“I’ve been a wild rover for many a year, and spent all my money on bleep and bleep…”

The crazy topics for which researchers are awarded grants are often a source of great amusement to me. During the past year I’ve read about a project that, after many months of expensive labour, ‘successfully’ created a formula for the ‘ideal’ slice of toast and marmalade (it wouldn’t succeed in our household, where some of us like our toast burnt and others don’t); a study that ‘proved’ that there is a link between depression and being unhappy at work; and, just this week, a piece of research that shows that the pop songs of today contain twice as many references to alcohol as the ones of twenty years ago.

At first I thought that the last of these was very funny indeed. Good on the researchers who have persuaded whomever awarded their grant that it would be a good use of scarce resources to pay them to sit around endlessly listening to pop music. More power to their (drinking?) elbow. But now I’ve had time to consider, I’ve begun to wonder if there isn’t something more sinister afoot here. Assuming that this study is not entirely mindless and redundant, to what use is it intended to be put? Is the government going to start censoring pop songs? If so, it would very decidedly be the thin end of the wedge. It’s not just about pop music: from the earliest times, alcohol has been a part of almost all cultures, as is reflected in their art and literature. Just imagine what would happen if a Nahum Tate style of censorship were to be applied to books. Offending works would have to be covered in brown paper, and an approximation of their titles offered instead:

• Tizer with Rosie, by Laurie Lee

• Irn Bru Galore, by Compton Mackenzie

• Cakes and Tea, by Somerset Maugham

• Dandelion Juice, by Ray Bradbury

However, having to alter the titles would be a mere bagatelle compared to the changes that would have to be made to the works themselves. Homer’s ‘wine-dark sea’, almost his trademark description, would have to become the ‘grape-juice dark sea’; Lady Macbeth would have been stuffed if, instead of being able to observe, as the grooms slipped into a drunken stupor, ‘that which hath made them drunk hath made me bold’, they’d all been swigging elderflower water and sitting up playing cards, as lively as crickets; and ‘wine, women and song’ (which I’ve just looked up, and find, to my amazement, that it is a saying usually attributed to Martin Luther) would not have the same ring to it if it became ‘water, women and song’.

I jest, but I am also being serious. This type of statistical analysis is not only nonsense, but also very dangerous. Cultures cannot be manipulated, and even if this particular statistic is true, it doesn’t necessarily mean that society is becoming more decadent. One interpretation might be that, at present, writers of pop songs are going through a very literal phase, which may mean that there are fewer double entendres to pick up on and correspondingly more overt references to be spotted by the earnest conductors of surveys. The pop songs of my youth were full of allusions to drugs, drinks and sex, but many of these were disguised. I wonder if present-day researchers would have spotted them? Self-evidently, also, my generation survived and turned out to be no more or less decadent than any other. Culture must be allowed to regulate itself.

If the government interferes in this, you may find me in my local singeasy.

