The most atmospheric of writers…

One of the great pleasures to be obtained from reading crime fiction is that most crime writers are acutely aware of both the geography and the mood of the communities that they write about. I won’t claim that there is such a thing as national character – I know that I shall immediately be shot down in flames if I even hint at it – but I’m certain that the massive popularity that Scandinavian crime writers have achieved owes a significant debt to the ambience of their work: the dark nights and cold days that they evoke, which in turn inspire brooding and melancholy characters who seem determined always to spot the worm in the bud, despite the consummate beauty of their surroundings. Similarly, the novels of Donna Leon and Michael Dibdin, which are set in Italy, skilfully succeed in communicating the rich cultural heritage of that country.

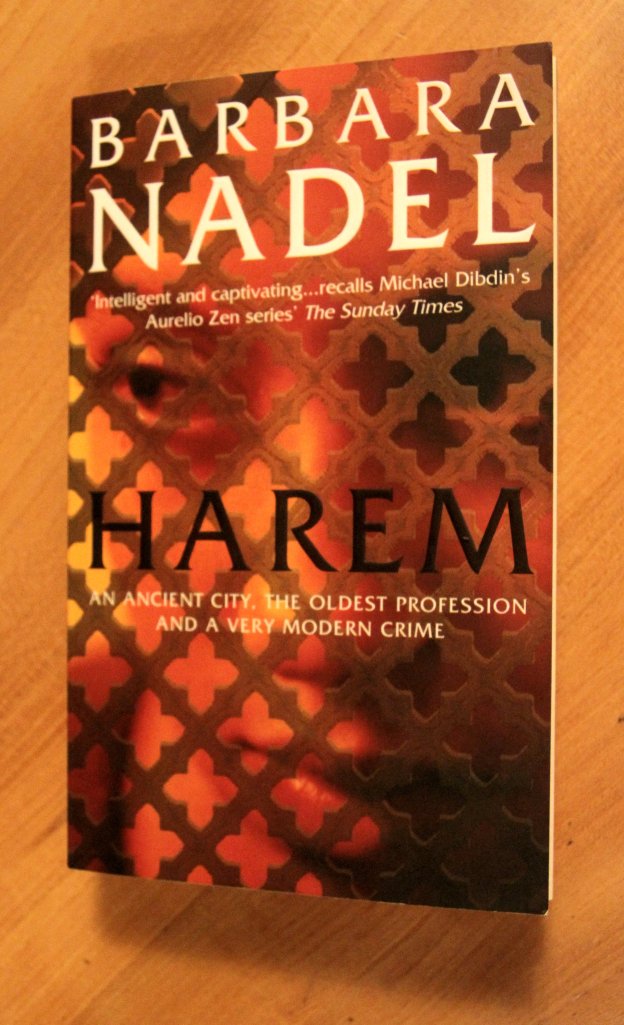

No-one, however, captures the essence or psyche of a country better than Barbara Nadel. Perhaps I should say city, rather than country, as all of her novels that I’ve read have been set in Istanbul. With apparent ease, she captures the contradictions of a city that has always looked both East and West: its exoticism and squalor; the brutality of some of its people and the sophisticated philosophical outlook of others; the thrusting modernity that jostles but does not oust more ancient superstitions. Other writers have written eloquently about this city, especially Orhan Pamuk, whose Nobel prize-winning work, so exquisitely wrought, seems to derive its depth from these very contradictions; yet, in my opinion, no-one, not even Pamuk, surpasses Nadel’s descriptions of Istanbul’s mean streets and boisterous crowds when she is writing at her best.

I’ve read three or four of her books now. I particularly admire her depiction of her world-weary but wise and humorous detective, Çetin Ikmen, who is beleaguered not only by the absurdities of red tape and the inefficiency and bigotry of his colleagues at work, but also by his large, unruly and ever-growing extended family at home. The latter is presided over by his ebullient and chaotic, much less well-educated wife, Fatma.

