Warning, this post is not for the prudish…

A physics professor from the University of Cambridge has objected to a sexually-explicit passage from Ovid’s Amores that was set as part of this year’s Cambridge OCR Board AS-level paper (the candidates sitting the exam will therefore mostly have been 16 or 17). Apparently, he thinks that the piece was unsuitable for students of this age, because the examination rubric states that ‘candidates should be able to … produce personal responses to Latin literature, showing an understanding of the Latin text’.

As an aside, I’d be prepared to hazard a guess that at least some of the examinees were not as innocent as the professor supposes. However, I do not need to speculate on how knowledgeable they may have been on the subject of the piece – an adulterous liaison between the poet and a married woman – because that is not the issue. If it were, then examinations would also have to exclude literary works that refer to all crimes, including murder, and all works set either in the past or in foreign countries unknown to the candidates. That would rule out the whole of Shakespeare, the whole of Jane Austen and most modern masterpieces. Surely the point of great literature is that it has the power to evoke an imaginative response in the reader that transcends his or her actual experiences. It achieves a fusion between art and life that yet maintains intact the distinction between the two. As Orhan Pamuk puts it so eloquently in The Naïve and Sentimental Novelist, “We dream assuming dreams to be real; such is the definition of dreams. And so we read novels assuming them to be real – but somewhere in our mind we also know very well that our assumption is false.”

What is depressing about the good professor’s comments, however, is not their patent absurdity (he is a professor of Physics, after all, not of Literature), but the fact that they signal a deadening retrogressive trend that is in danger of spreading beyond the confines of the classroom. I was a schoolgirl during the tail end of a period when some school texts still in circulation were described as ‘abridged’ or even ‘expurgated’: for example, my rather old-fashioned grammar school still had many sets of the Warwick Shakespeares. They had been relieved of all scenes of a sexual nature and any words that could be construed as ‘blasphemous’. However, by then, these texts were still in use for reasons of economy, rather than to preserve the pupils’ innocence. When we came to the examinations, we were expected to have read the full-fat versions. Teachers advised us to refer to these in the Collected Works, or sometimes reproduced the excised passages on separate cyclostyled sheets of paper.

To my knowledge, the Latin texts that we studied had never been subjected to the same cleansing process: my Latin ‘A’ Level syllabus included the original works by Juvenal and Catullus – much racier than Ovid – as well as Ovid himself. I cannot remember having had any difficulty in understanding them or of their having caused offence or difficulty in the classroom. What I do recall is how fresh and original they still seemed, two millennia after they were first published, and the brilliance of the teacher who helped us to appreciate them.

I’m delighted that Mary Beard, Professor of Classics at Cambridge, has robustly defended the choice of excerpt in the Latin exam paper, because I’d hate us to slide backwards into a kind of dark age of political correctness in literature. Today we are scornful of Nahum Tate’s version of King Lear, in which Cordelia marries Edgar and all the ‘good’ characters live happily ever after. We are positively amused by the efforts of Thomas Bowdler, who not only supervised the production of a ‘family edition’ of Shakespeare, but also considered that Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire was too risqué for polite society, and ‘improved’ it accordingly. More recently, my generation was exasperated by Mary Whitehouse’s well-meaning but narrow-minded attempts to clean up television.

We flatter ourselves that we live in a more sophisticated age than Tate or Bowdler. Many of their contemporaries, in fact, looked askance at what they were trying to achieve, just as my generation ridiculed Mary Whitehouse. Yet fashions in morality and what is ‘acceptable’ often don’t progress in linear fashion, making the next more discerning than its predecessor. In the nineteenth century, English literature was propelled at first slowly, then ever more rapidly, from the exceptionally daring creativity of the Regency era to a decades-long period that celebrated anodyne writings in which sexuality had to be conveyed in the strange telegraphese of young girls’ blushes and young gentlemen riding hard to hounds to quell their natural yearnings. Alternatively, these characters just faded away, blissful in the knowledge that their virtue had not been compromised. Woe betide the ‘fallen woman’, whose plight was not recognised until the end of the century, when Thomas Hardy wrote Tess of the d’Ubervilles.

