I have seen enough suffering in my life to know that the diseased mind is prone to invent all manner of phantoms that might hover over a person. Better to blame a sprite or a puck for the souring of the milk or the tangles in the horse’s mane than to concede one’s own slovenly habits may have contributed to the situation.”

Rebecca’s intelligence shines out, making her superior to the other women in the novel, all of whom are seen through her eyes. Generally, the female characters, for all their coarseness and jealousies, are morally superior to the males, but also more vulnerable. The following short passage conveys the condescension and cruelty of Hopkins and John Stearne (“the second richest man in Manningtree”):

“At that moment Misters Matthew Hopkins and John Stearne emerge from the dock office across the way, lovely furs frothing at their collars in the spry wind and begin to pick their way along the road. They pass the women with a reluctant tipping of their hats, like crows’ sharp heads to a wound.”

There is also implied hypocrisy here, though Hopkins gradually emerges as a complex character, perhaps – but only perhaps – as deluded and vulnerable as his victims.

The Manningtree Witches is the best historical novel I have read since The Miniaturist (and that was published more than six years ago!). It won the Desmond Elliott prize in 2021. I am certain that Amy Blakemore, who is only at the start of her career as a novelist, will go on to win many more prizes and accolades. She is already one of the best novelists of her generation.

The Good Life, by Sarah K. Stephens

This is a classic ‘woman at risk’ crime novel with a great twist at the end. It combines the woman-at-risk sub-genre with a newer trend in crime fiction – the portrayal of protagonists endangered not only by evil adversaries but by having been pushed by circumstance to the farther reaches of civilisation. In this respect it reminds me of Claire Fuller’s Our Endless Numbered Days.

Kate, the heroine, is a woman at war with herself, plagued by self-dislike. It has been triggered partly from the disappearance of her toddler son a few years before the novel begins, forcing her to confront the fact that she was a ‘bad mother’, and partly from much further back in her life, when the child she was babysitting as a teenager died. The boy choked on fruit Kate had assembled to make a smoothie while he was in her care.

Calvin, Kate’s husband, takes her to an expensive – but somewhat tawdry – holiday resort in Costa Rica, for a much-needed break and to try to rekindle romance in their strained marriage. On the flight there they meet an over-friendly couple, Ashby and Bill, who it turns out are staying at the same resort. Kate throws herself enthusiastically into cultivating this new friendship. Calvin is not so sure. Then, after a night of heavy drinking, the nightmare begins. Rebecca, Kate’s sister, comes to her aid, but very soon she, too, becomes a casualty.

The novel explores the themes of redemption and self-respect and how they are connected. It shows how wrong choices can be made, relationships damaged – and, sometimes, lives curtailed – by the reckless behaviour of people who believe they don’t matter. It looks at both selfishness and selflessness from surprising new angles.

I found Rebecca by far the most interesting character in the novel, even though there is much more space devoted to Kate. Rebecca remains enigmatic until the end. The female characters in general are drawn in more detail than the male characters. Ashby Garcia, who turns into Kate’s nemesis, fascinates from the start with her hard glamour. This is the passage which set Kate on her nightmare journey:

The woman had the aisle seat, just like Kate, and so Kate shoved her hand out across the space, ignoring the soft bustle of the other passengers surrounding them. “I’m Kate Whitaker.” Their hand intertwined into a firm handshake. Kate felt a pinch as wedding rings dug into her hands. A stack of Bulgari chokers decorated the woman’s long neck.

“Ashby Garcia.” She flipped her hair over her right shoulder, one shiny curtain of good grooming. “This is my husband, William.”

The passage is understated, but you can just feel that things won’t end well, can’t you?

If you have yet to select books for holiday reading this summer, I can’t recommend The Good Life too highly.

In which I almost miss my own publication day!