Harem is a particularly accomplished novel, because it examines issues of profound significance in Western countries through the filter of setting them in Istanbul. This not only makes it easier for the Western European reader to read about them, but also points up the dual thinking still prevalent in almost all countries by presenting it as a peculiarly Turkish phenomenon. This provokes the immediate response: ‘That couldn’t happen here!’, followed soon afterwards by: ‘Or could it?’ The original crimes committed in Harem are rape and the exploitation of women, leading in some instances to murder. The first of the murder victims is Hatice, a friend of Ikmen’s teenage daughter Hulya. Nadel’s account of Ikmen’s boss’s reluctance to pursue the girl’s murderers and bring them to justice because she evidently was not a virgin before they attacked her is particularly poignant. We might try to flatter ourselves that such an attitude could not prevail in our country, were it not that only in the last few days a British barrister has described a thirteen-year-old girl against whom sexual offences were committed as ‘predatory’. Nor does Nadel pull her punches when it comes to describing the perpetrators of rape. Hatice had unwittingly become involved with a group of people practising organised depravity, but her case is mirrored by one even closer to home for Ikmen, that of the abusive relationship that exists between two of his own police officers. As one would expect from a writer of Nadel’s talent, the moral conclusions that she draws are complex, but she is quite clear that women should never suffer from sexual abuse, whatever their personal moral code. This message may seem obvious, yet it is one that societies everywhere seem to be taking a long time to digest. Harem makes a very valuable contribution to the debate.

Of the other characters, several old friends feature in this novel. My particular favourite is Mehmet Suleyman, Ikmen’s disdainfully aristocratic colleague, who in this book finds himself less able than usual to sail, cosseted and immaculate, through his life, as if the teeming, grubby throng of humanity that it is his job to police does not really exist. Suleyman’s volatile Irish wife is suffering from post-natal depression and he has to run the gauntlet of her tantrums and her misery. And then there is Fatma, impossible but lovable, weaving her idiosyncratic magic on her weary but essentially adoring husband.

I wholeheartedly recommend Harem. If you’re new to Barbara Nadel, you won’t lose anything by starting with this book, as, despite being one of a series, it stands completely on its own, as such novels should. However, I’m certain that, if you do read Harem first, it will make you also want to sample some of the others.

German craftwork at its best…

When I wrote about the potter of Nottuln a few days ago, I said that I would also shortly be describing the sandstone museum at Havixbeck, near the German city of Münster. It is a fascinating modern complex, aimed at tourists, though there is no charge for it and it is not situated in an area particularly noted for tourism. It is a place designed to celebrate and record an ancient craft: part museum, part atelier. Some of the exhibits have been displayed in reconstructed rooms as they might have existed in the past.

The museum celebrates more than five hundred years of sandstone carving (illustrated in the photographs here) by the three linked communities of Havixbeck, Billerbeck and Nottuln. Men from these communities worked together from the late middle ages onwards, forming themselves into a kind of guild. They did not regard themselves as artists, rather as craftsmen, and therefore most of the pieces that they made were created anonymously. It wasn’t until the nineteenth century that a few individuals began to be named on the pieces, and these with no especial reverence. Until 1950, the workshops were often situated in the quarries where the sandstone was hewn.

The industry enjoyed a brief late flowering in the middle of the last century, when the sandstone workers were commissioned to undertake post-war repair work to the churches of the Münsterland. Thereafter, the industry went into decline (possibly linked to the simultaneously declining influence of the Catholic church in the area), though there are still a few artisans practising today. Many of the examples of the mediaeval sand carvings held by the museum were salvaged from bomb-damaged churches. There is an especially poignant photograph of Münster Cathedral, taken after a bombing raid, in which one of the twin towers has almost collapsed; the other is miraculously unscathed. This church has now been beautifully restored.

The men who worked the sandstone doubled up as farmers when their masonry skills were not needed. For this reason, members from the three communities were quite wealthy. Perhaps it was partly because they also worked the land that they lived to be a much higher than average age for stoneworkers. In the nineteenth century the average life expectancy for a man from these villages was sixty-one, as opposed to a (shocking!) thirty-seven for stoneworkers elsewhere in Germany at the time. Modern science suggests that another reason was that, uniquely, the sandstone from this area contains lime, which cut down the dust emitted when it was being cut and carved, meaning that the workers inhaled less into their lungs. The workers themselves attributed their longevity to schnapps, of which each would drink up to a litre a day! (Apparently it was less potent then than it is now.)

