To Brighton again, with spring in step…

As you can tell from the date of the picture I took from the train window just over a week ago, this post is a little behindhand. I was then, and am now, heading south on East Coast rail. What a lot has changed in one week! The temperatures have soared, high pressure has established itself over the whole of the UK and the train Wifi is working for once! I’m conference-bound today, with all the lightness of heart that good weather brings. Here’s what I wrote last week:

I’m on the train to London again, for the first time in quite a while. It’s just after 7 a.m. and broad daylight – a luxury that I haven’t experienced on this journey at this time since last October. It’s chilly: the fields are damp, still drying out after the rains, and a low mist rises from the earth as it warms up for the day. The sky is oyster-coloured and fretted with a complex pattern of clouds that seem to form the shape of the skeleton of a whale, or some long-dead prehistoric beast; I see a dog running across the grass, but can’t spot its owner. Mostly the land in this area is flat and arable, but occasional huddles of cows or solitary horses tethered in a paddock, grazing peacefully, flash by.

As usual, there is a problem with the train’s WiFi, but mercifully the electrical sockets are working, so I can still use my laptop. This is just as well, because, try as I might, I’m struggling to find my fellow passengers interesting. Opposite me sits a burly man reading the Metro newspaper. He licks his finger to get a purchase every time he turns the page, an unhygienic habit that I’ve always found irritating (particularly when employed by bank tellers counting out notes that I must then grasp). I wonder how much newsprint he swallows each week? The man sitting opposite is slenderer, younger and quite geeky. He’s wearing square, heavy-framed spectacles and is immersed in his iPad. I can just see that he is reading the Financial Times (and can tell that he is familiar with East Coast – he’s downloaded the paper before getting on the train!). At least there’s not much prospect of his sucking on his thumb and index finger as he scrolls down the articles!

Looking round, I see that all my fellow passengers are men. The ones behind me, each seated at a separate table, are all reading documents and making notes: weekend work that didn’t get done, I guess.

Now the train is approaching Newark Northgate. The sun is riding quite high in the sky, but is still watery and pale. Newark is this train’s last stop before King’s Cross. Quite a crowd of people is waiting to embark, but again not a woman in sight. Smarter than I, perhaps – they’ve managed to stay at home to enjoy what promises to be a bright early spring day.

Breakfast arrives (I’m travelling first class, though on a very cheap ticket, because I ordered it weeks ago). It’s a smoked salmon omelette. Porridge and fruit compote, which was what I really wanted, has apparently ‘sold out’. I’m sceptical about how this could happen on a Monday morning. Someone forgot to fill in an order form, perhaps? The omelette is OK, but the half-bagel on which it sits looks tough and rubbery. I decide to give it a miss.

All of this, I’m sure you’ll agree, is quite humdrum. The journey is one that I’ve made scores of times before, usually, but not always, with more promising travelling companions. (I’m hoping that the rest of it will be as uneventful and that the train will arrive on time, as I have only forty minutes to cross the city to get my connection at Victoria.) But my spirits are lifting. I feel the old magic that I’ve always associated with train journeys since I was a child. It’s been dulled by the dreariness of winter, but today it has returned, in full strength.

It’s 8.10 a.m. and the sunlight is streaming through the train window, flinging a glare of orange across the computer screen so that I can hardly see these words. Spring is here. When I arrive in London, spring will be burgeoning there, too. It is the beginning of March and at last it seems as if the year has really started. There is the whole of the spring to sip at as if it were a delicacy and the almost-certainty that it will be followed by the feast of summer. It will be eight whole months before we shall arrive at the end of October and watch with dismay the withering of the trees and the light as winter approaches again.

Today, I am travelling to London, then on to Eastbourne: an ordinary work-day expedition. But it is part of a much bigger, more exciting journey: my odyssey into 2014.

Today, I am travelling to Brighton, where this year there will be no heaps of snow on the promenade and I’ll be interested to see just how little the storms have left of the West Pier skeleton, which I wrote about and photographed twelve months ago.

Have a lovely week of spring weather, everyone.

Sweet and sour: sugar and our nanny state…

It’s a beautiful spring day and I’m luxuriating in the winter’s departure – though still with a wary eye on the sky, as I’m mindful that this time last year there were hedge-high snowdrifts in the lanes near my house. When I arrived in Brighton in March 2013 for the conference at which I annually organise the speaker programme (and for which I am departing again tomorrow), the promenade was deep in snow and Brighton, that gaudy seaside princess accustomed only to balmy springs and mild winters, had stamped her foot and gone on strike: nothing was operating; not trains, buses or cafés, and the lone taxi driver who had ventured out deposited me at my hotel with all the air of a Himalayan Sherpa supporting a winter expedition. But tomorrow, I’m told, the sun will be shining, the temperatures unusually warm for the time of year.

It’s perhaps a little unseasonal of me, therefore, to embark upon a rant. Rants are normally reserved for foggy November days and chill winter evenings, when the humours are out of sorts and venting one’s chagrin upon the world is, if not de rigeur, then at least condoned. However, I haven’t had a rant for ages, so perhaps may be allowed a little leeway now. It is also unusual for me to comment on political issues, but I’m going to do that, too.

If you read the newspapers regularly, you will have noticed that the government’s latest frenzied preoccupation is with sugar. Yes, sugar. Not tobacco or marijuana or alcohol or ‘hard’ drugs or even prescription drugs, all of which we know to be major killers in the UK, but sugar. The government is considering the imposition of an extra tax on foods and drinks that contain high sugar content – whatever that means (the cynic in me whispers that this might – incidentally, of course – turn out to be a nice little earner). Meantime, the World Health Organisation (THE WHO?!) has suggested that sugar should form no more than 5% of our diet.