This morning I got up at 4 am, just as the day was dawning, rejoiced in the singing blackbirds, took a quick look at the BBC news – complete with midsummer celebrants at Stonehenge – and spent almost four hours facilitating a webinar featuring librarians from Australia and New Zealand. As you do, when you live at the wrong side of the world. 😉

By 9 am, all the librarians had signed off and I was looking forward to breakfast, but I could see emails in my Outlook and thought I’d read them first. (I can never resist that little yellow envelope symbol – it has encroached on my writing time on more occasions than I can remember.)

And there it was. A message from Hannah, the lovely marketing manager at Bloodhound: I just wanted to pop you over an email to say congratulations on your publication day for The Canal Murders! I hope you are able to find time to celebrate today.

Reader, I had forgotten the publication date of my own novel! Duh!

That doesn’t mean to say that I am not over the moon. I’m humbled, too: everyone at Bloodhound has been beavering away while I have been focusing on the Antipodes. Not that I regret that, but clearly I need to do some serious work on my multi-tasking skills.

As readers of this blog are aware, I have given several library talks recently. It has been striking how often members of the audiences have asked me how I got the idea for a particular book. What was the initial spark that started off the creative process? What triggered the gleam (or grit!) in my eye?

The Canal Murders was inspired by several separate events and discoveries. A few years ago – pre-COVID – I was asked to give a talk at the main library in Lincoln and had time beforehand to explore the beautifully restored waterways in the city. I’m interested in canals – I’ve taken several narrowboat holidays – and have read about the Fossdyke, the ancient canal originally dug by the Romans that connects the River Trent to Lincoln at Torksey; and because I’m interested in canals, I have also read about two murderers, one based in Yorkshire and the other in Greater Manchester, who have made use of the canal network to dispose of the bodies of their victims (I won’t identify them, as I have used aspects of their real-life crimes in the novel and I don’t want to give too much of the plot away). When I was thinking about this novel, I had also been reading about copycat murders and how their seeming lack of motive creates extra obstacles for the police when trying to track down the killer(s). Yet another theme came from some items of farming news in East Anglia at the time, about soil erosion and the need to take proper care of the land. This is also woven in.

The novel has a multi-layered plot, because there are several murders, each featuring a different type of victim. And the sub-plot – in response to requests from readers – focuses on DS Juliet Armstrong’s private life.

I hope that you will think this sounds intriguing. I rarely write about my own books on this blog, but perhaps you will forgive me on this occasion, as The Canal Murders has been published during Crime Reading Month, the focus of all my June 2022 posts, and it’s also been published on Midsummer’s Day. I can think of no more propitious date on which to launch a murder mystery. The gods will surely raise a cheer, awoken from their slumber as they have already been by the votaries at Stonehenge!

More to the point, Hannah has been cheering The Canal Murders, too, in her own quiet but indomitable and infinitely more practical way. Thank you, Hannah, for all your inspired work and for being a much better multi-tasker than I am.

