Fight for your rights and be free!

Many authors are mystified by – and sometimes afraid of – the seemingly arcane world of rights. Interestingly, as internet books sales have boomed and the RRP is merely a guide to how much the book will cost, many readers also feel frustrated by their lack of understanding of rights and sometimes ask if authors are getting a good deal. In this post Lynette Owen, editor of Clark’s Publishing Agreements, explains what rights are and how they should be used.

In the world of publishing, rights – sometimes referred to as subsidiary rights – can be something of a mystery to authors (and indeed to some staff working in other areas in publishing houses). Rights are ways of exploiting the intellectual property in a literary work by licensing the content – perhaps to be published in an overseas market, published in translation, or used as the basis for a stage, television or film adaptation. These rights normally belong in the first place to the author (and perhaps also to the illustrator where relevant) who may then choose to specify that all or some categories of rights are handled by their literary agent or their publishing house. The share of revenue paid to the author from licensing arrangements will be specified in the contract between author and publisher; for deals handled by a literary agent, an agreed rate of commission will be paid to the agent.

As General Editor of Clark’s Publishing Agreements: A Book of Precedents (11/e, Bloomsbury Professional, January 2022), I receive mixed feedback on how the contractual precedents are used. Many small publishers use the downloadable templates verbatim, whilst larger publishers may want to tailor the wording to reflect company practice in terms of royalty models, warranties and indemnities, accounting dates etc. Some publishers incorporate selected wording from the Clark templates into their own contracts.

How an author chooses to grant control of rights in their work will depend on individual circumstances. If represented by an agent, the agency may make separate publication arrangements for separate markets, e.g. the UK and Commonwealth with a British publisher and separate arrangements with a US publisher. The agency may have specialist departments to handle translation rights or film and television rights, so those categories would be withheld from the English language publishing house/s. If no agent is involved, much will depend on the geographical territories granted to the publisher and the resources of the publishing house to exploit rights, something authors should discuss before contracting. These days, many larger publishers will expect e-book and audiobook rights to be included as part of their primary publishing rights. If some categories of rights are withheld from the publisher, authors do need to consider carefully whether they have the time and expertise to handle rights negotiations and contractual and accounting arrangements themselves.

The role of a literary agent is to act in the best interests of the authors they represent; however, not all authors are represented by an agent and it is rare for agents to operate in the areas of educational, academic and professional books, where contracts tend to be directly between author and publisher. If authors are concerned about the fairness of some elements in the publisher’s contract, they should first clarify any points with their editorial contact in the publishing house, who should be able to explain the reasons behind the contractual requirements. It is also worth noting that the Society of Authors can offer advice to member authors, although they probably do so more frequently for trade (general) authors than for educational and academic authors whose contracts usually differ from trade contracts to reflect different market conditions. Any formal legal advice on a publishing contract should be sought from a firm specialising in intellectual property matters.

I first joined the publishing industry immediately after graduating from London University, starting work in the London office of Cambridge University Press, and came to work in their rights department almost by accident – rights work was little known as a career path back then. In 1973, I moved to set up a rights department at Pitman Publishing, then spent a year at trade publisher Marshall Cavendish before joining the multinational publisher Longman Group Ltd (now Pearson Education), latterly as Copyright Director. I was fortunate to be able to travel extensively to sell rights, both at international book fairs but also on sales trips and publishing delegations – educational and academic publishers were early entrants to challenging markets such as the former Soviet Union, central and eastern Europe and mainland China. Space here precludes recounting many strange experiences in those markets, some of which I covered in my recordings for the British Museum Book Trade Lives project! Since 2013, I have worked as a freelance copyright and rights consultant, providing advice on rights and contracts to smaller publishers and also running training courses for publishers and degree students on rights in the UK and abroad. In addition to my work on Clark’s Publishing Agreements, I am also the author of Selling Rights, now in its eighth edition (Routledge, 2019) – as far as I am aware, the only book on the subject.

I think the most attractive aspect of working in rights is the opportunity to meet a wide range of publishers from all over the world and build up long-term relationships with them; a great deal of rights business hinges on personal relationships. It is also challenging and hugely rewarding to negotiate rights deals on behalf of authors and to tie up those deals in legally sound licence contracts, fair to both parties. By contrast, perhaps the most frustrating aspect of rights is that senior management in some (but not all!) publishing companies still do not recognise the value of the rights function, both in terms of generating revenue for authors and publishers but also in terms of the PR value derived from broadening access to publications through licensing.

My rights-related tips to authors would be:

- If you have a literary agent, talk to them about rights possibilities and be prepared to assist with promoting rights if required.

- If you work directly with a publisher, find out how they handle rights and make contact with their rights staff.

- But do try to be realistic in your expectations for rights deals – not every book is a candidate for the silver screen!

For publishers, my tips would be:

- Time and effort expended on the promotion and sale of rights will produce results, even for smaller publishers with limited resources, and will enhance expertise.

- Rights selling depends on building long-term relationships with compatible publishing partners – these take time to establish.