When I was at school, it was a commonly-held belief that Physics was a finite subject: that mankind had ‘cracked’ it and had discovered all that there was to it. I know very little indeed about science, but I have read that today Physics is an incredibly exciting as well as very complex subject, one which attracts the finest minds as scientists push back the boundaries of knowledge all the time. I both respect and am in awe of them. I would suggest that they have at least one thing in common with those who choose to make literature their life’s work: they build on the creativity of the generations that preceded them. As far as I know, there is no expurgated version of Newton or Einstein: the only limitations placed on their students concern the latters’ capacity for understanding. The same restriction, and this restriction only, should apply to those who study Shakespeare, Catullus, Juvenal – and Ovid.

An admission of ignorance…

A web-developer named Christopher Pound has carried out a text data mining trawl (I shall write about text data mining in another post – it is a bit of a hot topic in some publishing sectors at the moment) to reveal the 100 most popular books by different authors to be accessed via the Project Gutenberg free e-book site. Books for both adults and children are included. The top 10 from both categories are:

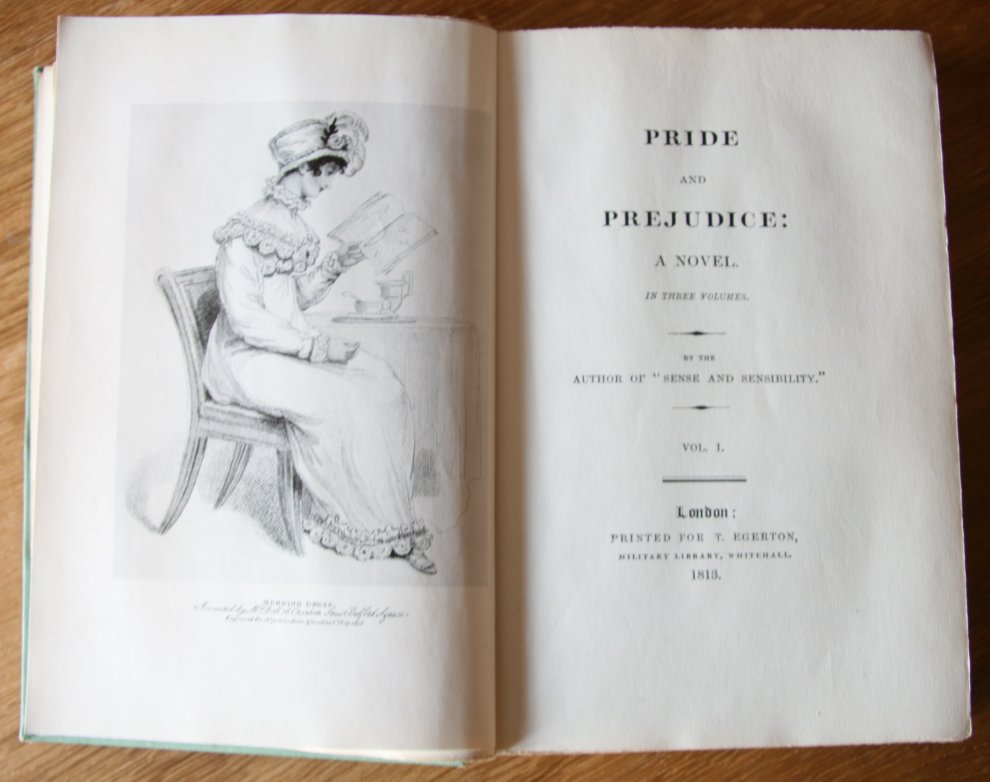

1 Pride and Prejudice (Austen, Jane)

2 Jane Eyre (Brontë, Charlotte)

3 Little Women (Alcott, Louisa May)

4 Anne of Green Gables (Montgomery, L. M. [Lucy Maud])

5 The Count of Monte Cristo (Dumas, Alexandre)

6 The Secret Garden (Burnett, Frances Hodgson)

7 Les Misérables (Hugo, Victor)

8 Crime and Punishment (Dostoyevsky, Fyodor)

9 The Velveteen Rabbit (Bianco, Margery Williams)

10 Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Twain, Mark)