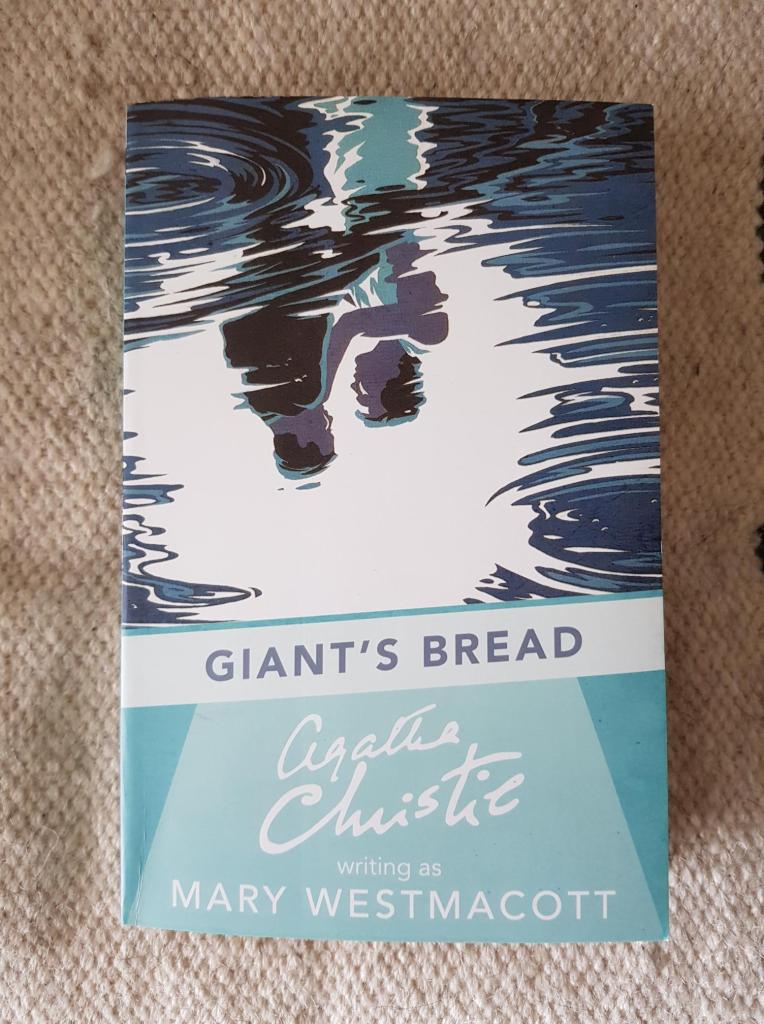

Giant’s Bread, by Agatha Christie writing as Mary Westmacott

I knew that I couldn’t write a blog post every day for a month to celebrate CRM without including something about Agatha Christie, the Queen of crime fiction herself. It’s some time since I read any of her books and I’m not familiar with all of them: of the ones I know, like other people I’ve interviewed, I like The Murder of Roger Ackroyd best.

However, although I have long been aware of them – and, indeed, as a library supplier used to sell them – I was unfamiliar with all the Mary Westmacott novels. I remember reading once that Christie’s publisher encouraged her to write under several pseudonyms – there is at least one other besides Westmacott – because she was so prolific, to avoid flooding the market with Christies. This may have been part of the reason: it is also true that the Westmacotts are not billed as crime, but as mysteries. Despite this, I hope that my readers will indulge me by allowing me to review one of them here, instead of a more traditional Christie murder story. The one I have chosen is Giant’s Bread – mainly because I saw a dramatisation for radio advertised recently.

It is one of the most puzzling novels I have ever read. Christie is famous for her lack of interest in character development, but she gives her protagonists – particularly the women – some very individual attributes in this book. It could not, however, be described as conventional character development: rather the twists and turns of the characterisation seem to be adapted – and in fact are subservient to – the demands of the plot.

This is not all that is unusual. The book was first published in 1930 and is set before, during and in the years that follow the First World War. Yet the character of Nell Vereker – and the choice of a first name that is reminiscent of Dickens’s saintly Little Nell may not be accidental – in the first chapters seems to hark back to the weak and dependent but ensnaringly pretty female characters beloved of nineteenth century novelists. Nell is Dickens’ Dora Spenlow or Wilkie Collins’ Laura Fairlie, spiced up just a little with a sprinkling of George Eliot’s selfish Rosamond Vincy.

Having been tempted by the offer of marriage from a rich American, Nell decides to marry her true love, Vernon Deyre, an impoverished aristocrat who knows he will not be able to afford the upkeep of Abbots Puissants, his ancestral home, when he inherits it. In young manhood, Vernon has ‘discovered’ music and yearns to be an avant garde composer. He knows that marriage to Nell is likely to jeopardise this ambition. Then the war intervenes and Nell is suddenly transformed into Marion Halcombe: she becomes a dependable, serious, hard-working nurse. Vernon, sent to the front, deplores her wish to play a useful part in the conflict and thinks she should be socialising in London instead. It is an interesting feature of the book that men repeatedly cast Nell as a priceless ornament who should not be expected to sully her pretty hands: yet she is at her best, and only truly comes alive as a character, when she defies such stereotyping.