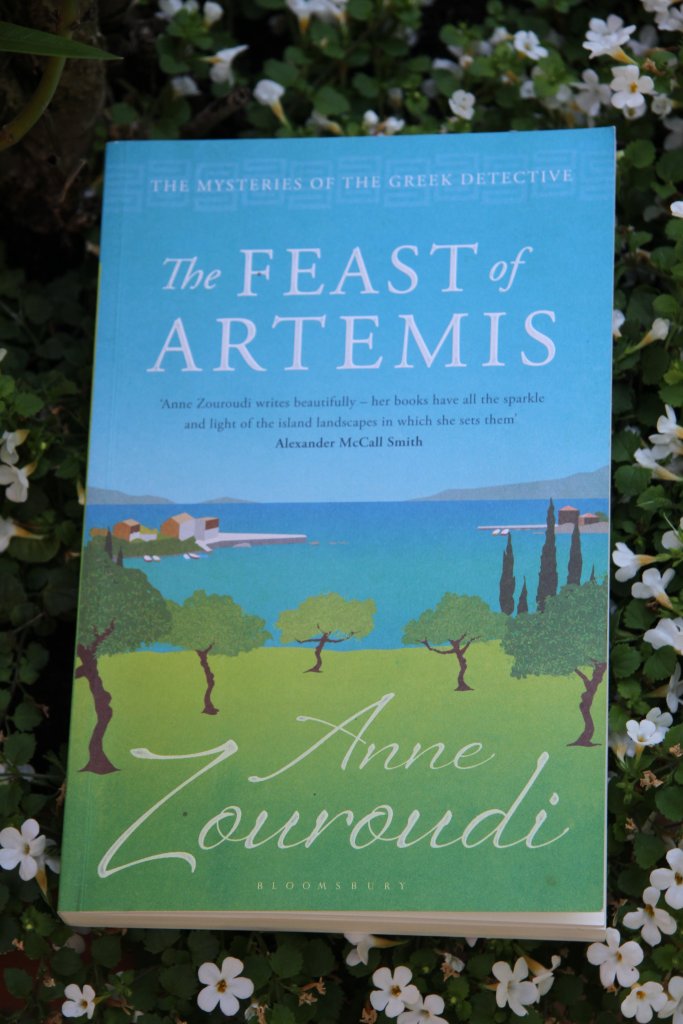

The idyll and the agony, with Anne Zouroudi (@annezouroudi) …

The Feast of Artemis is the seventh novel that Anne Zouroudi has written about her mysterious amateur detective Hermes Diaktoros. It’s only the second of the series that I’ve read – I completed The Messenger of Athens last year, shortly after hearing Zouroudi speak at a crime writers’ evening held at the offices of Bloomsbury, her publisher – so I now have the very great pleasure of being able to look forward to devouring the other five. I shall buy them as soon as I can.

I find the quality of Zouroudi’s writing almost haunting. It is classic in that it belongs to the oldest European literary tradition of all, that which has Homer himself sitting at its head. I’ve written elsewhere about how Zouroudi’s intensely poetical yet austerely precise descriptions of the Greek landscape remind me of Homer’s own accounts of the Greek islands in The Odyssey, which, more than two millennia after they were conceived, still amaze with their freshness. The Feast of Artemis also contains such evocative passages, but Zouroudi – always reinventing herself within the universe that she has created – in this novel focuses especially on describing food. The clue, though, is in the title: as the reader is aware, Artemis is the feisty goddess of hunting; in Greek mythology, she at various times exacts retribution, and in the novel terrible things are done in her name, some with unforeseen and unintended consequences.

Just as beneath this glittering, sun-drenched paradise lives the peasant community of Dendra, whose members are tarnished with all the human vices, so concealed within their sumptuous festive meals lurk danger and destruction. Food is both the bringer of life and the harbinger of death in this novel. The finely-drawn characters, whilst naturally displaying none of the urbanity of Diaktoros himself, show both cunning and a taste for revenge that matches that of the gods of old.

The central plot concerns a generations-long feud between two olive-growing families. A cycle of vengeance and retaliation results in the death of the patriarch of one of these families and the mutilation by fire of a youth from the other. One of the book’s many masterly touches consists of a kind of tightening of the screw as the plot unfolds: we are told early on that the youth has been burnt, but the full significance of this is not revealed until the closing stages. The small clouds that hover over the sunny landscape right from the beginning grow darker as the novel progresses and the effects of evil are revealed.