Can you spot the odd one out? Or am I just revealing my own crass ignorance when I say that I have never heard of The Velveteen Rabbit? According to Wikipedia, this book, which was published in 1922, was selected as one of ‘Teachers’ Top 100 Books for Children’ by the (American) National Education Association in 2007. Apparently it has also been the subject of numerous film adaptations, talking books, etc. Wikipedia sums up the plot as follows: A stuffed rabbit sewn from velveteen is given as a Christmas present to a small boy, but is neglected for toys of higher quality or function, which shun him in response. The rabbit is informed of magically becoming Real by the wisest and oldest toy in the nursery as a result of extreme adoration and love from children, and he is awed by this concept; however, his chances of achieving this wish are slight.

Peter Rabbit, Alice in Wonderland, Heidi and Uncle Tom’s Cabin all appear in the Top 100, but considerably lower down in the list.

Statistics like these always make me want to know more. Why has The Velveteen Rabbit proved so popular, at least when accessed via Project Gutenberg? It isn’t because it’s not available in print: Amazon lists it and states that there are both print and talking book versions available. Is it because American teachers are more likely to direct pupils to e-book sites than teachers in other countries? Do they perhaps even download it and arrange for it to be printed for their classes via a Print on Demand company? Or, as I’ve suggested, is it just that there’s been a blip in my education? In fact, several blips, because in all my years as a bookseller and library supplier, I have never come across either this book or its author.

Here is Christopher Pound’s full list.

Something that I look forward to…

It’s just occurred to me that it’s been a long time since the last Crimewatch programme, so I’ve looked it up on the BBC website and discovered that the next episode will be on Thursday. Something to look forward to later in the week! For visitors from overseas, this appeal programme features real unsolved crimes and asks for help from the public to pinpoint the perpetrators.

I’ve been a Crimewatch fan almost since it began. In the early days, I was attending quite a demanding evening class and would rush home afterwards to see it. I always missed the first twenty minutes or so, which made the remainder of the programme all the more enjoyable. I don’t like the glitzier image of recent years as much as the more straightforward regime presided over by Nick Ross, but I still hate to miss it. This week’s episode is on the rise of mobile phone thefts, apparently, which doesn’t sound riveting… but we shall see!

I haven’t often been bored by Crimewatch, but I do favour some of the regular sections over others. I like the rogues’ gallery, because it’s fun to speculate and put the face to the crime – though I realise that such games are purely subjective, for one thing, and, for another, fail to take into account the fact that police mugshots, like passport photographs, are bound to look sinister, because the subject is forbidden to smile. I’m always absorbed by the reconstructions, which tend to feature murder or rape. Sometimes I wish I could call out to the victims, tell them not to take that shortcut or forget to lock their door. Clips that I like least tend to feature CCTV footage of mindless violence – although I know that it is right to highlight this – or what can perhaps be best described as a dark sister of the Antiques Roadshow: the parade of artefacts discovered by police to be in the possession of criminals who can’t or won’t say how they came by them. I know at first hand that theft is a foul crime: my house has been burgled twice and I’ve also (as you may have read here) had my purse stolen. But somehow this collection of inanimate objects doesn’t engage the attention in the same way. Clips that show those bereft of treasured items and asking for their return are a different matter; I can empathise with the victims completely.

Best of all, though, are the retrospectives. Sometimes a whole programme is devoted to these. If this programme is additional to the season’s schedule, that’s a bonus. What’s so fascinating about the retrospectives is the way in which they provide step-by-step documentation of how the villains in a previously featured case have been caught. (Understandably, crimes which Crimewatch itself has helped to solve are most frequently chosen.) I’m not a police procedural writer, as my readers know, although this is a very palatable way of finding out how the police operate, but it’s the insight into the criminal mind offered by the retrospectives that really grabs me. Sometimes the perpetrator has shown such Machiavellian cunning that I’m full of admiration for the police in outwitting him or her; sometimes s/he seems to have behaved in such a stupid or reckless way that it’s surprising that they weren’t apprehended immediately.