Jane Harding, the other main female character in the novel and a rival for Vernon’s attentions, is a different type entirely. She epitomises the ‘new woman’ that other early twentieth century novelists have described. She is a Cassandra-like figure who sees everything clearly and always speaks her mind, often quite brutally. Yet, like Nell, she also has roots in nineteenth century literature. Like Trollope’s Mrs Winifred Hurtle in The Way We Live Now, she is a ‘fallen woman’. She has lived, firstly, with a theatrical impresario who treats her cruelly, and then with Vernon himself. Vernon ditches her without a second thought when the ‘pure’ Nell re-enters his life.

I won’t give away any more of the plot – which bears the authentic Christie hallmark of being tortuous but credible. What I have described so far indicates that this novel tackles some very serious themes: infidelity, domestic violence, the artistic imperative that demands selfishness to succeed, the confused and often demeaning roles occupied by women in early twentieth century society and the unequal – with either gender sometimes prevailing – relationship between the sexes. It also touches on themes that seem very contemporary: PTSD (although of course the name is not used) as it afflicts returning soldiers, antisemitism and the impossibility of ‘having it all’.

What’s not to like? Well, the jejune upper crust slang grates on the modern reader. Dialogue is peppered with “I say”, ‘beastly’, ‘frightful’, ‘horrid’ and so on, which sometimes makes it hard for readers to take seriously some of the more profound comments made by the characters. The plot, despite the ingenious tergiversations, is a bit disappointing – though perhaps that’s because I was waiting for a murder that never materialised, unless you count the murder of the soul. And those sudden character changes I have noted, especially in Nell and Vernon (though his are triggered by illness), can be hard to swallow. However, I think that Westmacott is breaking new ground here: if it doesn’t seem too fanciful, I think she is taking the reader on a tour of nineteenth and early twentieth century society as represented by the novels of those eras and sending it up. In other words, I think that Giant’s Bread works on several levels; and at one level it is a social satire.

The writing often shines. Here is Vernon’s mother, making the most of his funeral:

“She stared ahead of her through blood-suffused eyes in a kind of ecstasy of bereavement.”

Whereas this is how Nell, the (truly grieving) young widow, reacts to the occasion:

“Again Nell felt that wild desire to giggle. She didn’t want to cry. She wanted to laugh and laugh and laugh… Awful to feel like that.”

Which reader would not sympathise with Nell?

Giant’s Bread is an experimental novel, unlike The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, which, although ingenious, sits firmly within the traditional crime fiction genre. Does it work? I would give it 8 out of 10, whereas Roger would always score 10.

The gold of reader loyalty

Were I to say that readers are not unimportant to writers, I’d be providing you with an extreme example of litotes. Readers are an author’s lifeblood. If a novel has no readers, it barely deserves to be called a book, just as a portrait kept forever in the dark is scarcely a picture. I feel blessed that as a crime writer I have been ‘discovered’ by some loyal readers who have subsequently read and reviewed all my books. No one has been more staunchly supportive of my work or sympathised more with what I have set out to achieve than Valerie Poore. Recent posts of mine have featured Fraser Massey, a fledgeling crime writer and Mickey J Corrigan and Sarah Stephens, two established writers whom I’ve never met in person. Similarly, I have never met Valerie (a couple of times, on my way through Holland, I tried to visit her on her vintage Dutch barge in the Oude Haven in Rotterdam – there are two links here – but, sadly, on those occasions she was not there). I know she supports other authors as well as myself. I have asked her to write a short post on why she is so generous with her support for others – and how she finds the time to do it!