Now, I am not a scientist: in fact, if you were to line up twenty random people and assess their ignorance-of-science credentials, I reckon I would get the top slot, or certainly the runner-up’s. Because I needed a science subject in order to get into university, I studied Biology – that traditional ‘soft option’ for arts and languages students – and, after much labour, succeeded in obtaining a moderately respectable grade which was, incidentally, the worst of all my examination results, ever. However, I do remember quite a lot of the information from my ‘O’ Level Biology course, having managed to din it into myself by rote, and since then I have taken more than a passing interest in nutrition – particularly when I was a new mother – and food generally, as I like cooking. I can therefore state with some confidence that there are simple and complex carbohydrates and that both are absorbed into the digestive system as sugar. Yes, sugar. The difference is that simple carbohydrates don’t take any breaking down – they can more or less be absorbed in the form in which they are ingested, meaning that the person eating them feels satisfied for less time than if he or she is eating complex carbohydrates – which take longer to break down. Therefore, if you eat lots of simple carbohydrates – such as sweets, biscuits and soft drinks – you are more likely to feel hungry again sooner and therefore to get fat, especially if the next lot of food that you eat also consists of simple carbohydrates. Simple, isn’t it? (If I haven’t got this right, I invite those of you with a firmer grounding than mine in science to correct me.)

So far, so good. I have no quarrel with any of that, except to point out that simple carbohydrates are not always ‘bad’ – they can be very useful if, for example, you are out on a hike and need an extra boost. Think Kendal Mint Cake or Dextrosol tablets. And not all simple carbohydrates contain only ‘empty’ calories: some have vitamins, minerals and electrolytes that aid recovery from strenuous activity or illness – Lucozade, for example (though I accept that the same benefits can also be acquired through the consumption of more natural products, such as milk).

What I really want to contest is that the current witch-hunt to track down and vilify sugar seems to me to have confused simple with complex carbohydrates to such an extent that natural foods as well as manufactured ones are now being targeted. And, as I’ve indicated at the beginning of this post, the newspapers, which can often be relied on to counterbalance the government’s more ludicrous excesses with a little cod-wisdom of their own, have on this occasion jumped on to the same bandwagon. Take last Saturday’s edition of The Times, which contained a full-page illustrated feature called ‘The Good Sugar Guide’. At the top of the page, it says that the WHO recommends that we don’t eat more than six teaspoons of sugar per day. If you look down the chart, you will see that one of the biggest sugar ‘culprits’ is the banana. A banana contains, on average, seven teaspoons of sugar.

Exactly what kind of advice is being offered here? Are we being exhorted to give up bananas, that mainstay of just-weaned babies, children’s teas, lunch-boxes and commuters’ breakfasts on the hoof? Bananas, which have in some regions been a foodstuff since the dawn of mankind, and which are known to have a wide range of nutritional and medicinal benefits? (If you’re interested, some of these are listed at http://www.botanical-online.com/platanos1angles.htm.) Or are we supposed to eat six-sevenths of a banana today and save the rest of it for tomorrow, not minding that the remaining seventh is now brown and sludgy and possibly contaminated with bacteria? Or perhaps eat six-sevenths of the banana today and throw the rest away? Nothing else with sugar to be eaten, mind!

The chart proclaims, conversely, that a large glass of red or white wine contains only one quarter of a teaspoon of sugar. Now, I like a glass of wine as much as anybody – I’d say I am definitely in the top quartile of oenophiles. But even I baulk at the prospect of drinking twenty-four glasses of wine to meet my daily sugar requirement.

I’m exaggerating the case to the point of absurdity here, of course – but only so that I can point out that so is the government. I’d like to suggest that there can be no more futile a waste of time, and no more dangerous an exercise, than to confuse and worry people with a chart that lists a heterogeneous collection of foods of widely varying nutritional value with the sole purpose of isolating the sugar content and, on top of that, to fail to distinguish between added sugar and sugar that occurs naturally. We don’t need a nanny state to poke its nose in in this very unhelpful way. And we certainly don’t want to start paying tax on bananas. May I also suggest (if you’ll forgive the pun!) that bananas are low-hanging fruit as far as the government is concerned? Almost everyone eats them: all the major supermarkets rank them in their top five bestsellers. What the government needs to concentrate on instead are the thornier and more serious challenges: tobacco, marijuana, alcohol, ‘hard’ drugs, abuse of prescription drugs, and the rest, and leave us to take care of the sugar, in its various forms.

I feel an urgent need to wolf down a banana. I might have a glass of wine (gosh, alcohol), too. Excuse me.

And then… there’s cake…

The verse venue: Matthew Hedley Stoppard and Ralph Dartford at Rickaro Books

Rickaro Books, of Horbury, is one of our most distinguished independent bookshops and, like all distinguished independent booksellers, Richard Knowles knows that events don’t just happen: you have to work at them. Therefore, although World Book Day – and, by extension, World Book Week – is getting a huge amount of support from the Booksellers Association and individual publishers, with lots of media coverage, whether or not a bookseller succeeds in making it work is down in the end to himself or herself.

Richard has arranged events for almost every day of this week, leading up to World Book Day itself, which is tomorrow, Thursday March 6th. (If you’re interested in finding out more, please click here.) Tomorrow, he is entertaining a group of schoolchildren in the shop, all wearing fancy dress, and is even going to dress up himself! (I find this amusing: Richard has obviously mellowed since I worked with him all those years ago, when, if not exactly child-unfriendly, he was certainly selective about the children that he liked!)