If you have access to British TV (I know that this doesn’t apply to everyone who will read this) and you haven’t seen Crimewatch before, I invite you to join me on Thursday evening, 30th May, BBC1 at 9 p.m. If you are already a fan, I look forward to keeping you company! Perhaps we can compare notes afterwards.

‘even MPs fail to speak properly’ – Oh, the glorious irony of that word ‘even’!

I was amused to read in today’s paper that standards of grammar are slipping ‘even‘ among MPs. I’m amazed that the author considers the linguistic prowess of politicians to be the yardstick for the nation’s performance in this respect. For years I have been entertained by the dreadful but often hilarious ways by which MPs mangle the language. Those most self-consciously aware of the way in which they speak are prone to make the worst gaffes. Mrs Thatcher’s Tudoresque announcement “We have become a grandmother” is etched on the national memory. Very recently, Michael Gove, that staunch advocate of traditional grammar school education who now wants to extend the length of school days to workhouse proportions, explained his rationale thus: “If you look at the length of the school day in England, the length of the summer holiday, and we compare it to the extra tuition and support that children are receiving elsewhere, then we are fighting or actually running in this global race in a way that ensures that we start with a significant handicap.” Crystal clear, mellifluous, grammatically rigorous and beautifully structured, isn’t it?

I’m not sure that I agree with the hypothesis that this slip in standards, if indeed it exists universally, is caused by shortcomings in our formal education; there may be a more profound cultural change at work. My grandmother left school at the age of fourteen with no formal qualifications. Although she was deeply interested in learning and continued to read widely throughout her long life, the number of days that she actually spent at school was pitifully small, because she was the eldest of nine children and expected to stay at home, sometimes for months, whenever her mother had another baby or one of her siblings was ill. ‘In service’ for the whole of her working life (which began when she was fourteen and finished when she was seventy-four), she prided herself on speaking ‘properly’. I remember what she said to have been always grammatically correct and exquisitely enunciated, although it was not delivered in what came to be known as ‘Received Pronunciation’, because she always retained the slight burr and elongated vowels of her native county, Kent.

Her speech was picturesque in ways that have almost been lost. I think she must have thought in pictures and she had a fund of sayings for every occasion. Not one to suffer fools gladly, she used these sayings to convey her opinion (relatively) politely, but with disarming directness: “Who’s upset your apple-cart?” she would say, fixing me with a bright eye if I were behaving in a sulky fashion; “No fool like an old fool,” she would trot out summarily if one of her sisters related a mishap that she believed had been the consequence of a stupid decision; “Cleanliness is next to godliness”, she rapped out at her neighbour, an old man to whom she always referred as ‘Hicks’ (she regarded him as not quite her social equal), when he told her that he was unable to perform his usual weekly task of carrying out her dustbin to the street because he had a painful boil on his neck. “Red hat, no drawers,” she proclaimed in a penetrating whisper when a lady sporting this outré headgear passed us in the street.

One of the most fascinating things about language is that it is a living thing. Like all living things, it changes and evolves. We seem to be experiencing a rapid period of change in our use of language at present. I don’t think that this means that it is in terminal decline. What will emerge will be a new set of ‘rules’. (How the rules change over time can be demonstrated by consulting early editions of Fowler’s Modern English Usage.) The reasons for the present shifts in usage seem to me to be complex: Some can indeed be blamed on ‘poor’ education, but, as my grandmother’s example demonstrates, adopting a lifelong reading habit is the most effective way of understanding language and using it well; some owe themselves to a rapid influx of imported words and sayings, predominantly (such is the power of media) from the USA; some happen because the speaker (e.g. Mr Gove), although well-educated, does not take care to present a series of related thoughts in a logical sequence. As any writer knows, when you have something complex to convey, crafting a series of short, simple sentences may be the best approach to take. Of course, we need to pay attention to these things, but above all we need to guard against allowing the lifeblood to be drained from our speech by becoming too ‘PC’. I’m not talking about being rude or slanderous, but, like my grandmother, we must continue to harness the power of the language itself to convey our true opinions, not hide behind some anaemic gobbledygook that has been dreamed up by the thought police, or politicians!