- To publishing management – recognise the importance of a rights operation, both in terms of revenue and PR value to author and publishing house alike.

© Lynette Owen

In tomorrow’s post, Hannah Deuce, Marketing and PR Manager for Bloodhound Books, describes how she works with authors.

The author’s journey: Fraser Massey, established journalist and aspiring crime writer

Fraser Massey has recently completed Whitechapel Messiah, a crime thriller yet to find a publisher. Written in the first person, it’s about an ambitious news reporter who needs to learn that there are grim consequences for not telling the whole truth when writing headline-grabbing front page stories. The protagonist’s misrepresentation of what happened in a street battle between police and protestors in Whitechapel, where a woman died while being arrested, provokes further riots across the country causing widescale destruction and more deaths. To try to put things right, he investigates the reasons for the woman’s death and finds himself infiltrating a sinister religious cult who believe they’ve found the new Messiah.

Fraser is a journalist by profession. He studied Communications at the University of Sunderland and has worked for several regional and national newspapers, including stints as a feature writer for The Times and as a showbiz reporter on the Daily Mirror, as well as writing a weekly column for three years on the Radio Times. He loves books and says his flat is groaning at the seams. His favourite bookshop is Goldsboro Books in London’s Covent Garden.

Because he wanted to try to write fiction, Fraser enrolled in a course run by the Guardian with the strap line ‘Learn to write a crime novel in a weekend’. He says that, unsurprisingly, he didn’t achieve this improbable feat, but the course gave him a taste for learning more, so he studied on the MA in Creative Writing course offered by City University in London. To gain the award he had to write a whole novel. This was his first attempt at completing a full-length work of fiction and it was proficient enough not only to qualify for the MA but also to attract the attention of several agents.

But none followed up on their initial interest. A slush-pile reader for one agency later explained to him that his choice of genre for that book – it was a western – probably counted against him. “Westerns are so notoriously difficult to sell in Britain that most bookshops don’t even have a shelf displaying them,” he was told.

To avoid making the same mistake twice, he enrolled on a short course run by Curtis Brown, the well-known literary agency, hoping to learn how to write a more commercially appealing novel. It was while there he began writing Whitechapel Messiah.

While the book was still in its early stages, an early draft of it was shortlisted for the Capital Crime Festival New Voices award, although on the night the prizes were handed out it was pipped at the post.

Encouraged by this near success, Fraser decided that entering competitions were the way forward if he wanted to get noticed as a writer (which is how I came into contact with him – I have run several Nanowrimo competitions on behalf of publishers).

Challenged on the value of creative writing courses – opinion on these seems to be polarised, with some people thinking they are indispensable and others disliking them – Fraser says they have been useful to him. They have taught him how to read books as a writer, to learn from other authors. At present, he is reading the works of female writers, to study how they describe women – and men, too. Reading other novelists – he reads at least one book a week – has also helped him to write dialogue. For the City course, he was given a book to study and a number to call to interview the author – and he got Lee Child! He says Child was very helpful – although he did tell him to abandon the creative writing course and “learn how to do it yourself” (much to the annoyance of the tutor!).

As I am familiar with Fraser’s writing, I offered the criticism that sometimes the prose is surprisingly inaccurate for someone who has earned their living from writing. He agreed and said that one of the hazards of journalism is that the journalist gets the story down as quickly as possible and then passes it to a sub-editor for polishing. He has therefore developed a few bad habits that he is now trying to eradicate.

Fraser has many tips to offer other would-be crime writers. Here are his top 5:

- Join a writers’ group. It’s good to have people around you to offer advice when you run into problems; and anyway writing is otherwise too solitary an occupation.

- Focus on structure. If your plot doesn’t run smoothly, you run the risk of readers’ getting bored and giving up on your book. As Mickey Spillane said, “Nobody reads a book to get to the middle.”

- Find regular time in your day to devote to writing. This includes time to revise what you’ve written today and to think about what you’re going to write tomorrow.

- The crime novelist Claire McGowan taught me: “Premise (the fundamental idea behind your plot and its unique selling point) is the most important thing in publishing today.” I won’t even start writing another book until I’ve worked out a cracking premise first.

- Writing a good synopsis is one of the most daunting tasks. Next time, I’m going to map out the synopsis before I sit down to write a word of chapter one.

This is all great advice. Each one of these tips involves exercising good discipline as a writer. It’s easy to jump too soon into the actual writing: as Fraser says, “Writing is the bit I enjoy most, so I don’t want to be distracted by having to worry whether my plot works when I’m immersing myself in the narrative voice.”

If you are a publisher and interested in taking a look at Fraser’s novel, please contact me at christina.james.writer@gmail.com .

Tomorrow the post will be by rights expert Lynette Owen, on how authors should approach copyright.

