Chaos and casual brutality in Leeds…

A book that I dip into occasionally is Murderous Leeds, by John J. Eddleston. Subtitled The executed of the Twentieth Century, it is a volume of short case studies, sourced from newspapers and court reports, of the trials of people convicted of murder in the first half of the twentieth century in Leeds.

Some of the murders were horrifically brutal; some were pathetic. The extreme poverty of most of those convicted was usually one of the most significant factors in their turning to crime. Many of these people – most were men, but some of the stories are about women – were of no fixed abode and drifted from one tawdry lodging-house to another or picked up women – or men – who were prepared to take them home. Some of the women paid for their generosity with their lives. Yet most of the convicted had jobs of some kind. It is hard to believe that, just two generations ago, many working men could not earn enough money to pay for a roof over their heads.

The saddest of all the stories is the first. It tells how, in 1900, a man called Thomas Mellor, aged 29, killed his two small daughters because he no longer had the means to support them. The jury that found him guilty commended him for his kindness in rescuing them from destitution in this way. He still paid for the crime with his life.

Among the most horrific tales is that of William Horsely Wardell, who persuaded a woman called Elizabeth Reaney to give him shelter and then brutally battered her to death. Attracted by the small reward on offer, her neighbours fell over themselves to ‘shop’ him.

Some of the accounts are bizarre, some are almost funny and a few exhibit a certain amount of intelligence on the part of the perpetrator. Most, however, portray a depressing picture of the grubby chaos and casual brutality of everyday urban working-class life. Many of the murders were not planned, but the result of drunken arguments, some of them ‘domestics’. The banality of these stories is one of the two reasons why I only dip into the book; I still have not read it all the way through. The other reason is that the author has decided to rely on verbatim accounts given by witnesses and judges’ summings-up. Whilst this is in many ways commendable – a treasure trove of fact of this kind is invaluable to a crime fiction writer – it has the drawback of resulting in a certain sameness if more than two or three of the stories are read in one go.

I do plan to tackle the book in one sitting at some point, though, because, as it spans the period 1900 – 1961, I know that a careful reading of it will show me how police methods improved during that time. It strikes me that, in 1900, real villains (as opposed to the desperate and probably mentally ill Thomas Mellor) could get away with almost anything; on the other hand, the forensic evidence produced in court in 1961 in order to convict Zsiga Pankotia, a Hungarian, of the murder of prosperous market trader Eli Myers was very sophisticated indeed.

When I’m walking through the streets of Leeds, especially in the market area, it often strikes me that the people I see may be the children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of some of the victims whose fates are described in this book. Some may even be the descendants of their murderers. Sixty-seven people were hanged in Armley Gaol in the sixty-one years that the book covers. Apart from the exotically-named Pankotia and one Wilhelm Lubina (executed in 1954), almost all of them had good, sturdy Yorkshire names. I do hope that their descendants enjoy a more privileged existence than they did.

In love with Cromer…

It seems fitting to write about Cromer on World Poetry Day. If you are new to the blog, please don’t be baffled by this! Regular readers will know that Cromer is the adopted home of Salt Publishing, which is becoming ever more renowned for its fiction. Last year it achieved international fame with The Lighthouse, Alison Moore’s debut novel, which was shortlisted for the 2012 Man Booker prize. (Its crime list includes In the Family, my first crime novel, and will shortly also feature Almost Love, the second in the DI Yates series.)

However, Salt built its reputation for literary excellence on its superb poetry list; in my view it is the greatest current British publisher of contemporary poetry. Some Salt poets are poets’ poets, though most are very accessible. I believe that perhaps, of all its achievements, Salt’s greatest has been to develop its ‘Best of’ lists, especially the Best of British Poetry series, and the Salt Book of Younger Poets. Now widely adopted by undergraduate courses in English literature and creative writing, these books bring contemporary poetry alive to a new generation, as well as supply more mature readers with an impeccable selection of great poems. The Best of British Short Stories series achieves a similar effect in a different genre. And, not to spare his blushes, Chris Emery, the founding inspiration behind Salt, now publishes his own poetry under the Salt imprint. If you have not yet read The Departure, I recommend it wholeheartedly.