As a totally irrelevant aside, it was my grandmother who first taught me about irony. Visiting my mother one day, she announced that my Great-Uncle Arthur was in hospital with a chest infection and that my Great-Aunt Lily had ‘fallen up the steps’ on her way to see him and cracked three of her ribs. Both she and my mother were then overcome by a burst of spontaneous laughter. I was shocked at the time, but realised later that it was the irony of the situation that amused them, not poor Lily’s misfortune. Jane Austen, not herself the product of a formal education but the mistress of irony, would have smiled.

Mr. Gove, perhaps you may pontificate when you have acquired the verbal skills to do so!

Mayflower turf wars… anyone else want to join in?

I was disgruntled to read in yesterday’s The Times that there is some kind of battle going on between Harwich and Plymouth about which place really ‘owned’ the Pilgrim Fathers and the Mayflower. Both contenders are quite obviously charlatans: as every Lincolnshire schoolchild knows, the Pilgrim Fathers originated in Boston, from which Fenland town they had to flee as dissenters to the Netherlands. Subsequently they sailed to America, and founded a colony in Massachusetts, eventually naming its principal town… Boston! (See? Not Basildon or Barnstaple. Or Plymouth, indeed!)

The name of Boston, now borne with pride by one of the world’s great cities, should be sufficient proof that all other claimants to ancestral Mayflower fame are upstarts. However, I do acknowledge that the name of the rock on which they landed in 1620, which has always been known as Plymouth Rock, muddies the waters a little. But I’ve seen Plymouth Rock and, no disrespect, in a country that does everything BIG, it is perhaps the smallest and most understated monument that ever graced the description ‘tourist attraction’: a refreshing change from the biggest, richest, fattest and brightest (but rarely oldest) that is the more usual fare in America; yet, even to someone who thinks that small is beautiful, disappointing, nevertheless. And far from casting doubt upon my assertion, I think that Plymouth Rock proves it completely. Why? Because, with its limited dimensions, it’s quite obvious that no more than three people could have stepped ashore upon it. 102 people sailed in the Mayflower; two of them died on the voyage. Of the remaining 100, three obviously came from Plymouth; and the other 97 from Boston. In the absence of a rock bearing the legend Basildon or Barnstaple, and with a whole city to rely on, I rest my case.

Lincolnshire rules, ok?

BOOKS ARE MY BAG: WOW!

As a former bookseller, my heart was gladdened by attending the announcement of the Books are My Bag campaign, which for me was the most exciting single event held at the London Book Fair this year. The campaign has been devised by M & C Saatchi and is entirely based on a single, simple, very effective message: that the passion for books and bookshops is a precious part of our national heritage and something that we should cherish, celebrate and promote. It is a campaign of perfect solidarity: all booksellers (whether they belong to chains or independents) and publishers are uniting with one voice to celebrate the pleasures and cultural importance of the high street bookshop.

Tim Godfray, CEO of The Booksellers Association and Richard Mollet, CEO of the Publishers Association, both spoke at the event. They were joined by some industry legends, including Patrick Neale, currently President of the Booksellers Association and joint owner of the marvellous Jaffé Bookshop in Oxfordshire (in a previous life he was the inspiration behind the equally wonderful Waterstone’s Sauchiehall Street bookshop in Glasgow) and Gail Rebuck, Chair and CEO of Random House (who, like Dame Marjorie Scardino, has proved that women can get to the top of large corporate publishing houses and stay there).

Patrick’s message was strong and direct. He made the point perfectly that there is far more to the experience of buying a book than receiving a brown cardboard parcel through the post: “We all know that there are many ways to buy and sell books, but what Books are My Bag captures and celebrates is the physical; the simple truth that bookshops do more physically to let people enjoy their passion for books.” Gail Rebuck said: “In these challenging times for the UK High Street, it is terrific that a world-renowned advertising company – M & C Saatchi – has devised such a positive campaign for all booksellers.”

