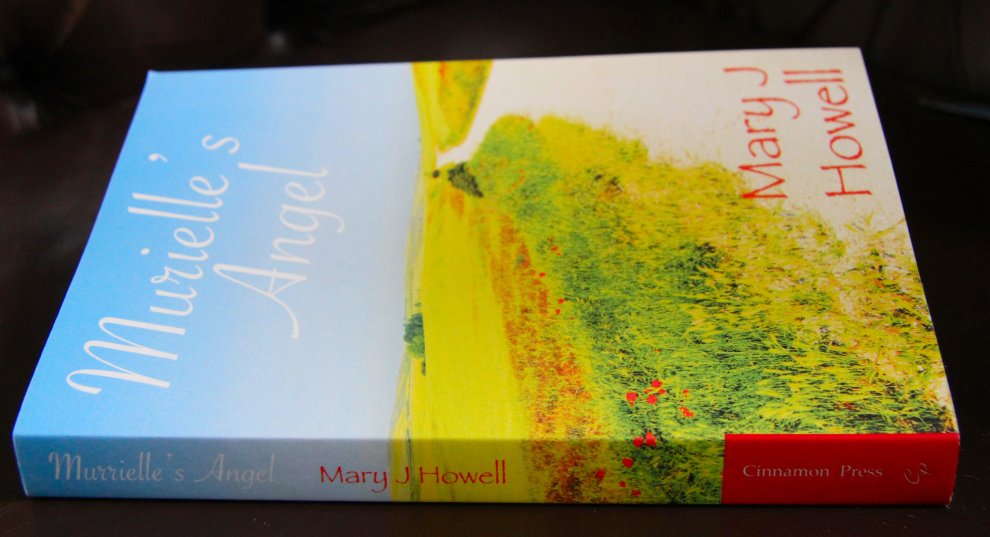

A book to take on holiday… by someone I knew before she became a writer

I first learnt of Murielle’s Angel on the social networks. It is the debut novel of Mary Jane Howell, who is married to one of my husband’s university friends. Though I don’t know Mary Jane well, this is the first novel I have read by someone who was an acquaintance before she became a writer. I have friends who are writers, but that is because they are writers, if I may make the distinction.

It is piquant to read a book by someone whom you not only know but of whose circumstances you also have a little knowledge. The book is about Rosemary, a middle-aged woman who undertakes the pilgrimage of Santiago di Compostella. I am aware that the author herself made this pilgrimage some years ago; there are also other aspects of Rosemary’s personal life that seem to coincide with Mary Jane’s. The novel, however, is described as a fictionalised account of the pilgrimage and I won’t therefore be foolish enough to fall into the trap of assuming that it is thinly-disguised autobiography! I recognise from my own writing that characters can display certain traits or characteristics of people that I know, including myself, whilst remaining fictional creations nevertheless, and I’ve been much amused by readers who’ve told me with great certainty that they ‘knew’ who some of my characters were based on. For example, someone told me that she recognised the original of Henry Bevelton in In the Family. To my knowledge, Henry is entirely fictitious and not based on anyone at all!

Cinnamon Press, its publisher, describes Murielle’s Angel as a modern take on The Canterbury Tales. This is true in the sense that it tells of how a disparate group of people are thrown together, united only by the common purpose of making the pilgrimage; but, unlike Chaucer’s, these pilgrims don’t entertain each other by whiling away evenings and rest periods telling stories; instead, each has a story which the author herself outlines and pursues cleverly, drawing out the threads with admirable economy of detail. There is Stefan, who was brought up in an orphanage and has staked his whole career and possessions on producing a film; Ria, a doctor who is a workaholic seeking to restore some balance to her life and using the temporary separation to re-evaluate her relationship with her partner (interesting parallels and contrasts are drawn between her life and Rosemary’s); Dominic, who is a bit of a chancer and of dubious morality – he is a type, someone we have all met on campsites and ferries, the kind of person who latches on to others in a hail-fellow-well-met sort of way and wants something in return – but for Dominic, too, there is a sad story behind the bravado; then there is a host of minor characters who criss-cross the narrative at intervals – two Canadian nurses, a grotesquely amorous widower, two groups of Germans.

Like Chaucer’s, these modern pilgrims have many reasons for committing to the pilgrimage, none of them overtly religious. Each is trying to ‘find’ himself or herself through the combined abandonment of routine and the privations that the journey entails. There is a strong sexual undercurrent throughout, although only one description of sexual consummation, and that between two minor characters. The author shows that the unfamiliarly liberal circumstances created by a group of strangers being thrown together encourages an often unwelcome removal of inhibitions. Rosemary herself is propositioned on several occasions and is sometimes disgusted, sometimes flattered, by these attentions.

For me, the novel dips briefly about two thirds of the way through, when the combination of apparent moral aimlessness and the dissatisfaction of several of the characters with what they are achieving as pilgrims suddenly tipped me into, if not boredom, at least a bewildered questioning of where it was all leading. But I was too impatient, because it is at this point that Murielle, who has been hovering around the periphery for some time, now takes centre stage. Terminally ill, she is unable to continue further on foot (even with the help of a little cheating on public transport) and takes refuge in the house of a priest. The relationship between Murielle and the priest is exquisitely drawn. He is her spiritual guide as she prepares for death, but also, the author hints delicately, totally (although of course hopelessly) in love with her. It is an act of love that unites all the characters of the novel, as they admire the mural that Murielle has painted on the side of the priest’s house to thank him for his care. Their reaction is unanimously of joy and laughter. It is the priest who teaches Murielle that you owe service especially to those who love you more than you love them. It is a lesson that each of the main characters takes on board, each in his or her own way.

Murielle’s Angel is beautifully written; it is sad, yet uplifting; it is a brilliant achievement, one of the best debut novels that I have read. I’d not heard of Cinnamon Press before I bought it, but it is a publisher whose books I shall look out for now. If you’re looking for some fine writing and an extraordinary narrative to take on holiday, I wholeheartedly recommend this book.