For several consecutive years, I’ve looked forward eagerly to each of Christina James’ nine crime novels. If I remember correctly, In the Family, her first DI Yates book, was also the first crime fiction I’d ever read from a novelist who wasn’t already widely known in the genre. I was a detective novel fan of old and had read most of the big name authors: PD James, Elizabeth George, Ian Rankin, to name just a few. But at some point, I found the plots becoming ever more harrowing and disturbing – so much so that I stopped reading crime fiction for quite some time.

As a result, I was somewhat hesitant to start down the detective novel path again, but after meeting Christina James on Twitter and enjoying our interaction, I decided to give In the Family a try. To my delight, the book ticked all my mystery-solving boxes and I can say with some conviction that Christina gave me back my taste for crime (so to speak). It was an extra benefit that having ‘met’ her on Twitter, I could also continue to interact with her and support her writing on social media.

Since then, I’ve added several other, mostly independent, authors to my list of favourite crime fiction writers, nearly all of whom I’ve discovered through Twitter and book bloggers. And even though I’m not a crime writer, it’s still the fiction genre I read the most, so I love being able to support their books as a reader, reviewer and tweeter.

So when Christina asked what motivated me to help other authors through social media support, the answer came easily: it’s because I was an avid reader long before I became an author myself. Without exaggeration, I can say I’ve loved immersing myself in books my entire life and nothing gives me more pleasure than reading. I also appreciate others’ excellence in writing, so if I read an author whose prose, dialogue, plot development or even turn of phrase I admire, I instinctively want to tell the world about them and share my enthusiasm.

As a student and young adult, I could talk books for hours with my friends – I studied English and French literature, which helped, of course. These days, that appreciation is more easily conveyed through social media, as I no longer have the time to linger with fellow readers to the same extent; nor do I live in an environment which would tempt me to do so. My home for twenty years has been on an old barge in the Netherlands among folk whose passion is restoring historic vessels. Welding, not reading, is what lights their fires. And although I’ve written about these colourful neighbours in my memoirs, I cannot talk books with them.

My solution, then, is to share my reading discoveries on social media where I can promote and interact with the authors whose books I enjoy. But there’s a spin-off benefit too: I now belong to a community of readers and authors, many of whom reciprocate by reading and sharing my books too. Promotion, I discovered, is reciprocal. What you give is what you get, a further reason (as if I needed one) to share and share alike.

So, there you have it: someone who loves crime fiction and promotes it, brilliantly! I should add that Val is a writer of memoirs other than those of her experiences on the canals of the Netherlands, Belgium and France, for she has lived in South Africa, too. I’m adding the link to her fascinating blog so that you may wander with her if you wish! I’ve also provided two links to my posts about my visits to the Oude Haven, if you’re interested. I’ll finish with a photographic flavour of her watery life and her books about it:

Author friendships and a fine novel: The Physics of Grief

One of the best things about being a writer is the unexpected opportunities you get to meet and correspond with other writers. I use the word ‘meet’ in its widest (post-COVID) sense, which may mean Zoom or Teams meetings, webinars or online chat as well as face-to-face encounters.

I first met Mickey J Corrigan digitally – we have never met in person – in my capacity as an editor for Salt Publishing in 2016. Mickey, an American author, had written a book entitled Project XX, subsequently published by Salt in 2017. I was privileged to edit it – the book required minimal alteration from me – and the long email correspondence that ensued – and continues – has mainly been about sharing our ideas and experiences as writers. Project XX is an incisive satire about America’s gun culture, high school shootings and materialism. Sadly, it is as relevant today as it was when it was first published, as the recent Texas school massacre shows.

This single-sentence blurb describes it so eloquently that, although I can’t remember who wrote it, I am certain it must have been Mickey: “A darkly humorous story of girls on the rampage that will grip you by the throat and won’t let go until you gasp for breath on the final page.”