The elaborate patterns for the windows, tombs, shrines and altars that the masons carved were designed by an architect, or sometimes by a master mason. In mediaeval times, the templates of the patterns were made of wood; later, of thin metal. The workers had a dour but well-developed sense of humour: quarrying the stone required a huge expenditure of skill and energy, so if anyone spoilt a piece of it by making a mistake they were fined. Even more humiliatingly, the piece of damaged stone was given a mock-ceremonial burial. Money collected from the fines contributed to a kind of early benevolent fund. There are indications that the masons were quite hard-nosed businessmen: for example, almost every farm in the area has its own sandstone shrine – no doubt the eighteenth or nineteenth century equivalent of a nice water feature (if that doesn’t sound too profane).

Dating from the nineteenth century onwards are photographs of the boys and men who worked the quarries. They don’t have happy faces: all seem quite solemn and few are smiling, but perhaps this was because it took such a long time to take a group photograph then, perhaps because they were told to look serious. They certainly appear well-dressed and well-fed, though it is curious that their clothes hardly seemed to change in the century between 1850 and 1950.

I wonder what it must have been like to have been born into one of these three villages and – male or female – to know that during your life you would be assured of reasonable prosperity, but also that your future had been mapped out for you from birth.

Profile of an artisan potter

I have recently visited Münsterland, the area around the city of Münster in Germany, and, in particular, a triangle of prosperous villages, Havixbeck, Billerbeck and Nottuln, all associated since mediaeval times with sandstone carving, and the latter with a characteristic blue-glazed pottery. Being lovers of individual, hand-crafted products and of clayware, my husband and I tried in vain by car to find a contemporary artisan in the district, as we had seen examples locally; yet it wasn’t until, on a bike ride towards the end of our stay, we happened upon a glass display case fixed to the wall of a Nottuln hotel that we could locate the potter. The case contained some examples of the work, some photographs and, tucked away at the top, some cards with a name and an address, out in a rural hamlet called Stevern.

Good luck happened twice, as, when we found the pottery itself, Monica Stüttgen had only two hours before returned from a holiday in the Black Forest. She showed us into her house and invited us also to look around the garden, both of which are a treasure trove of beautiful examples of her handiwork. The whole of the ground floor of the house is given over to a studio and rooms displaying a remarkable range of artefacts, quite a few of them carrying her trademark, a flying bird with a fanning tail.

Monica says that she regards herself as a craftswoman, rather than an artist (coincidentally, this is also how the many generations of sandstone sculptors also viewed themselves) and feels particularly strongly that her pottery should be used, not just put on display; it is well glazed, using modern processes, and, she adds, will stand both frost and the dishwasher! Though it accords with traditional designs, it plainly reveals much of her individuality and considerable artistry.

I’ve included in this post some photographs of some of her work, from both inside the studio and out in the garden. She obviously draws some of her inspiration from Nottuln, of which she is a native, although she told me that she spent ten years making and selling pottery in France. Like many artisans – indeed many writers – that I have met, her chief problem is obtaining publicity for her work. Once people have seen it, they love it and want to come back for more, but she is struggling to find a wider public; at the moment, she does have an arrangement with the local restaurant, Gasthaus Stevertal, to display examples of her pottery (Stevertal is a fine traditional German restaurant with a menu that features the local cuisine – we ate here twice… and twice missed her display!) and the showcase in Nottuln, but these are not enough.

I found both Monica and her work fascinating and I am full of admiration for what she is trying to achieve. I suggested that she should try to extend her customer base by developing a blog for her website and new contacts via social networking; I also promised to write a blog-post myself as my own, very small, contribution to try to help. So here it is.

We bought a fruit bowl, a fish plate and two eggcups and Monica very generously also gave us a kitchen tidy in one of the traditional Nottuln designs. I’m delighted with them and doubt that I shall be taking any risk on the dishwasher front! As our daughter-in-law also comes from this area, we shall certainly visit the pottery again: there are many other pieces that we should like to buy. For example, we were particularly taken with the ceramic garden labels for herbs.

I feel very strongly that the skills of an artisan should be encouraged and supported, especially one with Monica’s obvious talent. If you happen to visit this area, you won’t be disappointed by an hour or two in her lovely studio and garden. You may like to know that she is also prepared to send items by post!

Led to a lovely real place by reading a magical book…

[Click on pictures to enlarge them.]

Though I’m not a travel writer, I’d like to share a recent visit to a place I had previously never considered exploring, but, having read a book by a Facebook and Twitter friend and seen pictures of it on her pages, I resolved to stop and have a look at her world. I occasionally pass close to this location, but am always en route to somewhere else (Aren’t we all?), with deadlines and people to meet, and it had never before spoken to me with seductive siren tones nor even given me a glimpse of its hidden beauties and charms.