In keeping with its message about the physical presence of bookshops, the campaign will feature strong branding and a very distinctive prop: a cloth bag with the words BOOKS ARE MY BAG printed on it in capitals in neon orange. These bags will be given to customers by bookshops across the country when the campaign is launched on 14th September. I wasn’t sure about the colour when I first saw it – and I was hugely impressed that Tim Godfray was prepared to spend the whole day wearing a matching T-shirt emblazoned with the orange slogan. However, throughout the Book Fair, I spotted people carrying these bags (the BA gave them out daily) and I concluded that they are very effective indeed. As Patrick put it, “This is the first time anyone has needed sun-glasses when inside the London Book Fair.” I have acquired two of them, one from the BA stand and one from the event, and I shall carry them with pride throughout the summer.

Anyone reading this blog who is interested in knowing more about this, here is your link Books are My Bag to its dedicated website.

I love bookshops!

A London Book Fair 13 seminar about using social networking to create author presence

I cannot miss the opportunity to comment in today’s post on the social networking session yesterday morning at the London Book Fair. First, may I thank the very many people who attended and made the event very special indeed; you were a lovely, attentive audience and we all valued your interest and contributions.

Secondly, I should like to thank Elaine Aldred (@EMAldred, Strange Alliances blog), who very generously agreed some time ago to chair this session and, with her characteristic attention to detail, introduced the panel and provided a succinct summary of the key points arising, as well as modestly managing us and our timekeeping!

I was very pleased to meet and honoured to join my much more experienced social networking fellow panellists, Katy Evans-Bush @KatyEvansBush) and Elizabeth Baines (@ElizabethBaines), and to be able to listen to the social networking supremo, Chris Hamilton-Emery, Director of Salt Publishing (@saltpublishing), all of whom provided different perspectives from my own. However, though we may have addressed in various ways the topic of how to make the most of the best of social networking, I felt that we were un

animous about the terrific value of what Chris called ‘the confluence’ of such media as Twitter, Facebook and personal blogs in creating author presence and profile. I believe that we also affirmed the essential need to be ourselves (however uncomfortable it may initially feel to present our private side, as Elizabeth very pertinently explained) and to interact with the people we ‘meet’ in a genuine way. We shared the view that ramming our books down the throats of our online audience in a ‘hard sell’, as some people do, is counter-productive; it is much better for us to engage with others in discussion of the things which matter to us, such as the business of writing, literature, topical issues and so on. Katy pinpointed the effectiveness of social networking in creating a global family of friends and followers, something we also all felt.

animous about the terrific value of what Chris called ‘the confluence’ of such media as Twitter, Facebook and personal blogs in creating author presence and profile. I believe that we also affirmed the essential need to be ourselves (however uncomfortable it may initially feel to present our private side, as Elizabeth very pertinently explained) and to interact with the people we ‘meet’ in a genuine way. We shared the view that ramming our books down the throats of our online audience in a ‘hard sell’, as some people do, is counter-productive; it is much better for us to engage with others in discussion of the things which matter to us, such as the business of writing, literature, topical issues and so on. Katy pinpointed the effectiveness of social networking in creating a global family of friends and followers, something we also all felt.

All in all, the session emphasised that participation, helping others, reciprocating generosity and showing real interest in people whom we come to know online are crucial to creating a lasting author presence. It is really important that authors recognise that they need to have such a profile; with it, books certainly do sell and, as Chris put it, without it they don’t.

Finally, we all accepted the inevitable consequence of managing all of the personal interactions online: it is extremely time-consuming and we have to find our own ways of handling that; if we succeed, the benefits are very clear to see.

My thanks again to all concerned in what was for me a very memorable occasion.

Shakespeare, a man more sinning?

Recent research, I was amused to read, shows that Shakespeare was fined for hoarding malt and corn and selling it to his neighbours at times of poor harvest. At the time, he was already an established author with (presumably) a reasonable income, so indigence could not have been an excuse. We already knew that in his youth he poached deer and that as an adult he was fined for not attending church. The two latter are perhaps more in keeping with the anarchic streak that we expect from a writer, but discoveries of the Bard’s foibles and failings are always greeted with a sense of incredulity, if not outrage. This is curious, for surely it is illogical to expect the nation’s most profound student of character to have been himself a colourless tabula rasa. Besides, living in Elizabethan England was an uncertain business at all social levels and we know that Shakespeare was not without the type of social ambition that could be fuelled only by money. His acquisition of New Place, a substantial house, would have sent a message to prosperous Stratford burghers that he could claim his place as their equal.