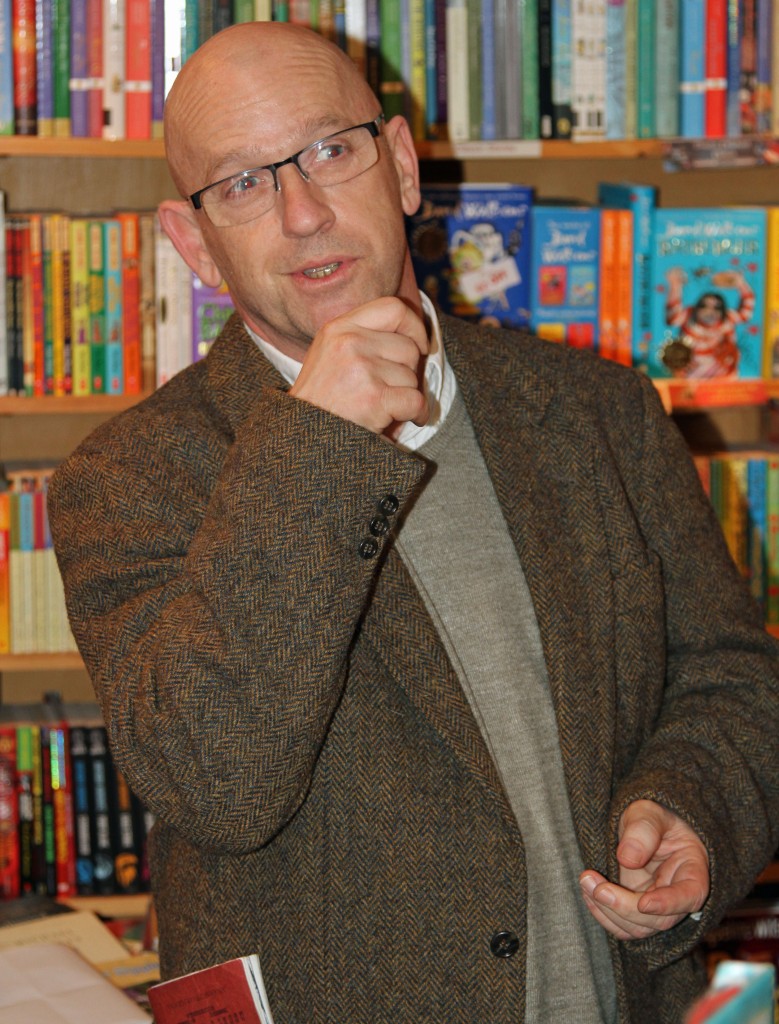

However, when I read about Richard’s celebrations for World Book Week, the Rickaro Books event that most intrigued me was the one that took place yesterday. I made plans to attend it immediately. It was a live poetry evening, with Ralph Dartford and Matthew Hedley Stoppard (who refers to himself on Twitter as ‘the poor man’s Benedict Cumberbatch’, a soubriquet that immediately endeared him to me). The shop has an excellent track record at organising poetry readings (I’ve written about them on this blog before) and I knew that yesterday’s would not disappoint.

The two poets recited alternately with the fluency and skill which comes from complete command of the material. Both were consummate performance artists, but what really impressed me was the quality of the poetry itself. It is my experience that many live poets are performers first, poets second, but both Ralph and Matthew are exceptional poets as well as being brilliant at engaging with a bookshop audience. The latter was pretty special, too, and included a small boy named George who was dressed as Peter Pan.

If you are not familiar with Ralph’s and Matthew’s work and you like poetry, I recommend that you invest in the two books (AND Matthew’s lovely green vinyl record!) that I bought last night. Cigarettes, Beer and Love, by Ralph, takes the form of a chapbook that has been beautifully produced by the Ossett Observer on hand-made paper. Matthew’s A Family Behind Glass, published by Valley Press, has all the elegance of a classic ‘slim volume’. Which poems did I enjoy most last night?

Well, the Co-op store in Ossett will never be quite the same to me again, now that Ralph has given me ‘Co-op Live Art Fiasco’, which describes his effort to show the individuals in the checkout queue that their investment in the Lottery pays for art (and his wages)… by stripping stark naked and doing some ‘live art’ with a Lucozade bottle. The constable summoned to the event says: “I once saw something like this in Berlin. A scratch card paid for the trip. I quite liked it.” (Ralph was led away at 08.46.) As readers of this blog know well, I’m game for a laugh, but there’s serious stuff behind Ralph’s humour.

Ralph describes Matthew as the ‘cerebral’ one of the pair (but all their poems last night were ‘thinky’, even the most superficially frivolous of them!). In fact, one poem of Matthew’s touched me a lot and spoke to me very clearly from my own past in our first rented marital flat in Leeds.

He set the context of a rented house in Rothwell, his and his wife’s first home, at a time when, he said, they weren’t really ready to be adults, yet. I’ll give you the first stanza, so that you may be touched as well:

Now that the streetlamps have stolen the stars

From the afternoon sky, sleep, content

And lovely as custard, pours over us. We sit

With winter on the settee, arm in arm –

Our legs interlaced like denim snakes,

Bedlam pressed between our palms. [From ‘The Wendy House’]

Matthew is about to take up a post with Leeds City Libraries: I’d like to wish him well with this. Ralph works for the Arts Council, and knows Chris and Jen Hamilton-Emery of Salt Publishing. He observed, unsurprisingly, that they are both ‘lovely people’. He kindly bought In the Family before he left the shop, which gave what had already been a very enjoyable evening a considerable extra fillip for me!