Back to Cromer. I was there for a long weekend because, as I mentioned on Sunday, I was asked to play a small part in the Breckland Book Festival. I stayed at The Barn, one of the cottages owned by The Grove Hotel (itself steeped in history – parts of it are eighteenth-century and its original owners were the founders of Barclays Bank). I called in on Chris and Jen Hamilton-Emery after the Breckland event and my husband and I were kindly invited to have dinner with them. They were brimful of ideas as usual and delighted that Chris has been appointed writer-in-residence at Roehampton University, as well as looking forward to celebrating Jen’s birthday today (that it is on World Poetry day is a poetic thing in itself!).

The rest of our time in Cromer was spent exploring the beaches and the streets of the town. Twice we walked along the beach in the dark and, on Monday morning, we took our dog for a very early morning run there. Even in bitterly cold weather, the town itself is enchanting. Developed in the mid-nineteenth century to cater for the emerging middle classes, who could for the first time afford holidays away from home, it seems to have been preserved intact from any attempted depredations by the twentieth century. There are not even many Second World War fortifications in evidence, though a pill-box languishes in the sand of the west beach, its cliff-top site long since eaten by the sea. The pier retains its pristine Victorian originality – it is well-maintained but has not been ‘improved’. Some of the hotels, again ‘unreconstructed’, are quite grand and all serve superb food at reasonable prices, as do the many cafés and restaurants. It is true that some of the shops seem to exist in a time warp. My favourite is the ladies’ underwear shop that does not appear to stock anything designed after 1950; it even displays ‘directoire’ knickers – much favoured by my grandmother – in one of its windows.

Cromer has a literary past, too. Winston Churchill stayed there as a boy and Elizabeth Gaskell was a visitor, as the pavement of the seafront testifies. (Churchill apparently wrote to a friend: ‘I am not enjoying myself very much.’) That Tennyson also came here, even if I had not already decided that I loved it, alone would have served to set my final stamp of approval upon the town: Lincolnshire’s greatest poet, he is also one of my favourites. (I’ve always considered James Joyce’s ‘LawnTennyson’ jibe to be undeserved.) I know that Tennyson would have been fascinated by Salt if he had been able to visit Cromer today. I can picture him perfectly, sitting in Chris’ and Jen’s Victorian front room, sharing his thoughts about poetry – as one fine poet to another – in his wonderfully gruff, unashamedly Lincolnshire voice.

And so, Jen, Chris and Salt, have a very happy Cromer day, listening to the lulling rhythm of the rolling, scouring waves and painting salty pictures in the sky.

A brief encounter with Brighton… and a book

Last week I visited Brighton for the first time in perhaps ten years. I was there because The Old Ship Hotel had been chosen as the venue for the annual academic bookselling and publishing conference for which I organise the speaker programme. I discovered that there has been an inn on the site of The Old Ship since Elizabethan times. Originally just called The Ship, it acquired its venerable epithet after another Ship hotel was built nearby – this one a mere stripling dating from the period of the Civil War. Hotels in Brighton can be evocative places. I have also stayed at The Grand, both before and after it was wrecked by the IRA bomb, on both occasions to attend the Booksellers Association Conference (I liked it better before than after) and one year spent several days in a seedy little guest house when the company I was working for forgot to book until the last minute and all the hotels were full.

Brighton itself has not changed much in ten years, although it looked very odd when I arrived, because the streets and seafront were covered in grubby snow. A moderately heavy snowfall on the day before seemed to have caused a local catastrophe in which everything – public transport, the highways, even restaurants and cafés – ground to a halt. I concluded that they’re ‘nesh’ in the South of England; we clear away snow like that in half an hour in Yorkshire! Or perhaps Brightonians – if that’s the right word – are just staggered to see the white stuff at all and it therefore strikes them down with a sort of horrified inertia.

Anyway, by midday, although it was still very cold, the snow had melted and I ventured out from The Old Ship to meet my former English teacher for lunch (more about this on another occasion). Before the conference started, I also managed to take a walk along the promenade and was saddened to see the hideous buckled corpse of the West Pier, still rising up out of the sea like a squashed daddy longlegs. The structure has suffered terminal damage since my last visit.