The main purpose of this post is not to review Project XX, however. Instead – with permission – it is primarily a page-long quotation from Mickey’s The Physics of Grief, a crime noir novel which is sadly no longer in print. Another powerful satire on the American way of life, it describes the career of Seymour Allan, a man in late middle age who is offered the job of professional griever by the mysterious Raymond C. Dasher. Seymour embarks on the strange occupation of being paid to ‘mourn’ at the wakes and funerals of some very unpopular people. He cares for a dying criminal who tries to murder him; he attends unorthodox funerals in the Florida Everglades that are probably illegal; he encounters trigger-happy gangsters and an alligator and meets Yvonne, a sexy redhead mourning her mobster boyfriend.

The Physics of Grief is beautifully written, quirky, erudite – though it wears its learning lightly – and profoundly funny. If you are a publisher and think it may appeal, please contact me and I will put you in touch with Mickey.

There were seven of us not counting the one in drag. Together but with much difficulty we managed to lift, shove and roll the massive body into the deep and muddy hole. After he had landed – with a resounding splat – we high-fived each other. It took us another hour to fill in the hole and pack down the wet dirt. Finally we covered the fresh grave with branches and brush, leaves and acorns, pebbles and small rocks, until the burial area blended in nicely with the surrounding environment.

Very much a natural burial. Except for the fact the gravediggers were most likely murderers, and the body that of a murder victim.

Also, in this case, there was no marker. Obviously, no one would be coming here to mourn their loss. Their very big loss.

As we worked, the night had closed in around us. The hum of mosquitos had died down and the crickets were singing from the trees while tiny bats swooped overhead. An arc of juvenile egrets swept upwards with a whoosh and flew off together. The moon rose in a silver sliver and bright stars popped out across the black sky.

The men talked among themselves, joking around and laughing. When I finished up I stood off to the side, scratching my bug bites while they smoked cigarettes and chatted. I tuned them out. I didn’t want to know. All I wanted was to get away from them in one piece. But I was afraid to leave. What if they didn’t let me go? What if they saw me as an outsider, a witness to their crime?

I needn’t have worried. My friend in drag pointed to me and reminded his peers, “This guy’s on the clock. He’s gotta go.”

All the men shook my sore hand and a few slugged me on my sore shoulders. They were dirty, sweaty, rough-looking gangsters, but okay guys.

My guide and I retraced our steps over the trail to the lot. We halted once to allow a hunching bobcat to scurry past, a fresh-killed rabbit in its mouth. Barred owls swooped down, capturing rodents in the tall prairie grass. The hooting of great horned owls, their deadliest enemies, was seriously creepy.

When we arrived back at the well-lit parking area I still felt nervous. I headed for the SUV, hoping my new mobster pal wouldn’t shoot me in the back before I reached the safety it offered.

He didn’t. He did call out to me, however. “Hey! Aren’t you gonna ask me?”

When I turned around, he was standing with his hands on his hips, head cocked to the side. The wig hair shone a brilliant gold in the light of the street-lamp overhead.

Did he want me to ask him who the dead guy was? How he’d died? If they’d murdered him? Why they were allowing me to leave after witnessing what they’d done?

My legs felt weak and I stuttered for a few seconds before he interrupted me.

“I’m transitioning, bro. But it’s early yet. I got a long ways to go.”

All rights reserved © Mickey J Corrigan 2021

The influencer: Linda Hill, founder of Linda’s Book Bag

Linda Hill founded Linda’s Book Bag in February 2015 and has never looked back, rapidly becoming one of the most influential blog-based reviewers in the country.

As to how she built up her huge following, she says:

“I went on to Twitter and followed all the authors I knew, then searched for publicists and publishers. I put out a few reviews and quite soon I was asked to do a blog tour. It just grew from there – people started sending me books and requesting review space on the blog. It snowballed after the lockdowns. During the first one, I was receiving 200 emails a day. It’s even escalated since then – I’ve just been out to meet someone for coffee and when I got back there were seventy-four new messages waiting for me.”