I wish Richard every success with World Book Day. (I’d love to be a fly on the wall when he receives the schoolchildren tomorrow, but unfortunately I have to travel to London instead.) And I hope very much indeed that I shall meet Matthew and Ralph again. In the meantime, I shall enjoy reading their poetry for myself. Thanks to them for introducing me so beautifully to it.

Precious poetry pack

Precious poetry pack

How to get a book signed by two priceless poets

How to get a book signed by two priceless poets

I want some clichéd spring!

Like most writers, I abhor clichés, but one cliché that makes me glad each year is the certainty of the English spring, in all its sweet naffness: little lambs gambolling, pale flowers bursting into bloom, pussy willows, forced rhubarb and chocolate cream eggs jazzing up the fare in the supermarkets… and all of the 101 other things that mean that winter is being pushed off into exile. And, if I hadn’t realised this before, last year’s spring (which, if you remember, didn’t happen) left me mourning for an annual cliché that was then even more powerfully etched into our minds by its absence.

When I was young, I didn’t mind heading into the winter: autumn meant pristine new school exercise books or, some years later, the excitement of a new university year; it meant going home in the slightly scary darkness; it meant that the ice cream van that had stood at the end of the street on long summer Sundays had been replaced by the toffee apple man’s van (he who vigorously summoned the children of the neighbourhood by ringing an old school bell out of his window); it meant chestnuts and hot toast and Heinz vegetable soup. But that kind of cosiness and the underlying slightly edgy sense of the danger that might be lurking in the dark (and would, perhaps, grasp you in its claws if you were sent up to Mrs Dack’s shop for some milk after the 6 p.m. news) has long since been replaced for me by the dreary feeling of unwell-being that winter brings: of snivels and snuffles, mornings that are wet and foggy rather than icy and bright and, in the part of the world where I now live, mud, mud and more mud.

I think that much of the problem lies in the fact that we English don’t ‘do’ winter well. Go further South in Europe and the Italians and Spanish celebrate short sharp winters that include coping with heroic bursts of snow before getting back to the norm of a balmy spring-to-autumn of sunshine that lasts for eight months of the year. Go North, and you find Germans, Scandinavians and Russians revelling in the winter, showing off their prowess on skis and skates, sometimes with a great deal of bravado. (A few years ago, I had a Finnish client (day-job) who boasted that he always skied in T-shirt and shorts.)

Perhaps the only country that is as bad at wintering as we are (or worse!) is France, but the French people that I know seem to solve the problem by going into virtual hibernation: The weather is foul – they stay at home – and eat and drink, mon brave, and sulk until the spring appears. Then there are the Scots, whose winters are colder and gloomier than ours and who succeed in behaving in a correspondingly chill and more lugubrious way. However, there is a grandeur about their melancholy: it is a Carlylean gloom of grandiose proportions, not to be compared with the trivial gnat-like whining about the weather in which we English indulge. And, like the French, the Scots understand that the only way to get through the winter is by eating the appropriate food and taking a wee dram whenever the opportunity presents itself. I endured three Scottish winters when I was working in Dumfries (home of the deep-fried Mars Bar, though even Dumfries folk regard this delicacy as an extreme remedy, to be used only at times of urgent necessity) and I have to admit that getting through day after day on six hours of daylight was not easy. At the place where I worked, we were supported through the winter months by the culinary achievements of our two stalwart canteen ladies. Menu favourites were meat and tatties, beefsteak suet pudding and haggis or hash with chips. If we asked for something light, they served up lasagne. I once suggested that a winter salad would make a nice change and they nearly fainted. ‘Salad? In the winter? How will you get the energy to do your work, hen? How will you keep warm while you’re working?’ (Of our workforce of 160, half a dozen worked in the packing bay; the rest of us were seated at desks, with the heating turned up a good 5 degrees higher than was strictly necessary.) Yet perhaps they had the right idea: we were trapped in the catastrophe of winter, and they were battling with it on our behalf.

So I say again that the English are the most hopeless of all nations when it comes to winter. But we are good at spring, and especially at perpetuating the clichés that go with it. Tomorrow is the first of March: not officially spring yet, therefore, but good enough for me! And I invite you to celebrate it with me in whatever joyful, hackneyed way you wish.

[Being as usual snowed under (a winter metaphor indeed!) with work, I asked my husband to take some clichéd photos to go with this post, but, with his usual delicate touch when behind a camera, he has instead, I think you’ll agree, managed to capture some extraordinarily un-clichéd pictures from what would otherwise have been very commonplace spring-time situations.]

Called to serve…

First of all, I’d like to apologise to everyone who reads this blog for having been so silent lately. I’ve been doing jury service, which has knocked the wind out of my sails much more than I expected – partly because I’ve had to keep up with bits of the day job as well (in particular, the March conference for which I organise the speaker programme), partly because it was quite a debilitating experience. However, I’d like you all to know how much I appreciate your continued interest in the blog and I promise to do better in future, starting with today!

I’m not going to write too much about the trial itself, as I don’t think that this would be fair, particularly as the judge has yet to pass sentence on the two defendants (whom we found guilty on one of the three counts, not guilty on the other two), but I should like to reflect briefly on the overall experience.

I was first called to serve on the jury of a much bigger trial, of a doctor who is accused of thirteen counts of rape that are alleged to have taken place across four decades. I’d very much like to have been one of these jurors, but the judge warned that this trial would last for at least six weeks, so I had to ask to be excused, because of the very conference I’ve already mentioned. I was a little apprehensive about it, because this judge was quite strict about which excuses he would accept – he didn’t rate lambing as a good one, for example.