After presentations, drinks and speeches, dinner, more speeches and more drinks, I went to bed. I was rudely awakened at about 4 a.m. by the noise of a huge crowd outside. I exaggerate only a little when I say that it sounded like the storming of the Bastille! I began to realise that my de luxe room, with its fine view of the sea, came with mixed privileges. Looking discreetly out of the window, I saw a gang of perhaps forty youths running about on the seafront, many of them braying obscenities. And they didn’t move on – they just stayed there! Brighton has obviously degenerated since the days of Pinkie Brown, who was a better class of yob altogether.

Since it was obvious that I would get no more sleep until the mob dispersed or was moved on, I adopted my usual all-purpose tactic for dealing with adversity and took out a book. It was The Mistress of Alderley by Robert Barnard, not a novelist I’d read before. Under normal circumstances, it wasn’t the sort of novel I’d have especially enjoyed. Although the setting is meant to be contemporary, the characters seem to belong to a time warp. The mistress of Alderley herself, a retired actress called Caroline Fawley, seems to me to be straight out of the set of Brief Encounter. However, under any circumstances I should have enjoyed the detailed descriptions of Leeds which number among the novel’s strengths and, while the fracas outside continued to roar, I found the descriptions of Caroline’s genteel rural life quite soothing. The icing on the cake was that it turned out to be a sham, a pretence laid bare by the murder of Caroline’s slippery millionaire lover.

I had almost completed The Mistress of Alderley by breakfast, by which time the louts had melted away and a rosy dawn was launching itself above the dead pier.

Elly Griffiths and Tom Benn in fine form at Breckland!

The small Norfolk town of Watton yesterday afternoon braced itself for bleak and squally weather, the rain coming in short eddies between gusts of wind that made the temperature seem even colder than it was. Inside, the library was a haven of warmth and hospitality, as Claire Sharland and her colleagues put the finishing touches to the Breckland Book Festival crime-writing event and offered welcoming cups of tea.

Elly Griffiths, Tom Benn and I all arrived early, as requested, and gathered in a small office to introduce ourselves and get to know each other a little better before we were ‘on’. I was fascinated to discover that Elly also writes novels about the Italian ex-pat community as Domenica de Rosa, her fabulous real name, and that Tom was encouraged to publish by his tutor at UEA, who helped him to place his first novel, The Doll Princess, with Jonathan Cape.

When we emerged from the small office at 3 p.m., the events space in the library had filled completely with people. I estimate that there were about forty in the audience – an impressive turn-out on such a dismal day.

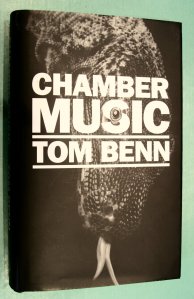

Tom and Elly both read from their latest novels. Tom made the distinctive Mancunian dialect in which he writes come alive with his reading and, by doing so, also brought out the sophisticated humour which runs like a fine thread through the whole of Chamber Music. Elly also chose a humorous piece of dialogue from Dying Fall, and made the audience laugh with her vivacious rendering.

We were fortunate to have such a receptive and intelligent audience. Most had read the work of one of the authors; some had read both. Their comments and questions took in a discussion about the two writers’ very different but, in each case, key use of topography, character development, how each uses his or her writing to explore and develop relationships and the extent to which they feel defined by belonging to the crime writing genre (they don’t). We even managed to get on to some more general topics, such as e-books, authors’ royalties and the Net Book Agreement (the latter introduced, not by me, but by a member of the audience who had been a bookseller in the distinguished Waterstones bookshop at UEA).

Time flew in the company of Elly and Tom and their audience of like-minded lovers of literature. I had not read either Elly’s or Tom’s books before, but shall certainly keep them in my sights from now on. I hope also that we shall meet again in the future.

I can’t conclude without adding that the tea and home-made cakes with which we were rewarded at the start of the signing session were excellent. I’ve discovered that cake and conversation are two things that Norfolk does very well indeed!

Putting a person to a name… Waterstones Gower Street

As readers of this blog have often kindly expressed an interest in my books, I thought you might like to know that an event has generously been organised for me by Sam, the wonderful Events Manager at Waterstones Gower Street, on Thursday 21st March 2013. It will start at 6.30 p.m. and last for perhaps an hour. I shall be reading a short excerpt from In the Family and perhaps also one from Almost Love (which will be published in June), and offering a few tips, from a personal perspective, on how to get published. After this, there will be a short Q & A – and a glass of wine! The event is a sort of forerunner of a larger Salt crime event that will be hosted by Gower Street on 23rd May 2013.