Linda always refuses payment for anything connected with Linda’s Book Bag (she is a guest reviewer for My Weekly and does accept payment for that). She says she doesn’t want to be paid because her aim is not to act as an advertiser: it would compromise her own morality and she would find it distasteful. She does not, however, give bad reviews. “I can’t read everything I’m sent – nine books arrived this week. It’s wonderful to get a book through the post, but that doesn’t mean I’ve promised to praise it. If I read – or start to read – a book I don’t like, I contact the person who sent it to me and say it’s not for me.”

Once she has met or reviewed an author, Linda often keeps in touch with them. “Lots have become friends – I’ve been to their homes and they’ve been to mine. One of the things I most like about the book community – I mean the genuine book community, people who really love books and writing – is how mutually supportive it is.”

She has only had a couple of negative experiences over the past seven years. One author sent her a book to arrange a book tour and she discovered the book had been ‘completely stolen’ from another author. The author ‘disappeared completely’. And sometimes people who contact her are ‘not as polite as they could be’ – they may take it as a given that she will want to read and review their books.

As well as running her blog, Linda is one of the organisers of the Deepings Literary Festival, now in its third year. The original plan was for it to take place every two years, but the 2020 and 2021 events had to be cancelled owing to COVID restrictions. The festival took place this year, so the next one will be in 2024.

“In the first year I was asked to interview Alison Brice. Planning interviews takes much longer than people realise. I spend several hours researching and writing the questions. I write out the whole script – just so I can get it straight in my head, and, for the last festival, in case I went down with COVID, so someone else could take over.”

Asked if she writes herself, Linda says that she has published more than twenty tutor resource books for Hodder Education. She started her working career as an English teacher and then became an Ofsted inspector. She also set up her own business running independent projects – for example, an event in the Millennium Dome. She was in demand straight away. “The first year I went independent, I had ten free days, including weekends.” She has been encouraged to write by others and once entered a competition run by Simon and Schuster that involved writing the first few chapters of a novel. “They said they’d like to see the rest, which didn’t exist, so I wrote 55,000 words in the space of two weeks! Unsurprisingly, their verdict was that it had promise, but it wasn’t for them.” However, although she has a ‘story in her head’, Linda says she has no burning desire to write. She wants to do other things, including the Book Bag and travel. She and her husband Steve are prodigious travellers and have been from “Antarctica to Zambia, Australia to Zimbabwe.”

Linda grew up in Wood Newton, which at the time boasted a pub and a shop and a solitary telephone box. She was a late reader, not learning to read properly until she was eight, when she first acquired a pair of spectacles and realised that “all those black marks on the pages mean something.” Thomas Hardy is her favourite writer from the classics. Among her modern favourites are Carol Lovekin, Chris Whitaker and, for crime, M W Craven, to whom goes the distinction of being the only writer whose entire series of books she has read. She says her tastes in writing are eclectic – she reads most types of fiction, except SF, Fantasy and Horror.

Asked what advice she would give to new authors, Linda says:

“When you’re contacting reviewers or other people on social media, don’t just launch in with ‘Here’s my book; buy it!’ Build up a following by following authors of books similar to your own. Support other authors. Organise a blog tour – it’s like undertaking a physical tour of bookshops. Take part in social media regularly – not necessarily by writing a lot, but by constantly reminding people you are there. Join Facebook groups – the Crime Book Club, Book Connections. Interact with people. Create relationships and build them up. Be brave: approach local libraries and radio stations. Be prepared to put yourself out there – I know this is hard for some authors.”

Her Majesty the Queen Investigates: The Windsor Knot, by S.J. Bennett

As a small offering to the finale of the Platinum Jubilee long weekend, I thought it would be jolly to review this zinger of a book. First published in 2020, the same year as The Thursday Murder Club, the first of Richard Osman’s crime fiction series about OAP sleuths, The Windsor Knot delights with a similar combination of wicked irreverence, compassion and incisiveness and a similar regard for the prowess of the elderly. Is it too fanciful to suggest that these two novels, both published in the first year of lockdown and therefore written before COVID struck, sparkle with a pre-pandemic joy that is only slowly being rekindled in fiction?