I’d been warned by others who’ve done jury service that it involves a lot of waiting about. This is true, but the only really tedious bit is waiting to be assigned to a trial. I was assigned to ‘my’ trial on the morning of the second day – not bad, considering I’d already been asked to serve in the rape case – but at least one juror in waiting who arrived at the same time as I did on the Monday morning was still waiting to be called at the end of the first week!

Jurors are repeatedly told that they are the most important people taking part in a trial, because, of course, it is their verdict that finally finds the defendant guilty or not. Despite this, being a juror was curiously like the first day at primary school – trouping around with a group of other people, all of us united in not really knowing what we were supposed to do next. We soon got the hang of it and we had a particularly nice court usher looking after us – a woman called Shirley who, surprisingly, said that one of the most interesting cases she could remember involved a dispute between neighbours over bees (she indicated that, after a while, ushers become blasé about rapes and murders, because they have to listen to evidence about so many). My ears pricked up at this, as my husband keeps bees, as does one of our neighbours, but (as far as I know!) their relationship is extremely amicable and mutually supportive and neither has yet tried to sabotage the other’s hives.

Even when a jury has been sworn in and the trial has started, jurors get lots of breaks. Some of these are to allow the lawyers to discuss ‘points of law’; some are because witnesses are delayed or there is some other hitch – for example, a policewoman giving evidence at our trial had to go back to her office to fetch her notebook. The jury sits out short breaks in an ante-room just beyond the court; if the break is likely to be longer, the usher escorts the jury members back to the jury waiting room, where there is a small café, a television and a supply of books and magazines. Jurors are given a swipe-card that allows them to spend £5.71 per day on drinks and food from the café. (The sum appears to be adequate for female jurors, while most male jurors need to supplement it!)

Jury service officially lasts for two weeks, but if the trial takes longer jurors have to serve longer; if the trial is shorter, sometimes the jurors are allowed to go early. Some jurors serve on four or five short cases, each of which lasts only a day or two. Our trial went on for eight and a half days, which meant that we had fulfilled our duty as jurors by the time that it was over. More than a day of this was spent on reaching our verdict – it was a difficult case for several reasons, not least being that the victims suffered from dementia and therefore could not testify.

As a crime writer, I had been looking forward to doing jury service and although, as I’ve said, I don’t intend to write about the trial directly, I’m certain that the experience will have benefited my writing. Nevertheless, I was unprepared for how physically and emotionally exhausting it would be – hence my long silence. I’d like to apologise again for this. Thank you for waiting for me.

Turning the eye upon our selfies…

I was struck by the appearance in Monday’s The Times of the Jan Van Eyck ‘Arnolfini Portrait’, a painting I have always found fascinating for its depiction of a wealthy merchant and his wife. The detail to be explored in this marvellous creation of character and setting has not only human but also symbolic value, suggestive of the real existence, aspirations and lifestyle of this couple in their Bruges home. It cries out: ‘Here we are! We are rich and wonderful people! Look at us!’ The most intriguing aspect for me is the reflection in the convex mirror on the wall behind the couple, depicting two figures, one of whom is commonly assumed to be Van Eyck himself. Velázquez later did much the same thing in ‘Las Meninas’, showing himself as painter of the scene. It’s a clever way of putting your personal stamp on your work. As well as that, Van Eyck painted boldly on the wall (in the style, popular at the time, of a maxim or moral text): ‘Johannes de eyck fuit hic 1434’ or ‘Jan Van Eyck was here 1434’. I’ve always found it pleasantly ironic that the painter should have muscled in on the proud self-declaration of the Arnolfini couple, in a kind of portrait-bombing that elbows aside the intended subject.

My mind jumped quickly to the concept of self, as presented by ‘Kilroy was here’ and graffiti tags: ‘Notice me – I’m everywhere – I can get into the most unlikely and bizarre places… because I’m wonderful!’ That too seems pretty ironic to me, as I feel that shouting out about myself or my achievements is de trop and immodest; creating a ‘Christina James’ brand and promoting my writing here on the social media, I confess, does make me feel uncomfortable, even though I accept the need for it in the current bookselling market and therefore join in. However, I know how I feel about those who simply churn out plugs for their books without any engagement with others – it’s so much spam. Van Eyck’s skill sold itself and I suppose all writers and artists and craftspeople hope that the quality of their handiwork will do the same and that people will notice; in the meantime, they give it what they consider a helpful push. Shakespeare definitely, with his choice of the word ‘powerful’ in Sonnet 55, knew the value of his own words in outlasting even the hardest stone (‘Not marble, nor the gilded monuments of princes, shall outlive this powerful rhyme.’) and was clearly right to say so: his sonnet certainly seems to be standing the test of time. So… we turn the words and polish them, with ‘perhaps’ floating in our heads… and promote them.

Which in turn leads me to the ‘selfie’, a bizarre bi-product of the technological society in which we live. We have a ‘smart’ phone (there’s a misnomer) which we can turn upon ourselves with no skill or effort whatsoever and take our own picture. Why? Narcissus fell in love with his reflected image, because Nemesis, having noticed his overweening pride in himself, led him to the pool in which he saw himself and he couldn’t drag himself away from the image in its surface; he therefore died, his hubris preventing him from seeing reality. Messrs Obama and Cameron, perhaps flattered by the photographic attentions of the personable Danish PM, fell into much the same trap, losing their sense of reality in the process. Not only did they use no art in the creation of the resulting silly picture, but also failed to use even the most basic commonsense, and Mrs Obama and the rest of the world clearly eyed them with the sharp vision of objectivity. Oh dear. The ‘selfie’ doesn’t work very well as a self-promotional tool.

