The Sandringham Mystery and some personal memories of places and people with a part to play in its creation

When I was a child, the motor car was the ultimate status symbol. Families aspired to own one and felt they had ‘arrived’ when the car did, however shabby or humble it might be.

Our next-door neighbours, Harry and Eileen Daff, were the first in our street to bring home a car. Theirs was a forties Morris with running boards which looked as if it belonged on a film set, but that made it yet more glamorous in the eyes of the local children. The Daffs went out for Sunday afternoon rides in their car. Mrs Daff – ‘Auntie Eileen’ – was always promising to take me, too, but the invitation never materialised.

My father acquired our first car about three years afterwards, when I was nine. It was a two-door Ford Popular which we nicknamed ‘Hetty’. I can remember the registration number: it was HDO 734. Hetty, like the Daffs’ Morris, was not only second-hand but practically vintage. My father had saved hard to afford her and had still needed a loan from my miserly – but loaded – Great Uncle David to complete the purchase.

Great Uncle David lived – indeed, spent his every waking moment – working in the convenience shop in Westlode Street which he had inherited from his parents despite being their youngest son, presumably because he had scoliosis and was considered ‘delicate’. My paternal grandmother kept house for him. They were only a short bike ride away.

My mother’s mother, however, was the paid companion of a very old lady and lived in Sutterton, nine miles distant, which meant that in pre-Hetty days visits had to be accomplished by bus. It was usually she who visited us, invariably spending the morning of her day off shopping in Spalding and then walking to ours for lunch. Post-Hetty, we were able to make more frequent visits to Sutterton. However, I was still sometimes allowed to travel there alone on the bus. It was nearly always on a damp, foggy day when the sun never broke through the Fenland mists.

The house she lived in was the house I have called Sausage Hall in The Sandringham Mystery. It was a big, gloomy red-brick house in considerable need of repair. Sometimes she occupied the breakfast room when she had visitors, but her natural habitat was the kitchen with its adjoining scullery, in both of which roaring fires were kept burning night and day throughout the winter months. The kitchen fire had a built-in oven in which she would bake perfect cakes. Lunch would be tinned tomato soup and bread, followed by a big hunk of cake. Cherry cake was my favourite.

Her employer’s name was Mrs James. My grandmother always referred to her as ‘the old girl’. Mrs James’s first name was Florence and she was one of a large family of sisters, the Hoyles, who had been brought up in Spalding in extreme poverty. One of the sisters still lived in what could only be described as a hovel in Water Lane and occasionally, after one of my visits to Sutterton, I would be sent round with cake or chicken. Miss Hoyle never invited me in. She would open the door a few inches, her sallow face and thin grey hair barely distinguishable from the shadows of the lightless cavern behind her, and reach out a scrawny hand to take what I had brought, barely muttering her thanks before she shut the door again.

My grandmother, also the eldest of a large family of sisters, despised the Hoyles. Mrs James was not exempt. My grandmother’s father had been a farm manager, employed by a local magnate. He was a respectable, hard-working man of some substance in the community, unlike the allegedly feckless Mr Hoyle. According to my grandmother, Florence had ensnared Mr James with her pretty face, but that did not excuse her humble beginnings.

Florence, long widowed, had taken to her bed, for no other apparent reason than that she was tired of the effort of getting up every day. My grandmother delivered all her meals to her bedroom and sometimes sat there with her. When I visited I was expected to call in to see her before my departure. I never knew what to say. She would extend a plump, soft white hand from beneath the bedclothes and offer it to me. I’d shake it solemnly. Once, when I’d been reading a Regency novel, I held it to my lips and kissed it. She was momentarily surprised – I saw the gleam of interest in her eyes before her spirit died again.

Mrs James’s sons, both middle-aged gentlemen farmers, also performed duty visits. My grandmother and I were expected to call them ‘Mr Gordon’ and ‘Mr Jack’. In The Sandringham Mystery, Kevan de Vries, head of the de Vries empire, has his staff call him ‘Mr Kevan’. I lifted the idea from my experience of the two James brothers. I was about nine when I met them and could identify condescension when I encountered it.

Hetty broadened our horizons immeasurably. Instead of going out for bike rides at weekends, we drove to local beauty spots – Bourne Woods, the river at Wansford, Barnack – and sometimes on nice days even further afield, to Hunstanton, Skegness and Sandringham.

Sandringham, the Queen’s Norfolk estate, consists of many acres of forest, most of which were already open to the public, though the house itself wasn’t. It was possible to visit the church. Both local people and visitors would wait outside the wall beyond the churchyard for glimpses of the royal family when they were in residence. I saw Princess Margaret once. She had the most astonishing violet-blue eyes.

I associate Sandringham particularly with the clear bright cold of Easter holidays and the drowsy late-summer warmth of blackberrying. The blackberries there were enormous and my brother and I would scratch the skin on our arms to ribbons trying to reach the best ones. Parts of the woods were deciduous, but the blackberries seemed to flourish in the areas where the pine trees grew, planted in squares and divided up by trails (‘rides’). When I was writing The Sandringham Mystery, I remembered vividly a clearing in the woods that had been made by the crossroads of two trails. In the novel, it is here that the body of a young girl is discovered, the start of a police investigation that not only reveals why she was murdered, but also uncovers some other terrible murders that took place in the past, in Sausage Hall itself. The Sandringham Mystery is published by Bloodhound Books today. I hope you will enjoy it.