The Windsor Knot tells the story of a murder that takes place in 2016 at Windsor Castle after a soirée that the Queen has agreed to host for wealthy Russians to please Prince Charles, who is hoping for donations to one of his charities. Some of the guests are invited to stay the night and the following morning one of the performers, a young dancer with whom the Queen herself has danced, is found hanged in a cupboard. At first, he seems to have accidentally suffocated whilst engaging in an arcane sexual practice – Bennett has a lot of fun depicting a scene between the Queen and her private secretary in which the latter tries to explain the nature of this practice while cloaking it with a delicate vagueness that immediately causes the Queen to probe further: as she later remarks with terse precision to Prince Philip – who has just observed that the young dancer had been ‘strung up like a Tory MP’ – the official cause of death was ‘autoerotic asphyxiation’. She had looked it up on her iPad.

The Queen, however, comes to realise the accidental death notion won’t wash. Reluctantly she accepts that the young Russian has been murdered and then, with increasing enthusiasm, sets out to uncover the killer. I won’t reveal any more of the plot, as it would be certain to introduce some spoilers; but suffice it to say that at every twist and turn she displays a commonsense attitude coupled with uncanny acumen and impressive levels of expertise in all sorts of areas that perfectly reflect what the actual Queen allows to be known of her character.

As well as trying to shield her from the seamy side of life, people with whom the Queen comes into contact regularly patronise her. She accepts this behaviour with a grace and wry amusement that is shared with the reader. Here she is with Gavin Humphreys, the new Director General of MI5:

She stopped in her tracks, calling briefly to the dogs, who were keen to keep going. ‘Assassination?’ she repeated. ‘That seems unlikely.’

‘Oh, no at all,’ Humphreys said, with an indulgent smile. ‘You underestimate President Putin.’

The Queen considered that she did not underestimate President Putin, thank you very much, and resented being told she did. ‘Do explain.’

There are several prescient accounts of geopolitical events that had not occurred when the book was written but have happened since, the sinister references to Putin included. There are also some scenes that are both funny and sad, particularly those between the Queen and Prince Philip, who in the novel is semi-retired from public life, but still very much alive. About to set off on a trip to Scotland, he asks the Queen if he can bring anything back for her: ‘Fudge? Nicola Sturgeon’s head on a platter?’

‘Actually,’ she said, as he bent arthritically to drop a kiss on her forehead, ‘I wouldn’t mind some fudge.’

Poignantly, the Queen as she appears in The Windsor Knot is ‘only’ eighty-nine and still in robust good health, as the real Queen was at that age. There is now a sharp contrast between this fictional figure and the frail if still beautiful and determined matriarch full of years who appeared so briefly on the balcony of Buckingham Palace last Thursday. The jacket of the book – again, by coincidence – sharpens up the pathos with its illustrations of the Queen’s familiar black handbag, the Queen herself dressed in powder blue, a brooch pinned high on her chest, in an outfit very similar to the one she was wearing last week.

This is a brilliant novel: it sends up the establishment, but only very gently, it offers huge laugh-aloud entertainment, it’s a great whodunnit and, for those who care to look for them, it offers some profound insights into Britishness and what makes the British nations tick. It sparkles with wit but most decidedly is not ‘cosy crime’ – a term I abhor and which is used far too loosely to pigeonhole a work of crime fiction that is not filled with gore and violence on every page. It is crime fiction for grown-ups. I had never encountered S.J. Bennett’s work before I bought this book. The blurb tells us that she ‘wrote several award-winning books for teenagers before turning to adult mysteries.’ I understand that there are already three titles in the Her Majesty the Queen Investigates series. I shall certainly read the others. I hope the real Queen knows about them and has found time to read them, too, as they would certainly make her laugh.