I know that readers of the blog are scattered far and wide and that some of you don’t live in Europe. Wherever you are, I am very grateful to you for your interest and have been delighted to ‘meet’ you on these pages. For those of you who happen to be in London next Thursday or can travel there easily (and would like to, of course!), I should be delighted to have the opportunity to meet you in person.

Chamber Music, a novel for Breckland Festival

Chamber Music, by Tom Benn, is not the sort of book I’d ever pick out for myself in a bookshop, given a free choice. Why? Because even though I am impressed by the skill of writing a dialect-heavy novel, I find such an approach to dialogue rather painful to read; also, when I’m not very familiar with the dialect, I can’t ‘hear it in my head’. I must admit, too, that the presentation of the seamier side of life for a whole novel is, for me, too much noir in one go! However, as I’ve explained in a recent blog-post, I’m meeting Tom at a Breckland Book Festival crime-writers’ session which I’m chairing. Claire Sharland, the organiser, kindly offered to pay for this book if I acquired it. I should add, hastily, that of course I’d have made sure that I’d read it before meeting Tom, in any case!

Technically speaking, it is a brilliant novel. I don’t quite know how to describe the technique that Tom has used – it is Irving Welsh crossed with William Faulkner, if that makes sense. I know that often writers resent being asked if their books are autobiographical or ‘drawn from life’; and, whilst I have no intention of asking Tom such a question, it seems likely to me that he must have lived and breathed the under-class, criminal-underworld Mancunian society that he depicts – otherwise he would never have been able to write such pitch-perfect dialect or captured the topography of the mean streets of Manchester with such conviction. On occasion, the use of dialect is so rich that the non-Mancunian reader is baffled, but such is Benn’s skill that eventually it is possible to decipher meaning from context. For a simple example, I picked up quite quickly that ‘scran’ is slang for a tasty snack.

This book has very little in common with Elly Griffiths’s Dying Fall, the other book featured in the Breckland session, which is no doubt why these two authors were billed together. However, both do share a pronounced sense of place and in both novels I feel that the crimes act as a vehicle for exploring the characters, rather than themselves being the focal points of the novels. Henry Bane is a complex character who takes a lot of fathoming – I suspect I should learn even more about him if I were to read the book twice; and Roisin is portrayed in an enigmatic and, given the situations in which she is placed, paradoxically delicate way.

I’m particularly looking forward to asking Tom Benn to read a passage from Chamber Music when I meet him next Saturday, for I want to get the authenticity of his voice into my reading of the novel; I’m sure that a live reading will be captivating.

Cake, coffee and crime, a killer combination in The British Library

Yesterday, London was in the grip of one of those gloomy, fog-bound days of which Dickens wrote so eloquently. The streets were grey and obscured by swirling mists so heavy that they fell like grubby rain on clothes and hair. People were scurrying about, heads down, doing damage with their umbrellas.

The British Library shone, as always, an oasis of light, heat, calm and coffee… and, importantly, cakes. I went to the café there to meet a colleague and, our business done in ten minutes, we had a wonderful time drinking in the power of George III’s magnificent book collection (which is displayed behind glass and occupies the full height of the building) while eating chocolate pastries.

My colleague had to leave at midday, which gave me an hour to kill before my next meeting. This was just as I had planned, because I had picked up from Twitter that a Crime Writing exhibition is currently on display there.

Sponsored by the Folio Society (which has apparently published quite a lot in the genre, a point to remember when trawling secondhand bookshops for old Folio Society titles), the exhibition takes an alphabetical approach to crime writing. It consists of twenty-six glass showcases, one for each letter of the alphabet, each one showing or explaining some aspect of the crime writer’s craft. Unsurprisingly, ‘A’ is for Agatha Christie; ‘Z’, less obviously, for ‘Zodiac’ – i.e. for crime writing based on the occult.