I didn’t set out to be moralistic, but this is beginning to feel that way. We care about what we create and care about how others view it; there is ‘self’ in that! I have been privileged to receive positive reviews about Almost Love from writers whose own work I value and enjoy and I’m therefore sharply aware of how important it is to celebrate what I find successful and admirable in what others do; there is joy to be had in reviewing books that stand scrutiny. I’m also very much aware of how selflessly many of the people with whom I interact on the social networks behave; they deserve to feel proud of themselves for making someone else’s day. I’m glad, too, that the social media allow all of us to find our way to what we like; we’d miss out on some gems if their creators were utterly selfless!

Whitelocks

I’ve always had a strong affection for the very heart of Leeds and first knew it when the buildings were still black with soot and vehicles could go everywhere in what is now a huge pedestrian precinct. I particularly remember shopping here before Christmas in the early seventies and finding it almost impossible to make my way along the pavements, which were packed with shoppers because the roads were likewise thronged with cars. It is much more pleasant now, with space for pedestrians as well as pavement cafés (one in a street completely covered with a glass roof that seals it from the weather and gives it the feel of the various Victorian arcades that lead off Briggate) and talented buskers; the several covered shopping centres (the latest, Trinity Leeds, adjoining Boar Lane) are a magnet to thousands of visitors from across Yorkshire and beyond.

The casual visitor, however, will probably miss the ‘ginnels’ (passageways) and ‘yards’ that preserve the history of Victorian Leeds and that thread their way through the buildings a breath away from the main shopping streets. The entrance to the far-famed ‘City Varieties’ theatre is in one such, though it has been considerably changed and modernised. And in one of these, leading off Briggate and cheek by jowl with the Trinity Centre, is the oldest pub in the city, Whitelocks. I suppose that I, too, should have missed it, but my husband, who seemed as a student to manage to find his way to most of the hostelries in town, took me there many years ago. I went back with him to enjoy lunch there on my return from China.

Here, indeed, is local Leeds. Sitting alongside us were a grandfather (his accent marking him out as a Leeds man) and his two grand-daughters, both of them students, who bought him lunch and beer, put him in the picture about their mother, his daughter, and bid him a merry farewell as they headed off to afternoon lectures; to my left, during the time we were there, a succession of elderly Horsforth (I asked!) couple, a market trader I recognised from many years’ enjoyable shopping in Vicar Lane’s Leeds City Market and a younger man who came in to sup his pint and put the working day aside for a while. The long bar was crowded with suits on lunchbreak and large groups of city workers of one kind or another.

Whitelocks has to be seen and experienced first-hand: it is a jewel of Victorian/Edwardian décor, replete with brass and copper and marble and coloured tile and mirrors and stained glass and ironwork. It gleams with a sociable splendour that makes ‘having a drink’ into an occasion of moment. For the contemporary cognoscenti, the range of real ales is special, the food traditional and beautifully prepared. Here is an inn which cherishes its guests and makes them feel warm inside.

It opened as an inn in 1715, serving local traders and customers in what was then a Briggate market; its original name, The Turk’s Head, lives on as the name of the yard, but the inn was rebuilt and (as its blue plaque confirms) extended to absorb a row of Georgian working men’s dwellings by the first of the Whitelock family, who took over the licence in 1867 and transformed it. Fortunately, it has been preserved for future generations of Leeds folk to enjoy.

My imagination was caught by my first visit there, on a foggy November evening; there may not have been gas lamps, but there was gloom in the ginnel and a warmth of welcome within. The past reached out and drew me in, to think of the divide between the relatively wealthy Victorian and Edwardian customers of ‘Whitelocks First City Luncheon Bar’ and the vagabonds and urchins and footpads outside in the sooty darkness, who no doubt relieved some of them of their wallets and purses. For a crime writer, pubs with character and a powerful history have huge potential. I’m sure that Whitelocks could very easily find its way into a story and may very well already have done.

Memory the only takeaway from a magical Chinese experience…

It’s impossible to conclude my blog-posts about China without writing about the food. I’m not actually a big fan of Chinese food when I’m in England, principally because so many Chinese restaurants here adulterate their cuisine with monosodium glutamate. (The Chinese restaurant in which I worked when I was a student, which was home to the cook called Moon, star of a previous post, was an honourable exception.) If I consume this substance, which I believe is also called ‘Chinese taste powder’, I invariably get a headache and feel dizzy the following day.

However, I was assured that monosodium glutamate is never used in restaurants in China and I certainly didn’t detect it in any of the food there. I was very honoured to be treated with the utmost hospitality throughout my stay and, as food plays a big part in Chinese standards of courtesy, I was presented with what was effectively a banquet every night. Although when at home the Chinese usually confine themselves to three or four dishes, which in Shanghai always includes a soup (It was explained to me that soup helps to regulate the body temperature if the climate is hot and dry or if other foods are spicy.), when guests are taken out to eat it is not uncommon for ten or twelve main dishes to be ordered, as well as many appetisers and side dishes. These don’t all appear at once: the waiting staff bring them in one by one and place them on a huge circular glass ‘lazy Susan’ (the Chinese use the same words), which is spun slowly round by each diner in turn, with all the tantalising magic of what felt like a place at a gastronomic ouija board.

All the food that I ate in China was delicious: without exception, it was very fresh and featured many different kinds of vegetable (though an actual vegetarian would have a tough time there, as most dishes also include meat or fish of some kind). At every dinner there was also a whole sea bass garnished with herbs and spices – an expensive treat, presented to guests as part of the impeccable code of hospitality. I was only once offered a delicacy that I was reluctant to try: on my last evening in Shanghai, the pièce de resistance was a dish of pickled ducks’ tongues. One of my fellow diners told me that they tasted like mackerel, but I was too cowardly to find out if this was true!