National Crime Reading Month and www.christinajamesblog.com

The Crime Writers Association (CWA) and the Reading Agency have built on their brilliant lockdown idea of designating June as Crime Reading Month (CRM). This June, crime writing of all kinds will be celebrated in bookshops, schools, libraries and museums and at special events. CWA members are all encouraged to engage in some kind of activity to celebrate crime writing and reading, however small – it could be something as simple as encouraging a local library or bookshop to mount a crime fiction display – or large – the festivities culminate with the announcement of this year’s Daggers Award winners. More information about individual activities and events can be found at Events – National Crime Reading Month. It is worth checking this site every day, as exciting new projects are continually being added.

I think CRM is a very exciting concept and I am planning to participate by offering a new blog post every day during June on some aspect of crime writing, reading or publishing. Most of the posts will take the form of interviews with people prominent in these areas and I have many great interviews already lined up: for example, with Richard Reynolds, the doyen of booksellers specialising in crime fiction; Dea Parkin, the secretary of the CWA; and Lynette Owen, the distinguished editor of Clark’s Publishing Agreements, as well as authors, book lovers, bloggers, librarians, publishers, policemen and more booksellers. I have been invited to take part in several events myself and shall be covering these, too. There are still a few spaces left in the latter half of the month, so, if you would like to take part in an interview for the blog, please let me know.

I’ll write one or two posts about certain aspects of my writing. Questions that I have been asked are: ‘Why do your books describe the towns and villages of Lincolnshire as they were when you were growing up, even though the novels themselves are set in the present?’ and ‘What is the fascination that Lincolnshire still holds for you as an author, when you say you moved away many years ago?’

I’ll pick up on this later in the sequence. In the meantime, I do hope you will find time to follow the posts and enjoy them. The series will begin tomorrow with the Richard Reynolds interview. Why have I started with a bookseller? The post itself explains.

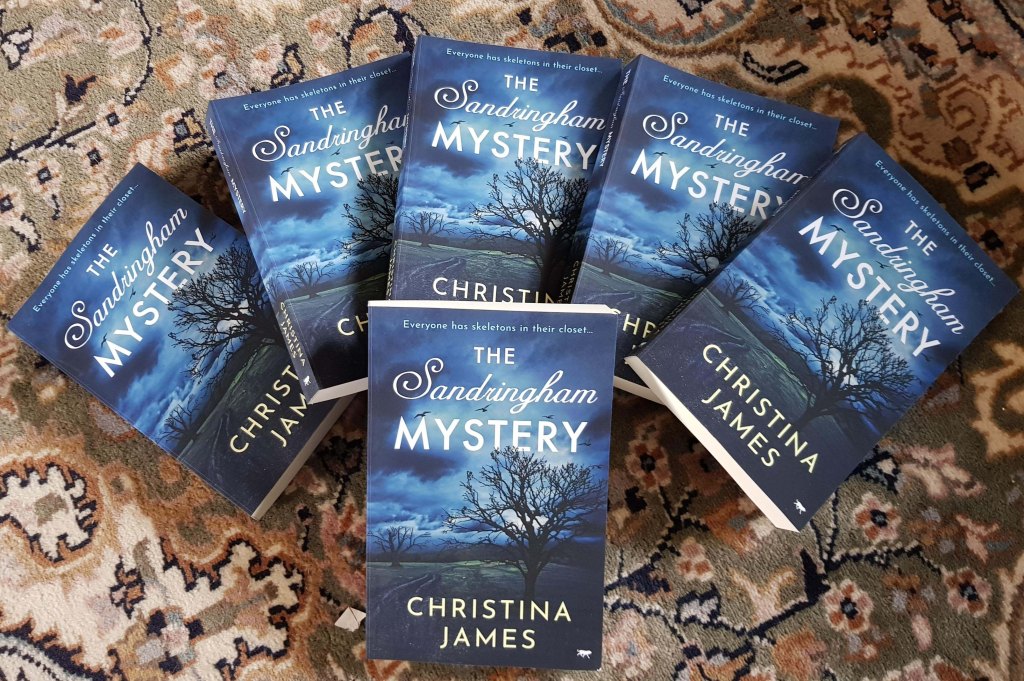

The Sandringham Mystery and some personal memories of places and people with a part to play in its creation

When I was a child, the motor car was the ultimate status symbol. Families aspired to own one and felt they had ‘arrived’ when the car did, however shabby or humble it might be.

Our next-door neighbours, Harry and Eileen Daff, were the first in our street to bring home a car. Theirs was a forties Morris with running boards which looked as if it belonged on a film set, but that made it yet more glamorous in the eyes of the local children. The Daffs went out for Sunday afternoon rides in their car. Mrs Daff – ‘Auntie Eileen’ – was always promising to take me, too, but the invitation never materialised.

My father acquired our first car about three years afterwards, when I was nine. It was a two-door Ford Popular which we nicknamed ‘Hetty’. I can remember the registration number: it was HDO 734. Hetty, like the Daffs’ Morris, was not only second-hand but practically vintage. My father had saved hard to afford her and had still needed a loan from my miserly – but loaded – Great Uncle David to complete the purchase.