It is an inspired way of celebrating the genre. My favourite letters included ‘L’ for lady crime writers – I had not realised that until P.D. James published her debut crime novel, Cover her Face, in 1962, the fictional lady sleuth had pretty much dropped out of sight since Victorian times – and, of course, ‘B’ for Baker Street. The Holmes showcase included some specimens of Conan Doyle’s manuscripts (which I photographed before I was told to put away my camera by a security guard – I honestly had not realised that photography was not allowed!). I revisited many crime-related topics that I’ve researched myself, often presented in ways that made me regard them anew, and discovered some fascinating facts; for example, that Wilkie Collins’ estimated annual income from The Woman in White (published in 1860) was £60,000 p.a.

This equates to about £4.5m today. It and many of the other exhibits served to prove that, right from the start of its inception as a genre, crime writing could be made to pay. The exhibition, which is free, takes about half an hour to absorb. I highly recommend a visit if you get the opportunity – especially if it is raining and you are struck down by a pressing need for coffee… and cake.

My favourite bookshop!

Yesterday I visited Waterstone’s Gower Street, which in my mind is called simply ‘Gower Street’ and, in many other people’s, is still indelibly fixed as ‘Dillons’. A great bookshop and, of all the bookshops I have visited (there have been a few), easily my favourite. It’s situated in the heart of Bloomsbury. Approaching from Gordon Square, you come upon it suddenly, an Arts and Crafts enchanted castle before which there is always a litter of student bicycles, as if thrown down in homage at its feet. On an early spring day, especially when the sun is shining, your heart lifts immediately.

The shop was founded by Una Dillon, herself one of the extended ‘Bloomsbury set’. Almost every other door of the houses in Gordon Square and adjoining Fitzroy Square is adorned with a blue plaque celebrating the fact that a Bloomsbury author lived there; Una Dillon created the shop to serve them. The building was originally an early experiment in franchise retailing, a sort of forerunner of the Galeries Lafayette or Selfridges. It was designed to house twenty-four retail units, one of which was initially taken by Una Dillon. Gradually, over a period of years, she expanded until she had bought all of the units and therefore the whole building. (This also lifts my heart: I wonder if there is the remotest possibility that this could still happen today? Could a bookshop oust, say, Zara, Boots, Gap, Marks & Spencer and their ilk from such an ‘emporium’? I have my doubts!) Consequently, behind the scenes, it is a rabbit warren of corridors and small offices. It is also a protected building – of which I’m entirely in favour – although it does mean that not even a nail can be knocked into the wall without English Heritage’s being first consulted.

This shop came under my jurisdiction for several years in the 1990s. At the time, there were booksellers there who could remember Una Dillon’s being wheeled into staff meetings in her wheelchair and who were still in awe of her memory. (I must admit that the image of this is conflated in my mind, unfairly I’m sure, with the image of Jeremy Bentham’s stuffed corpse, similarly wheeled into meetings at UCL nearby, but I’m sure that Una was still alive on the occasions of which they spoke!)

I myself have many excellent memories connected with the shop – for example: the launch for George Soros’s book, which attracted so many people that it had to be held in a lecture theatre at UCL, with a television link to an overspill room; coming out of the manager’s office and finding Will Self chatting to the staff in the reception area; walking back a little dazed to King’s Cross through a summer dawn on a Sunday morning, having – with all of the staff – been up all night stocktaking. And it is still my favourite place for browsing and buying books.

Great bookshops are like people – they have personalities. A great old bookshop like Gower Street also has secrets. As far as I know, there has never been a murder committed there, but there could have been. Maybe someone will write a novel about it!

How creative a fertile imagination, given the opportunity!

Some time ago I wrote about Moon, the chef in the Chinese restaurant where I worked as a student, and how I was convinced that he had it in him to be a latter-day Jack the Ripper.

The summer when Moon and I worked together preceded the so-called ‘Yorkshire Ripper’ era, though there is some evidence that Peter Sutcliffe may already have begun his attacks by then. By the time that I was married and living in a semi-detached house in Leeds, at least twenty women had been injured or murdered by what was believed to be a single perpetrator, and the Ripper investigation was in full swing. During the last few years before Sutcliffe was caught, some of his victims were no longer prostitutes and all women living in Yorkshire were warned not to be out alone in the streets during the evening or in the early hours of the morning. We were even advised not to take the rubbish out after dark. Naturally, this both terrified us and had a substantial effect on the way that we organised our lives. For example, my husband drove me fourteen miles to work every day and came to pick me up in the evening so that I should not have to linger at bus stops or railway stations by myself.