Among my favourite foods were the exquisitely-crafted dumplings that usually appear after the main entrées. The smaller ones contain meat, the larger ones a special soup: they require eating with great care, so that none of the soup is lost.

Rice and noodles are served separately at the end of the meal, because guests are encouraged to eat their fill of the finer dishes before filling up on these staples. Desserts are simple and light, consisting usually of sweet soups (plum is a favourite) or yogurt and honey. Tea is the main beverage. Light beer is also served, but drunk sparingly. Wine was not served at any of the dinners that I ate and no alcohol was ever served at lunch.

My two Beijing dinners were particularly special. The first was at the original Peking Duck restaurant, which is close to the main campus of Peking University (The University retains the name ‘Peking’, choosing not to call itself ‘Beijing University’ because it is proud of its heritage. It is China’s oldest and most prestigious university.). This restaurant has been serving Peking Duck since the 1930s, when it invented the recipe.

Each diner is given small dishes of cucumber, chopped spring onion and plum sauce and a round box of steamed pancakes. I discovered that Peking Duck is one of the most authentic dishes served in Chinese restaurants in England. In Beijing, the duck itself was oilier and therefore richer than in the UK, but apart from that the taste of all the ingredients was similar: the key difference was the dexterity with which the waitress demonstrated how to flip the pancake on to the plate with chopsticks, fill it and form it into a neatly-wrapped parcel. None of my parcels looked like hers! As they leave, diners are given a certificate to prove that they have eaten genuine Peking Duck in this restaurant.

On my last night in Beijing I enjoyed the most special dinner of all. It was a banquet held in the ‘Emperor’s Palace’, a restaurant whose real name is the Bai’s Home Courtyard. It was originally the palace home of Prince Li of the Qing Dynasty. The courtyard is in fact a succession of formally laid-out gardens, each one containing a single-story building that once formed part of the Emperor’s palace and has now been converted into a dining-room. The buildings are guarded by young men dressed in the traditional garb of Imperial soldiers, and the waitresses are young women attired in beautiful traditional silken costumes and head-dresses.

On their feet they wear tall pattens – the platforms of these, on which the centre only of the foot is balanced, are about four inches off the ground. One of the girls told me that it takes a week to learn how to walk in these shoes. Twelve of us ate that evening and we were served throughout by four silk-clad waitresses. Our dining-room was dedicated to longevity, symbolised in the detail of the wall-hangings.

The table was round, for equality, and all the chairs except one richly covered in yellow silk; this single chair was made of intricately-carved wood. Originally, it would have been the one in which the Emperor sat. No woman ever sat in the Emperor’s chair – at least, not then!

We were served perhaps two dozen dishes at the Emperor’s Palace, some of them tiny, all of them delicious and beautifully presented. My favourites were a very special kind of smoked fish and venison stewed with chillies. The banquet lasted for about three hours. Once outside again, we discovered that it had turned bitterly cold – some of the fountains in the gardens had frozen over and the walkways as we made our way back to the street were lit with bright orange lanterns that picked out the tiny dots of silver frost on the profusion of plants flourishing on the small ponds and spilling over the low formal walls designed to contain them.

It was a magical, almost an enchanted, evening, a marvellous culmination to eight days of extraordinary new experiences. If I did not have the photographs, I might believe that I had dreamt it.

All text and photographs on this website © Christina James

Mighty river…

On my travels in other countries, some of the most evocative moments have been spent contemplating rivers. I’ve stood on O’Connell Bridge in Dublin and watched the (on that occasion very murky) waters of the Liffey and remember thinking, as I looked into its Guinness-coloured depths, that it must have been entirely James Joyce’s poetic imagination that produced such a beautiful name as Anna Livia Plurabelle. I’ve seen dhows swooping along the Nile, their single white sails bending gracefully to the breeze. I’ve marvelled at the massive businesslike barges speeding along the Danube, powerful and swift as crocodiles on the move. The bridges and embankments of the Seine are still vividly precious for their romance on our honeymoon. Closer to home, as I’ve written in a previous post, I’ve admired the spectacular night-time views from Waterloo Bridge in London as the Thames makes its sudden sweep to the East. And I still feel great affection for the dear, dirty River Welland that threads its way through the town of Spalding, much humbler than these great waterways, though still, in its day, a significant bringer of prosperity to the people who dwelt nearby, just like all the great rivers of the world.

Unsurprising then, that I should have been captivated by the magic of the great Yangtze, the fourth longest river in the world, as it pours itself at Shanghai into the East China Sea. Wide and fast-flowing, the Yangtze has brought traders to Shanghai for thousands of years, making it one of the world’s great cosmopolitan cities long before the rest of China emerged from its self-imposed insularity.

Even the Yangtze’s much smaller tributary, the Huangpu River that cuts right through the city centre, is a majestic waterway, which I visited first on a cold but sunny Sunday afternoon when people were promenading along the Bund, the waterfront area opposite Pudong, on a built-up walkway that enables walkers to get close to the river’s banks and where festive street food stalls abound.