Great Uncle David lived – indeed, spent his every waking moment – working in the convenience shop in Westlode Street which he had inherited from his parents despite being their youngest son, presumably because he had scoliosis and was considered ‘delicate’. My paternal grandmother kept house for him. They were only a short bike ride away.

My mother’s mother, however, was the paid companion of a very old lady and lived in Sutterton, nine miles distant, which meant that in pre-Hetty days visits had to be accomplished by bus. It was usually she who visited us, invariably spending the morning of her day off shopping in Spalding and then walking to ours for lunch. Post-Hetty, we were able to make more frequent visits to Sutterton. However, I was still sometimes allowed to travel there alone on the bus. It was nearly always on a damp, foggy day when the sun never broke through the Fenland mists.

The house she lived in was the house I have called Sausage Hall in The Sandringham Mystery. It was a big, gloomy red-brick house in considerable need of repair. Sometimes she occupied the breakfast room when she had visitors, but her natural habitat was the kitchen with its adjoining scullery, in both of which roaring fires were kept burning night and day throughout the winter months. The kitchen fire had a built-in oven in which she would bake perfect cakes. Lunch would be tinned tomato soup and bread, followed by a big hunk of cake. Cherry cake was my favourite.

Her employer’s name was Mrs James. My grandmother always referred to her as ‘the old girl’. Mrs James’s first name was Florence and she was one of a large family of sisters, the Hoyles, who had been brought up in Spalding in extreme poverty. One of the sisters still lived in what could only be described as a hovel in Water Lane and occasionally, after one of my visits to Sutterton, I would be sent round with cake or chicken. Miss Hoyle never invited me in. She would open the door a few inches, her sallow face and thin grey hair barely distinguishable from the shadows of the lightless cavern behind her, and reach out a scrawny hand to take what I had brought, barely muttering her thanks before she shut the door again.

My grandmother, also the eldest of a large family of sisters, despised the Hoyles. Mrs James was not exempt. My grandmother’s father had been a farm manager, employed by a local magnate. He was a respectable, hard-working man of some substance in the community, unlike the allegedly feckless Mr Hoyle. According to my grandmother, Florence had ensnared Mr James with her pretty face, but that did not excuse her humble beginnings.

Florence, long widowed, had taken to her bed, for no other apparent reason than that she was tired of the effort of getting up every day. My grandmother delivered all her meals to her bedroom and sometimes sat there with her. When I visited I was expected to call in to see her before my departure. I never knew what to say. She would extend a plump, soft white hand from beneath the bedclothes and offer it to me. I’d shake it solemnly. Once, when I’d been reading a Regency novel, I held it to my lips and kissed it. She was momentarily surprised – I saw the gleam of interest in her eyes before her spirit died again.

Mrs James’s sons, both middle-aged gentlemen farmers, also performed duty visits. My grandmother and I were expected to call them ‘Mr Gordon’ and ‘Mr Jack’. In The Sandringham Mystery, Kevan de Vries, head of the de Vries empire, has his staff call him ‘Mr Kevan’. I lifted the idea from my experience of the two James brothers. I was about nine when I met them and could identify condescension when I encountered it.

Hetty broadened our horizons immeasurably. Instead of going out for bike rides at weekends, we drove to local beauty spots – Bourne Woods, the river at Wansford, Barnack – and sometimes on nice days even further afield, to Hunstanton, Skegness and Sandringham.

Sandringham, the Queen’s Norfolk estate, consists of many acres of forest, most of which were already open to the public, though the house itself wasn’t. It was possible to visit the church. Both local people and visitors would wait outside the wall beyond the churchyard for glimpses of the royal family when they were in residence. I saw Princess Margaret once. She had the most astonishing violet-blue eyes.

I associate Sandringham particularly with the clear bright cold of Easter holidays and the drowsy late-summer warmth of blackberrying. The blackberries there were enormous and my brother and I would scratch the skin on our arms to ribbons trying to reach the best ones. Parts of the woods were deciduous, but the blackberries seemed to flourish in the areas where the pine trees grew, planted in squares and divided up by trails (‘rides’). When I was writing The Sandringham Mystery, I remembered vividly a clearing in the woods that had been made by the crossroads of two trails. In the novel, it is here that the body of a young girl is discovered, the start of a police investigation that not only reveals why she was murdered, but also uncovers some other terrible murders that took place in the past, in Sausage Hall itself. The Sandringham Mystery is published by Bloodhound Books today. I hope you will enjoy it.

Fact and fiction; fiction and fact – and ‘faction’ and ethics!

I spent the weekend reading a novel (no, not the one above, which I’ll mention later) that described a series of events with which I am personally familiar, although they happened more than ten years ago and my role at the time was very much that of bystander – I didn’t know most of the facts until some years later. I emphasise the word ‘facts’ – I’m not talking about a lookalike situation here. I didn’t know there would be any kind of personal connection when I bought the book. It is by an author whose work I have read before – mainly in the form of journalism – and I was curious to know how she had shaped up as a novelist.