The world seems to require a moral standard from Shakespeare, as if his intellect and wordpower somehow elevate him to a heavenly plane, where there is a writer paradise entirely free from sin, that we may look up to and admire; we don’t seem to require this of other writers in the same way. Byron’s poetry, for example, is not judged by his immorality. So why the sense of shock with Shakespeare? Perhaps it is because we know so little of Shakespeare’s life, so that every new snippet of information about him carries greater weight and significance than if his career were better documented. I do, however, think that it is more likely that it is because he is viewed as a kind of literary god, whose grasp of humanity is superhuman, and as the yardstick by which we judge all our literary heritage; it is unthinkable to ascribe grubby behaviour to such a mighty individual!

However, as a writer of murder stories, I am glad that Shakespeare was demonstrably a sinner and very human. His understanding of and rapport with the realities of human behaviour and character paved the way for the rest of us by creating some of the most eloquent murderers of all time. I’m not sure that a goody two shoes would have been able to manage that.

There may have been criminal lapses in some NHS care, but it’s a crime not to praise the NHS for what it does well.

Earlier this week, I was booked into my local NHS hospital as a day-patient in order to undergo a minor medical procedure. I’ve always had excellent service from the NHS and try to take the trouble to say so each time I use it, as it has had, just recently, a lot of bad press. The irreproachable care that it dispenses 95% of the time often fails to get a mention.

Mine was the first generation to benefit from the NHS from birth. Early memories include solemnly hanging on to the handle of the pushchair when my younger brother was being taken to the clinic. (That pushchair was something else: made of a kind of khaki canvas, with solid metal wheels, it folded up crabwise, so that the wheels lay flat under the canvas. It weighed a ton and had been used by several babies in the family. If they’d had pushchairs in the First World War trenches, I’m sure that they would have looked like this. Apologies for the digression!) One of the best things about the clinic was the unusual, NHS-exclusive foods that it dispensed. These included cod liver oil (which wasn’t nearly as bad as people now make out), tiny intensely-flavoured tangerine vitamin pills and, my favourite, an orange concentrate that could be diluted to make a long drink which was called orange juice. It didn’t taste of orange juice, but it was delicious and I’ve never encountered anything that remotely resembled it since. A slightly later memory is of standing in a queue in the freezing cold yard of the doctor’s surgery with all my primary-school classmates, waiting to be inoculated against polio. The injection hurt, but the nurse was at the ready with a twist of paper containing several brightly-coloured boiled sweets for each child.

When I came back from the theatre this week, the comfort of NHS comestibles immediately kicked in again. A severe young nurse, who was rather old-fashioned (plump, with dark curly hair and a fresh face, she would have made an excellent poster girl for a 1950s nurses’ recruitment drive), forbade me to get out of bed until I had consumed tea and toast. She returned immediately with two doorstep slices of white bread slathered with butter, a cup of mahogany-coloured tea like that my grandmother used to make – I think you can achieve the desired effect only with industrial quantities of ‘real’ tea-leaves and plenty of whole milk – and a packet of three chocolate Bourbon biscuits. Immediately, I recalled the last occasion on which I had seen such a packet of biscuits, also at an NHS hospital. It had been more than a quarter of a century ago, towards the end of my final ante-natal class at St. James’s Hospital in Leeds. Having spent upwards of an hour with several other imminent mothers, alternately lying on the floor like so many beached whales to practise breathing exercises and grabbing each other’s ankles to simulate contractions (what a joke this was only became apparent some time later), we were blissfully interrupted by the tea lady, doing her rounds with mahogany tea and packets of Bourbon biscuits. The latter tasted all the better for being forbidden – we’d all just been lectured on eating the right foods for ‘baby’ and the crime of putting on too much weight – when this no-nonsense lady appeared and made it obligatory for us to tuck in.

I suspect that one of the reasons why the nation takes the NHS so much to its heart is that it has always managed to embrace this ambiguity between what is ‘good’ for you and what forbidden fruits it will allow in order to cheer you up. Another is that the treats themselves have not changed over the years. Doorstep toast, mahogany tea, packets of Bourbons biscuits – they all belong to the relative innocence of the 1960s, when it didn’t take too much to please.