Two days later, on a bitterly frosty but fine, clear evening, I was taken to the Huangpu’s junction with the Yangtze. On both occasions I was able to watch barge after nimble barge (they are longer and slenderer than the ones on the Danube) power by, almost as if in convoy, while the waters displaced by their passage lapped energetically against the shore. The barges and other ships are lit up in the evening, as is the spectacular Shanghai skyline that forms a backdrop to the Yangtze. The result is a profusion of golden lights that disport themselves against the inky blackness of the waters. The scene is dynamic, full of energy and passion, the legacy of very many years of trade, hard-won prosperity, daring, risk and chance and, I’m certain, not a little skulduggery and murder. The effect is by no means cosy, but it is exhilarating! At the back of my mind lurked the half-remembered knowledge that, in years gone by, to be ‘Shanghaied’ meant to be kidnapped and forced to serve as a sailor on board one of the many ships that plied their trade to the East and, ultimately, to Shanghai. I could imagine someone creeping up on a strong young man as he stood, unsuspecting, and rendering him unconscious; imagine his anguish as he awoke, his head sore, far out at sea, unable to tell his family and friends what had befallen him… that he was on his way to China.

Every river has a personality, which I think was James Joyce’s point about the Liffey. The Yangtze’s is particularly complex: on the one hand, it courses past Shanghai, bearing its gift to this great city of enterprise and generations of toleration for many creeds and cultures; on the other, it penetrates deep into a country that until recent times was secret, withdrawn, enclosed and shut away from all outside influence.

All text and photographs on this website © Christina James

For all the tea in China, I’d need several fortunes…

This is my first full day at home after my visit to China, and I’ve just enjoyed a nice cup of tea. Tea is one of our national clichés – the universal British remedy for everything, from broken hearts to bereavement, and also the beverage that most Brits look forward to the most when returning home from foreign adventures. However, I can hardly claim to have been tea-deprived during my five-day sojourn in Shanghai or the two days I spent in Beijing. Tea is what you drink with every meal in China, and there are hundreds of different kinds. I managed to sample a few of them, sometimes in very special surroundings. It is served with some ceremony in restaurants: waiters hover with teapots and fill your cup again as soon as you’ve drained it. As with wine, special kinds of tea are recommended for some types of food: for example, a rich, smoky tea accompanied the duck that I ate in the original Peking Duck restaurant in Beijing (more of this in a separate post). Tea is also used in very traditional restaurants to cleanse crockery and cutlery at the table.

I had only two half-days to myself, as mine was a business trip, not a holiday, but, aided by some kind Asian colleagues, I was able to make the most of them. On the Sunday after I arrived in Shanghai, I took a taxi to the Yu Garden,

a mesmerising complex of temples, waterways and ancient shops, and, after an hour or two of sightseeing, found myself standing outside the fabled Huxinting Tea House, the oldest tea house in Shanghai (the building is about 230 years old, becoming a tea house in 1855).

Naturally, I went in and was delighted to find that I’d chanced upon a mid-afternoon lull in business, so it wasn’t too crowded.

Inside, the tea house is opulent but not flamboyant. The waitresses are dressed in a uniform based on one of the many forms of Chinese national dress and they are attentive but unobtrusive. There are scores of types of tea to choose from, some of them extremely expensive. I chose jasmine, which came in a glass jug and was accompanied by two aromatic sweetmeats.

It was quite delicious: fragrant and refreshing, exotic without being strange. It wasn’t cheap, either: it cost the same as a couple of lattes from Starbucks would have cost in the UK, which by Chinese standards is very expensive indeed. But it was well worth the price: I understand why Chinese people think that the tea house is so special and come here for a treat. It’s not only the ambience inside the building itself that gives so much pleasure; it is also being able to look out across the water of the lake in which it stands on stilts to the picturesque buildings beyond. The paths and walkways are always teeming with people and the tea house itself offers a haven of tranquillity from which to observe them, as well as a feeling of privilege. The elderly couple sitting next to me were obviously savouring every moment, whilst also engaging in a very animated conversation.

Each type of tea is served in a different type of vessel and theirs was in terracotta pots with lids, which they had refilled more than once. I’d have loved to have been able to ask them what their choice had been.

Since I came home, I’ve read about the Huxinting Tea House online and discovered that the Queen has visited it. I don’t suppose that she had to worry about the cost of her tea, but I do wonder if, having imbibed its product, Her Maj was constrained to use the establishment’s facilities. If so, I’d like to know what she made of the shaft-style convenience,

which was the first, but by no means the last, of this type of porcelain that I encountered in China. (I should add that the one in the Huxinting Tea House was spotless.)

I wanted to bring some tea home with me, but was advised against buying it from one of the specialist purveyors of tea or at the airport as being prohibitively expensive in either. On my last day in Beijing, I therefore walked to a local supermarket and bought two types of tea there, one of them a chrysanthemum tea that I’d first seen earlier in the week when it was ordered by a librarian during a conference that took place at Shanghai Jiao Tong University. On that occasion, it was served in a tall glass mug with a mash of dried chrysanthemum flowers floating on the surface of the hot water. More prosaically, I think that my own purchase will consist of more conventional-looking tea leaves, albeit made out of chrysanthemums. Chrysanthemum tea sounds unpleasant – I was sceptical until I tried it, thinking that it might taste as the half-dead ‘chrysanths’ which I remember adorning the graves in Spalding Cemetery used to smell, but in fact it is delicate to the taste-buds and very refreshing.

Going to the supermarket offered me one of only a few rare opportunities to encounter ordinary Chinese people as they went about their business. I was grateful for this experience. Once again, I was also astounded by how expensive the tea was and how greatly prized. In the supermarket where I bought mine, it was kept upstairs with the alcohol and closely guarded by a security man. It cost about three times as much as a packet of ‘builder’s tea’ in England. I wonder what Chinese builders drink? I’d like to think that their day is fuelled by an infusion of chrysanthemums!

All text and photographs on this website © Christina James