As I embarked on the novel and the narrative unfolded, I was stunned to realise that this was an undisguised account of those very events. The only subterfuge the author had used was to give the main characters different names – though names very much in keeping with the originals. She didn’t, for example, rename a Charles ‘Sidney’ or a Joanna ‘Edith’.

The novel tells the story of a love triangle. The three protagonists are a married couple and the man’s colleague, with whom he embarks upon an affair. Nothing special about that – it’s one of the oldest plots in the world. Think Jacob, Leah and Rachel or Guinevere, Arthur and Lancelot. Think The English Patient. This novel’s uniqueness lies in the detail: the venue and circumstances of the lovers’ first tryst, the man’s family situation, the place to which he takes his by-now mistress for a holiday, his death by suicide. Yes, indeed – the man commits suicide, unable to extricate himself from the mess which he has made of his life. And my point is: none of this is fiction.

Let me wind back to my own very tangential participation in this tale. I have never met the author, who is the mistress in the triangle. I have also never met the wife. As far as I know, neither is aware of my existence. I knew the husband as a professional acquaintance during the last months of his life – although of course neither he nor I knew that they were. I had just set up a new freelance business and I was working on a project with him. Out of the blue, his PA called me and told me he had “died suddenly”. I didn’t know it was suicide until some years later, when I worked on another project with another of his former colleagues, who had by now moved to a different company. We talked about his death and she described to me more of the details that led up to it.

As a result, and belatedly, I am much more clued up now about the course of events than I was immediately after they took place; and what strikes me very forcefully is that most of what I have just read in this ‘novel’ is not fiction at all. Except for the passages that conjecture what the main actors were feeling (including the wife, who, unsurprisingly, is not portrayed with much sympathy until the end), it is a blow-by-blow, more or less verbatim account of what actually happened. It may very well have been cathartic – and even lucrative – for the author, but what about the emotions it will have triggered in the other players in the story, particularly the wife? How could she have felt when she realised the hugely distressing events that had changed her life forever had been dragged into service as ‘fiction’? What about the two sons, now young men, who were teenagers at the time?

I have asked these questions rhetorically, but I am genuinely interested to know what others think. I am aware that authors have sometimes been taken to court for writing about characters who bear too close a resemblance – or even the same name – as someone who exists. For example, the first printing of Richard Adams’ The Girl in a Swing (great novel if you don’t know it) was recalled after an acquaintance of his objected to his use of her name and he had to change the name. Conversely, I know some authors make fictional use of their own experiences but relate them to characters who are quite different from the originals. None of my own characters is recognisable as an individual who truly exists, though I have observed and written about unusual characteristics in people I know to make my characters more interesting.

When does something billed as fiction actually become ‘faction’ – and how much should an author be allowed to get away with, not just legally, but also morally speaking?

I have chosen not to name the title of the novel I’ve been discussing here or identify its author. I do not want to add more oxygen to the publicity it has already received. I don’t wish to sound sanctimonious, but reading this book has made me feel very uncomfortable indeed.

The Physics of Grief

It is my privilege to have received an advance copy of The Physics of Grief, by Mickey J. Corrigan. Mickey is an author whose work I have long admired, someone who brings wisdom, humour and gracious writing to both the mundane and humdrum grind of daily life and to the truly horrific events that occasionally engulf human beings. This book is published today, April 22nd 2021, by QuoScript.

The Physics of Grief is classic Mickey. The protagonist of the book, Seymour Allan, is initially only a semi-likeable character to whom the reader is drawn – if at all – by sympathy for his situation. He is living in a retirement complex because poverty, rather than old age and infirmity, has made this a necessity. He is broke; he is lonely; he is full of self-loathing; and he lives alone, save for a stray cat he has adopted. (Note from a cat lover: few characters in novels who love cats are entirely bad.)

Seymour’s luck changes when he is accosted in a café by the mysterious and enigmatic Raymond C. Dasher. For me, Dasher is the most intriguing character in the whole novel. Is he even a real human being? There clings about him something of the supernatural, reminiscent perhaps of Hermes Diaktoros, the “fat man” of Anne Zouroudi’s crime novels set in Greece (surely intended as an earthly manifestation of Zeus?), who comes and goes like the Cheshire Cat, or of the shade of the grim reaper who lurks in Muriel Spark’s Memento Mori, having a voice but never a physical presence.

But Raymond C. Dasher is both corporeal and articulate. He’s not particularly likeable, either: he has a dangerous sense of humour that verges on the cruel and he treats his employees – or perhaps I should say employee, because Seymour never meets any of his colleagues, another puzzle – with casual if paternalistic contempt. Nevertheless, the poverty-stricken Seymour does agree to become an employee of Dasher, as a professional griever (apparently this is genuinely a way of making a living in several countries today – not entirely surprising, as paid mourners, or ‘mutes’, were a definitive part of the grief landscape in Victorian Britain, too).

Corrigan has great fun while portraying Seymour at work, as he uncovers the back-story behind each of the deceased who, without being able to muster a respectable number of personal mourners, has left cash to pay to plug the gap at the funeral with “extras”. And whose funerals are they? You’ll be enmeshed!