An author to assuage hunger…

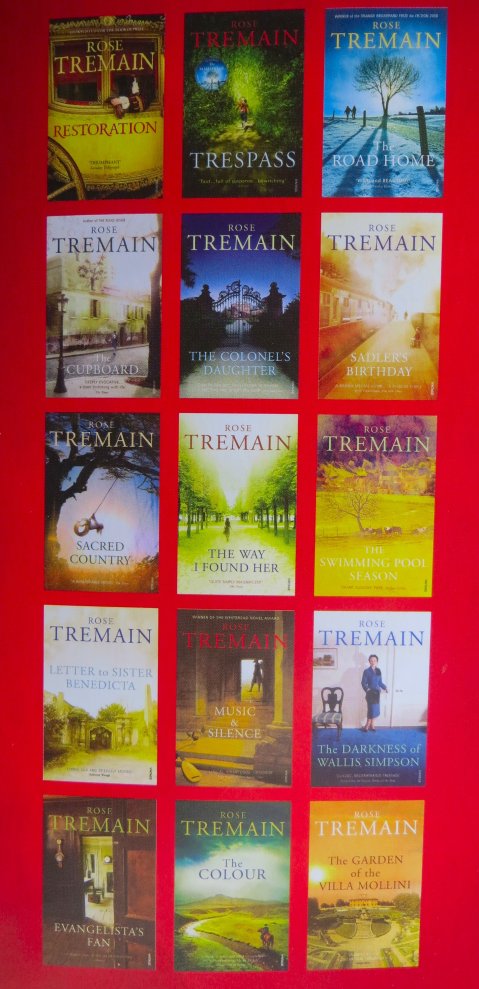

Discovering Rose Tremain

I remember exactly when I first discovered Rose Tremain. I had very recently joined Dillons (destined to merge with Waterstones within a year, though none of us knew that then) and had been invited to attend a party at Hatchard’s (a fine old bookselling business that had been acquired by Dillons some years previously) to celebrate its 200th birthday. Along with many colleagues, I accepted. As Dillons HQ was in Solihull, Teresa, one of our administrative assistants, was asked to find hotel accommodation in London overnight for those of us who requested it. Teresa had been supplied with a directory of hotels ‘approved’ by the company for use by its staff and, as I was to discover, had an unerring knack for picking out those that were most dismal and unwelcoming. Most of my colleagues made alternative arrangements. New to the company, I put my trust in Teresa’s mercy.

The party was the most glittering book trade bash I’ve ever attended. Princess Margaret was there, resplendent in elbow-length gloves and drinking something from a tall glass wrapped around with a linen napkin. Salman Rushdie had dared to attend, even though it was only a year or so after the fatwa against him had been issued. The other guests included dozens of well-known writers and publishers. As you can imagine, security was very tight.

The evening was ‘elegant’. I use the term in a way that was new to me then, but in which I’ve had other occasion to use it since. As I’ve previously mentioned, the first bookselling company that I worked for was in Yorkshire and the second in Scotland. Both hosted many literary events and all of these shared a single prominent common feature: we ensured that our guests were served a plentiful repast of excellent food. We believed in feeding the body just as much as the mind. In Yorkshire, we favoured sides of salmon, roast hams, salads, pizzas and quiches and generally included a selection of gooey puddings; in Scotland the food was usually hot and hearty: soups, pies, lasagnes, stews and curries. But always food, ‘proper’ food, and plenty of it. And drinks, too, of course, though the food was paramount.

At the party at Hatchard’s, on the other hand, the wine flowed but the food was sparse. Exquisite, but sparse. It consisted of tiny canapés that were delivered individually at long intervals by uniformed waiters and waitresses who bore them aloft on circular trays. There were miniature salmon rolls, morsels of pastry stuffed with even smaller slivers of meat and cheese, the babiest of baby sausages skewered with eighths of tomato and Lilliputian biscuits bearing deftly-placed dots of pâté, each one garnished with a parsley feather. The waiting staff weren’t particularly keen to distribute these fairy victuals, either: sometimes it was impossible to snatch one before it continued on its airborne journey through the crowd.

The upshot of this was that, when eventually I arrived by taxi at my hotel, which belatedly I had discovered was situated in the further reaches of Camden, at around 10 p.m., slightly tipsy and completely famished, I found that not only did the establishment serve no food (it would not even be providing breakfast on the following day), but that there was no restaurant or even a takeaway within a radius of at least a mile. I took one look at the dark and dingy street beyond its none-too-hospitable doors, and decided that I would be foolish to risk venturing forth in quest of sustenance now. I therefore toiled up the three flights of stairs to my room (it wasn’t the sort of hotel that offered to help with luggage) where I found a narrow single bed in a cheerless room with no bedside lamp and an ‘en suite’ shower behind a plastic curtain in an alcove. The lavatory was outside, shared with the occupants of the other rooms on the same floor.

Mercifully, my room did contain a kettle and some sachets of coffee and tea (the brand-names of both were unfamiliar) and two or three of those little bucket-shaped plastic containers of UHT milk. Too cold and hungry to go straight to bed, I made myself a cup of indifferent but scalding coffee, groped in my bag in the hope that I hadn’t absent-mindedly eaten the cereal bar that I’d placed there some weeks before (I hadn’t) and fished in it again for the book that I’d snatched from a stash at Dillons HQ for staff to help themselves to before I’d caught the train to London many hours earlier. It was Restoration, by Rose Tremain. Immediately, I was enthralled. I drank my coffee, ate my cereal bar and read. And read. I went to bed some hours later, my hunger forgotten, and slept soundly until the following morning, when I rose early in order to find breakfast and get another quick fix of Restoration before the day’s work started. I had become a Rose Tremain addict.

I had intended this post to be a review of Merivel: a man of his time, by Rose Tremain, which I have just completed, but I’ve probably written as much as you want to read for now, so will save that for another day.