Yet such is the author’s subtlety that none of the characters in The Feast of Artemis is evil through and through. The publisher has placed it within the crime genre, probably correctly, but it belongs to that relatively small group of distinguished crime novels that can be read on more than one level. Fundamentally, it is a book about the human condition. Although Hermes was the messenger of the gods, and Hermes Diaktoros, in his guise as moral arbiter, shares some of his namesake’s characteristics, he is also a modern-day Zeus, swooping down, not in anger, but with a kind of sadly humorous wisdom, as he conducts his inexorable quest to get at the truth and show the perpetrators of the crimes the errors of their ways. That he himself has foibles is a stroke of genius: in a place where life and death are governed by food, he is continually tempted by delicacies that threaten his own well-being because he is already overweight. It also emerges that he is brave to eat some of the food that he is offered, knowing as he already does that those providing it are guilty of introducing poison to their seemingly delicious comestibles. Yet he is nimble on his tennis-shoe-clad feet and has a brain of quicksilver. That he is not perfect lends authority to his perspicacity and ensures that it is not marred by overt moralising. Another fine touch is the introduction of his brother Dino, who is as much a slave to wine as Hermes is to food: Dino – the echo of the name is surely intentional – plays Dionysius to his Zeus. (I’m not sure whether Dino also appears in some of the five novels that I haven’t yet read: my guess is that this is not his first appearance in Zouroudi’s oeuvre.)

At the end of the book, resolution is achieved, but at a price. Peace is brought to the community of Dendra, but it is made clear that its inhabitants will continue to bear the scars – and in some cases, to pay custodial penalties – for their wrongdoing. Hermes Diaktoros himself, having arranged to pay for the best plastic surgery that money can buy for the damaged youth from his own seemingly bottomless yet inexplicably acquired funds, simply melts away. God’s in his heaven, all’s right with the world – until, we hope, the next time that his intervention is required.

If you haven’t yet read Anne Zouroudi, you should; you will find her compelling command of the Greek ‘idyll’ as stuffed with flavour and irony as the roasted lamb from the fire pits of her opening chapters in this book.

On a beautiful day, an exquisite work…

I apologise to regular readers – and I should like to say here that I am extremely grateful to you for being regular readers – of this blog, for presenting you with a book review two days running. Perhaps as an antidote to my dose of Sheridan Le Fanu (whose works, whatever their good qualities may be, certainly belong to Henry James’ category of ‘loose baggy monsters’), I began last night to read The Cellist of Sarajevo, by Steven Galloway, and did not put it down until I had finished it.

It is a breathtakingly beautiful novel, although it deals with that ugliest of subjects, civil war. It is also very grown-up, with profound layers of meaning that are allowed to speak for themselves; the author does not intrude upon the reader by presenting any kind of moralistic commentary.

At the literal level, the story consists of a portrait of the horrors of the siege of Sarajevo as seen through the eyes of three people over the period of a few days. Fundamentally, the novel is an examination of what it means to be human and what ‘being good’ really consists of. Principles of right and wrong are explored both through the most extreme situations (for example, Arrow, the female sniper working on behalf of the townspeople, finds it increasingly difficult to justify her acts of killing the ‘men of the hills’, even though they are picking off her fellow citizens daily) and more mundane dilemmas, such as that of Kenan, who, when he risks his life to collect water for his family, resents also having to fill up two heavy and awkward water containers for his elderly neighbour, not because he likes her (he doesn’t) or because she has been kind to him (she hasn’t), but because she holds him to a casual promise of help made in happier times.

The cellist is the common thread that unites these characters, as they listen to him; they do not know each other and do not meet. The reader discovers little about him. He is a roughly-dressed, unkempt man with no name who has taken a vow to play his cello every day for twenty-two days in a street where twenty-two people died as the result of a mortar attack. Daily, therefore, he puts himself at risk of murder by one of the snipers in the hills. He is an enigmatic, Christ-like figure. Did he lose someone in the mortar attack or is he making a point about preserving art and maintaining civilised activity in a world grown savagely feral and full of fear? Does he celebrate or mourn humanity?

Almost every sentence that Steven Galloway writes delights with its precision and eloquence. My guess is that he rewrote some of them many times in order to convey the exact descriptions, meaning, undertones and overtones that he intended. However, nowhere is the novel ‘overwritten’.

I believe that this is a very important novel indeed; it belongs to the literary tradition of writing about the juxtaposition of warfare and what it means to be human that stretches back through Tolstoy and Shakespeare to the Icelandic sagas, Virgil and Homer. It is elegiac, timeless and yet very disturbingly modern.