However – and with a few hiccoughs at the start – Seymour begins to take it all in his stride… with what effect on himself? And how is he personally affected? What lies in his back-story? Corrigan’s skill plays delicately with the reader’s reactions to this man.

Funny, sad, ambiguous, profoundly philosophical yet grounded in the reality of the everyday, extremely erudite about the customs of death (but wearing its erudition lightly), The Physics of Grief is a hauntingly beautiful novel about people and why they do what they do – until they die. And Corrigan also manages to suggest without any hint of religiousness, that even then – perhaps – death is not the end. This is a crime novel with a labyrinth of twists, its originality breath-taking. If you are looking for a mesmerising book to read this spring, you can hardly do better than to invest in The Physics of Grief.

Justifiable homicide

De Vries, the ninth DI Yates novel, will be published soon. As I mentioned in a previous post, it is the sequel to Sausage Hall, although each can be read independently of the other.

De Vries sets out to explore several themes: Why do some people become obsessed with discovering the truth about who their parents are, even at the risk of putting themselves in danger or losing their liberty? Can murder sometimes be justified? And, perhaps a little more whimsically, can buildings hide secrets and even, in certain contexts, develop personalities of their own?

In a future post, I’ll take a closer look at the mystery of parentage. For now, I’d like to consider the second of these themes. Wishing to find out more about whether murder can ever be excused, I looked up the term ‘justifiable homicide’. Unsurprisingly, I discovered that in different countries there is quite a range of legislation ‘allowing’ murder (i.e., not prosecuting the perpetrator). Internationally, the most frequently invoked law is one that absolves the murderer of blame if s/he killed while fearing for her or his own life, or the life of someone else in the immediate vicinity. In other words, the murder has been committed in self-defence. However, the precise definition of what legally constitutes self-defence is often unclear. For example, English law allows someone to exert only ‘reasonable force’ when defending property from an intruder, even if the intruder is trespassing in the middle of the night and the householder claims that s/he was terrified. The well-publicised case of Tony Martin, who shot dead a teenage boy and injured his twenty-nine-year-old burglar companion when they broke into his remote farmhouse in the early hours of one morning in the year 2000, remains controversial. Martin was convicted of murder, later downgraded to manslaughter. He served three years in prison before being released. Twenty years on, public opinion is still divided on whether he should have been convicted at all, but his conviction was the result of careful application of the law. The plea of self-defence therefore seems to depend on a number of factors, including the circumstances of death, how the law may or should be interpreted, the verdict of the jury if the perpetrator is taken to court and, finally, the views of the presiding judge.

Some countries allow or condone types of killing that others would not hesitate to regard as murder. Abortion and euthanasia are allowed by some western jurisdictions, condemned as murder by others. So-called ‘honour-killings’, while they may still be against the law, may attract lower sentences than other kinds of homicide in the countries where they are most commonly practised. (I take a closer look at honour killings in Rooted in Dishonour.) Perpetrators of ‘crimes of passion’ – i.e., murders committed in the heat of the moment, usually against a partner or spouse who has been caught ‘cheating’ or his or her lover – may sometimes be judged leniently, even sympathetically, especially in Latin countries, and a much-reduced sentence consequently handed down.

Whatever one’s stance on this, the logic that dictates that not all murders are equal when it comes to assigning culpability is not hard to understand, even though it is often controversial. But what if the murderer were under no particular pressure when s/he committed the murder? Would it make any difference to the degree of culpability in terms of, say, such a (possibly extenuating?) circumstance as being unexpectedly accosted – perhaps at home – by someone who might not have been at that moment an obvious direct threat, but who had previously inflicted personal – or close-to-personal – harm on him or her? And what if the victim were a totally reprehensible character with no counterbalancing virtues whatsoever? Could the case ever be made for letting the murderer of such a person go scot free, with his or her crime condoned or even tacitly approved by the authorities?

That was the conundrum I had to address when I started to write De Vries.

De Vries: the new DI Yates novel. Writing a sequel

De Vries is the sequel to Sausage Hall, the third in the DI Yates series and among the most popular. It will be published in March. It is indelibly etched on my memory as having been written during the first year of COVID. I’m sure many other writers will have particular memories of what they wrote in 2020.

Readers of Sausage Hall have been asking for a sequel ever since it appeared in 2014. I have found their enthusiasm uplifting and should like to take the opportunity to thank them for it. As soon as Sausage Hall was published, I knew I would write its sequel one day, because the story of Kevan de Vries is far from finished when it ends. Seven years after the curtain went down on de Vries, now exiled to his luxury home in Marigot Bay, it seemed the time was ripe, not least because the seven-year gap features strongly in the plot and is instrumental in deciding de Vries’ fate.