Stuffed as I was with toast, I couldn’t manage my Bourbon biscuits as well, but I asked the nurse if I could bring them home with me and I certainly intend to enjoy them. In spite of what appear to be thoroughly unacceptable lapses in Mid Staffordshire from the very high standards I have always found in evidence in my visits to hospitals, I shall continue to praise the NHS and the homespun comforts that it offers. If someone could rustle up a bottle of that concentrated orange juice, I would give it a blog-post all to itself.

The likes of a blogpost? A crime of expression…

As I’ve admitted in a previous post to having pedantic tendencies, I won’t apologise for them again today. In fact, snowed in and beleaguered by a power-cut as I am and having, at the time of writing, no hot water, no central heating and no means of obtaining hot drinks or cooking food (though mercifully I am sitting in front of a warm stove with a goodly supply of logs to burn and books to read), I have decided to treat myself to a bit of a Saturday rant.

Every so often, an expression that I particularly dislike seems to pop up with alarming frequency in the media. The one that I am thinking of at the moment is ‘the likes of’. It has been around for a long time and has always made me shudder. I associate it very much with certain annoying adults of my childhood who both used it and also perpetuated other hateful stereotypical sayings, such as ‘Had you thought of that?’ (thus indicating none too subtly that the speaker regarded himself or herself as of superior sense and intelligence) or, most heinous of all to me, ‘Yes, but…’ to any helpful suggestion that I might have ventured to make.

However, I had believed that use of ‘the likes of’ had been steadily waning in popularity for at least three decades. I had not encountered it much at all for ten years or so, until January this year. Now it seems to have resurfaced with a vengeance, like a virus that has lain dormant and suddenly been exploded back into life by some trick of the climate. The first occasion on which I noticed its resurgence was when Bradley Wiggins made his winning appearance at the BBC Sportspersonality of the Year Awards and said that he had never imagined that he would be standing there on stage with ‘the likes of’ the Duchess of Cambridge and the others with her. Among the rash of new incidences that have cropped up since then, a recent review by a well-known literary columnist referred to ‘the likes of Kafka’ and yesterday a newscaster on Radio 4, announcing bad weather warnings, spoke of ‘the likes of Oxford and Wales’.

Aside from the fact that to me it sounds more than a little derogatory, what exactly is meant to be conveyed by ‘the likes of’? Whom else besides the Duchess herself (pace Hilary Mantel) could possibly be described as ‘the likes of’ the Duchess of Cambridge? Who is the ‘like’ of Kafka, that most uncompromisingly individual of authors? Where are ‘the likes of’ Oxford and Wales, two distinctive geographical places, one a city, the other a country, which are not remotely like each other and neither of which, to my knowledge, resembles anywhere else? Is the expression supposed to liberate some kind of imaginative power in the listener, by inviting him or her to supply his or her own references to fill the implied gap? Thus I might think ‘this is like Kafka and Jeffrey Archer’ or you might think ‘this is like Oxford and Orkney’: all very confusing and not at all helpful.

What I’m attempting, I suppose, is to understand why the phrase exists at all. What does it add to the point that is being communicated? If Bradley Wiggins had said, ‘I never expected to be standing on stage with the Duchess of Cambridge and…’, would anything have been lost by the omission of ‘the likes of’? Would he not actually have come across as more gracious and complimentary? If the newscaster had simply said, ‘There are severe weather warnings for Oxford and Wales’, would our understanding of the message have been impaired by his not having included the rogue phrase?

Sometimes I’m a fan of redundant phrases. They can make what we say more graphic, more picturesque, even more nuanced and sensitive. But ‘the likes of’? Spare me! If the likes of you and me agree to boycott this nasty conjunction of three little words, perhaps we can start a fashion that will spread throughout the English-speaking world until, like smallpox, the expression has been completely eradicated. ‘Yes, but,’ you might say colloquially, ‘one day the likes of Bradley Wiggins is sure to emerge again. Had you thought of that?’