After ‘Wearside Jack’ had played his silly pranks (He sent tapes to the police claiming to be the Ripper, speaking in a strong Geordie accent; it was not until 2006 that he was finally brought to justice.), members of the public were advised to be especially vigilant if they saw anyone acting suspiciously who also spoke Geordie. Our next-door neighbour worked for the Ministry of Defence at Barnbow in Leeds. He was a very shy man in early middle age who hardly ever spoke. He had a large family, but seemed to spend very little time with them. Most evenings and weekends he would hide himself away in a large shed that had been erected between his house and ours. And, when he did speak, it was with a Geordie accent.

My husband and I, who, like almost everyone else we knew, were obsessed with the Ripper case, discussed this neighbour energetically on several occasions and, before too long, had convinced ourselves that he was a likely Ripper candidate. We dithered about what to do about this: after all, we had no evidence to go on besides his accent and his general shiftiness. The police would probably laugh at us and, in any case, we didn’t want to cause trouble for him if he was innocent. Consequently – and fortunately, as it turned out – we had taken no action at all when Sutcliffe was finally apprehended. (Despite having ourselves read and listened to all the Ripper news bulletins for years, it was a friend who lived in King’s Lynn and had seen it on the TV news who rang to tell us that he had been caught.)

Our neighbour continued with his mysterious shed-based life. One day, after our son was old enough to play outside, he was invited into the shed. He told us that the neighbour had built an elaborate radio station in there and was in touch with people all over the world. He had let our son listen to some conversations that he’d had with his contacts in Russia and China.

He was still living next door, still devoting himself to life in the shed, when we moved away from the area. Obviously he turned out not to have been the Yorkshire Ripper. Nevertheless, with hindsight and perhaps a touch of imagination, I wonder if he was just an innocent radio ham, or whether his ‘hobby’ concealed a more sinister purpose. He was, after all, an MOD engineer…

Fabulous: a book festival!

I am delighted to have been asked to chair the crime writers’ event (at Watton Library in Norfolk), which takes place as part of the Breckland Book Festival on Saturday 16th March. It’s a session that features Tom Benn and Elly Griffiths.

Yesterday Claire Sharland, one of the organisers of the event, got in touch to suggest that I should read their latest novels, Chamber Music (Tom) and Dying Fall (Elly), before the session and generously added that the festival would pay me for the purchases. I am delighted with this offer – I shall buy the books when I am in London next week. I’m sure that, very shortly, I shall also be reviewing them on this blog!

It’s always nice to be given some books, especially if you buy them all the time. I’ve long been amused by the Booksellers Association’s definition of a ‘heavy book buyer’ as someone who buys twelve or more books a year – most years, I barely get through January without hitting this figure. What really excites me, however, is that someone has prescribed my reading for me. I’m going into this totally blind – I haven’t been prompted by reviews, word-of-mouth recommendations or even by spotting the titles in a bookshop. Aside from examination texts, I can’t remember when I was last instructed in what to read in this way. It might have been during my third year at high school, when the class text was My Family and Other Animals, by Gerald Durrell. My bookish, priggish thirteen-year-old self turned up her nose in disdain when sets of this were distributed. I didn’t think it was suitable ‘serious’ reading for someone who, while still at primary school, had read such classics as Jane Eyre, The Thirty-Nine Steps and Great Expectations, especially as – distasteful innovation – the school copies were in paperback!

It’s a pity that I didn’t adopt such a fastidious approach to every subject. Today I wouldn’t be able to recognise a quadratic equation if it bopped me on the nose; and I’ve never mastered the mysteries of algebra (though it now occurs to me that it could be a useful vehicle for plot construction: let x be the murderer, y the victim, z the wicked stepmother etc.).

I should add that my precious teenage prejudice against My Family was immediately dissipated by reading its delights; I’ve read it several times since and it was one of the books that I read to my young son at bedtime. I’m certain that I shall like Tom’s and Elly’s novels, too, and look forward to making their acquaintance, first through their work and secondly in person. If anyone reading this should happen to be in the vicinity of Watton Library at 3 p.m. on 16th March, I hope perhaps to meet you there, too.