All the DI Yates novels prior to De Vries are standalone. Although the same central characters appear in all of them and some of the minor characters feature in more than one, De Vries was my first attempt at writing a novel whose plot depended on the plot of an earlier book. After giving this a great deal of thought, I decided that I wanted De Vries to work as a standalone novel as well as a sequel – I always feel those authors who expect their readers to read novels 1 – 8 in order to understand novel 9 are cheating. This presented some interesting challenges which I hope I have managed to address successfully, mainly through the use of ‘need-to-know’ tasters. There are snippets of information about what happened in Sausage Hall dotted throughout De Vries – enough, I hope, not to fox or bore the reader – without spoiling Sausage Hall for those who come to it afterwards.

I’ve previously told readers of this blog how my eagle-eyed daughter-in-law picks me up on discrepancies of fact and characterisation between the novels. Spotting and eliminating such errors seemed even more vital this time. She and my editor both re-read Sausage Hall before embarking upon De Vries and I re-read it several times myself – the first time I have read one of my novels all the way through again after it was published.

As it happens, I remembered the plot and characters of Sausage Hall quite accurately, more so, perhaps than some of the more recent DI Yates novels. Nevertheless, re-reading it was an unusual experience because it also reminded me vividly of the specific occasions on which I worked on certain chapters. For example, it was during one of many court adjournments when I was doing jury service at Sheffield Crown Court that I read of the links to Lincolnshire of a famous historical character that gave me the idea for the sub-plot; I was on holiday in Germany when I started writing about Florence Hoyle’s journal. The German holiday house was on a farm in the Munsterland and I remember sitting at the kitchen table with my laptop, the brilliant sunshine streaming through the open door. (Less edifyingly, I was also eating banana cake.)

De Vries himself is one of the most complex characters I have tried to create. He’s not exactly likeable, but he is charismatic; the reader feels sympathy for him because he’s suffered more than his fair share of misfortune – but he brought much of it on himself. Is he a murderer, or has he been framed? I won’t say any more, because I don’t want to spoil it if you’re interested!

I don’t have the finished jacket for De Vries yet, but I will post it on this blog as soon as I can. I’m thrilled with it – it’s an original sketch by Sophie Ground, a very talented artist friend and daughter of my friend Madelaine, herself also an accomplished artist.

I’m also delighted that all the Yates novels except Almost Love – which I’m rewriting; it will be back again in the autumn – are now published by QuoScript, a vibrant new publisher specialising in crime and YA fiction.

I may not have the jacket yet, but I can share the blurb from the back cover. I hope you find it intriguing!

Wealthy businessman Kevan de Vries returns to the UK after an enforced absence, travelling incognito and taking up residence at ‘Sausage Hall’, his ancestral home in Sutterton – secretly, because he must evade being questioned by DI Yates about the disappearance of Tony Sentance seven years previously. Sentance’s sister Carole persistently lobbies the police to have her brother declared dead so she can inherit his estate. She believes de Vries murdered Tony.

De Vries knows he risks imprisonment by coming home, but he’s obsessed with learning his father’s identity, never disclosed by his mother.

Agnes Price, a young primary teacher, becomes increasingly concerned about the welfare of one of the children in her class. Leonard Curry, a schools attendance officer, is sent to investigate, but is attacked. Someone frightens Agnes when she is walking home one night. Shortly afterwards, Audrey Furby, Curry’s niece, disappears…

De Vries is the sequel to Sausage Hall; each novel can be read independently of the other.

Bloomsday

Today is Bloomsday, June 16th, the date that James Joyce renders unforgettable in Ulysses. Ulysses was finally published in 1922, but the novel celebrates the day in 1904

that Joyce first met his long-term (and eventually ‘legal’) common-law wife, Nora Barnacle, who was then working as a chambermaid in a hotel in Dublin. Since I first read the novel in the 1970s, I’ve always quietly celebrated Bloomsday when it has come round each year and still enjoy dipping into Joyce’s account of the perambulations of Leopold Bloom in Dublin on this day. I’ve written about it before, too, but today I have a new dimension to add, something I’d forgotten about for decades.

One of my Covid-19 lockdown projects has been to ‘bottom’ my study and sort through all the books and papers living there. I’ve almost completed this task. Sometimes it has been stressful: I knew I’d have to be ruthless and select some items for recycling or other forms of disposal and I’ve done so, discarding items that logic dictates I will never truly want to use or look at again, despite the happy memories they inspire and the tug of my hoarding instinct..

Many things remain sacrosanct, however, including some discoveries that have surprised and delighted me. Among these is a privately printed guide to the Martello tower that Buck Mulligan, the first character to appear in Ulysses, lives in in the novel.

A foolscap-sized pamphlet printed on hand-made paper, it is entitled James Joyce’s Tower, Sandycove, Co Dublin and was written by Joyce’s most famous biographer, Richard Ellman, and published in 1969.

I acquired it in the very hot summer of 1976, when it was sent to me by William ‘Monk’ Gibbon, an Irish poet and man of letters – in fact, long before then he was known as the Grand Old Man of Irish letters – whom I had contacted when I was carrying out research on George Moore, an Irish author who lurked on the periphery of the Gaelic Revival. As a young man, Gibbon knew W.B. Yeats, John Millington Synge and Lady Gregory and George Moore, as well as Joyce and Oliver St John Gogarty, the real-life inspiration for Buck Mulligan. When I wrote to him, he was one of the last living links with these writers. He had also kept in touch with ‘George’ Yeats, Yeats’s wife, until her death a few years previously. He told me fascinating anecdotes about all of them and sent me several gifts, including the book about the Martello tower and a hand-written poem of his own, inscribed on a sheet of the same type of hand-made paper as the book. He had written out eighty copies of this, of which the one I have is numbered the fifteenth.

I’m posting a copy of the poem, but, in case some of the words are difficult to read, I’ve also transcribed it.

An Alphabet of Mortality

A’s for Arrival on the arena’s sand

B is our distant Birthright, long forgot.

C are the Cards, dealt deftly, to each man.

D is the Desperation of his lot.

E is for Eagerness, which conquers sloth.

F is our Folly, immense, which drags us down.

G are the hallowed, haloed, laurelled Great,

who scorned Happiness, that tinselled crown.

I the insatiable, insistent self.

J all its Jealousy and petty spite.

K is the coloured Kaleidoscope of our views

and L our longing for more stable sight.

M is the makeshift Madness of most lives.

N is Lear’s ‘Never’ to the fifth degree.

O’s the Occasion, haste or hesitate.

And P? Pride, Prejudice and Pedantry.

Q is the ultimate Query all must ask.

R the much-varied Responses from the dark.

S the great Silence, which puts speech to shame

and T the triumph when men leave this mark.

U is the infinite Universe, where there’s zoom,

when all the lies are dead, for Veritude.

W’s recovered Wholeness, which may yet

give X in the equation exactitude.

Y is for Yearning.

So, having overlooked

The many-lettered joys which, too, have been,

I, at the stake, do now recant and say

The Zephyr of my hopes was sweet and clean.

On the reverse side it is inscribed to me, with the message “to she …who knows that whatever the rest of it may say the last letter of my alphabet is the truest.”

It is dated December 15th 1976, the date of his 82nd birthday; he must have written the poem to celebrate it. He lived until 1987.

As I re-read it, it struck me that this poem contains sentiments that are very relevant for our present times (also his use of the word ‘zoom’ made me smile – he had, of course, no idea that in 2020 it would achieve fame as a brand name for a virtual communication product).

Happy Bloomsday, everyone!

Awakening of Spies: Review

This spy thriller is the impressive first novel of a series planned about Thomas Dylan, who is plunged into ‘security’ work when, shortly after his graduation, he agrees to attend an interview for an organisation that needs a linguist. It is the 1970s. The job, which Dylan accepts, means working for the Defence Intelligence Service (DIS) as a civil servant. He is warned that there is no glamour attached to being part of the DIS, which is poorly regarded by both MI5 and MI6.

A boring future seems to beckon: he is convinced he has chosen – or, rather, fallen into – the wrong career, but he is very quickly sent to Zandvoort in the Netherlands on an undercover operation in which he is set up to fail. However, despite failing as resoundingly as expected, he quickly finds himself on his way to South America on a more important mission. It is to retrieve a device called ‘The Griffin’: ‘Garble-Recognition-Interrogation-Friend-or-Foe-Inboard Nautics – Master Control Unit’. The Griffin is never explained more clearly than this, but a reader well-versed in tales of espionage might assume it to be something like a portable 1970s version of the Enigma machine. All the usual suspects are after The Griffin, from the CIA to British Intelligence to various assorted Russians, Israelis and Arabs, not to mention the South Americans on whose turf the action takes place, some of whom are not South Americans at all, but escaped Nazi war criminals.

The plot is a relatively simple one – the novel tells the story of Dylan’s adventures as he tries to track down The Griffin. Both pursuer and pursued, he is continually trying to figure out which of the people he encounters are really who they say they are and which ones can (or can’t) be trusted. Among them is the intriguing upper-class (anti-?) heroine Julia, whose uncle is (allegedly?) a bigwig in the security services. The narrative is written in the first person, which works well: during the course of the novel we see Dylan progress from a greenhorn apprentice spy to a much more mature operator whose rite of passage has included killing as a duty of his new profession.

What makes this novel stand out, apart from the fact that it is beautifully written, is that it is a spy thriller for grown-ups. The plot may be straightforward but the relationships between the various characters are intricate, their underlying rationale complex; yet despite the welter of detail and counter-detail, the author never makes the reader feel lost or, as so many spy writers do, leaves her or him feeling that the book is teetering perilously close to the edge of credibility. Landers has also accomplished the difficult trick of showing a profound understanding of the milieu which he describes without over-parading his knowledge.

There is some violence in Awakening of Spies, but it is not gratuitous or unduly sensational (I’m mentioning this because I know some of my readers don’t like too much bloodshed). Both death and sex are described in a restrained way – there are no James Bond-type shenanigans. If you’d like to try a good spy thriller without the Boys’ Own escapades, I recommend this novel. And I’m already looking forward to the next one in the series.

Awakening of Spies is published by Red Door Press. ISBN 978-1913062330