This time, I wasn’t even sure if we would manage the detour, but my husband and I started out early from Germany and covered the intervening kilometres without delay, aided by what he had always previously eschewed but which now proved absolutely essential, sat nav. Negotiating foreign cities, especially those with road systems apparently designed to doom motorists to madness, is always fraught with tension; navigating Rotterdam’s streets may be a piece of coffee and walnut to its residents, but without help or prior knowledge, the new visitor might as well be in the wilderness.

We were heading for Oude Haven, the ‘Old Port’, or the oldest harbour in the city, now home to a collection of historic Dutch barges which Valerie Poore, @vallypee, not only writes about in her books, but has lived on and restored here, for Oude Haven is a working museum with a team of enthusiastic owners, metal- and wood-working skills and the heavy gear to lift huge vessels out of the water to repair and return them to their original state.

I can tell a nightmare story of parking in Amsterdam, which perhaps I’ll relate here some other time, so we were prepared with plenty of small change to feed the greedy meters and defy the wardens, when we eventually turned into Haringvliet, which we had strolled down on Google Maps and determined as our best stopover point for the harbour; however, our research had not been thorough enough, as we discovered that the meters are not fed with money, but with prepaid cards to be got from a range of locations (however, it was a Sunday and we had no means of finding them easily). Then we discovered, by dint of guessing at the truly double Dutch meter instructions that some meters could be accessed by credit card, but we couldn’t immediately see one of those. The masts of the barges and the gorgeous array of moored boats just in front of us seemed to float off into the mists of meter mania.

Rescue came in the form of a bluff but very personable gentleman who had just been buying flowers from the stall at one end of Haringvliet, where, he said, was a credit card meter. Not only did he walk us to it, but used his own card to meet our two-hour stay and accepted our cash payment only very reluctantly. How’s that for hospitality?

The way was now open to explore, albeit quite briefly, the harbour and to locate Vereeniging, the elegant barge belonging to Valerie. The place is a marvel of architecture, considering that most of the area was flattened in WWII. Perhaps most striking is Het Witte Huis, The White House, an art-nouveau skyscraper building designed by architect Willem Molenbroek and erected in 1897-1898, which miraculously escaped destruction in 1940 and which still towers over the port, though it has long since lost its original place as the tallest multi-storey structure; the eye is then ineluctably drawn to the astonishing ‘Kubuswoningen’ or ‘Cube Houses’, the 1984 brainchild of architect Piet Blom, just along the wharf.

But we were here, as lovers of English canal boats and boating, to look at what was on the water (or, in the case of barge Luna, raised out of it to the dockside repair cradle and undergoing some heavy metal treatment – welding was well under way, if the boat wasn’t!). The barges are remarkable, with their sheer size, huge masts and characteristic leeboards (for they are sailing cargo vessels), and we should have loved to have been able to look inside them.

Vereeniging, just about the smallest of them all, nestled in her elegant green and red livery amongst the others… and I could see at a glance what had captured Valerie’s heart about her. She seemed so much more of a living presence, thanks to my reading of ‘Watery Ways’, and her character was buoyant and bubbly, with all the sprightliness and effervescence of a gig compared to the barouche landau sedateness of most of the other boats. I can’t wait to read the next instalment of her history, ‘Harbour Ways’, now in the making! An old bicycle stood to attention on the deck; theft of about eight others has made the owner chary of leaving a valuable machine on board.

We walked around the harbour, ate and drank local beer at one of the cafés (probably not the best one!) and captured a picture of Vereeniging’s stern from across the water. Strolling back along the other side of Haringvliet, we came upon the corpse of a once-yellow bicycle rescued from the muddy depths (but unlikely to be restored like the barges!) and said hello to a ship’s cat, a ginger pirate with the capacity to leap eight feet from deck to harbour steps and to take his ease in the sun.

But time had sadly run out for further sightseeing. We had avoided the parking police, thank goodness, and sailed away to Europoort with the powerful sensation of having travelled to somewhere very special indeed. The homeward ferry was a terribly disappointing contrast to what we had just been seeing.

The idyll and the agony, with Anne Zouroudi (@annezouroudi) …

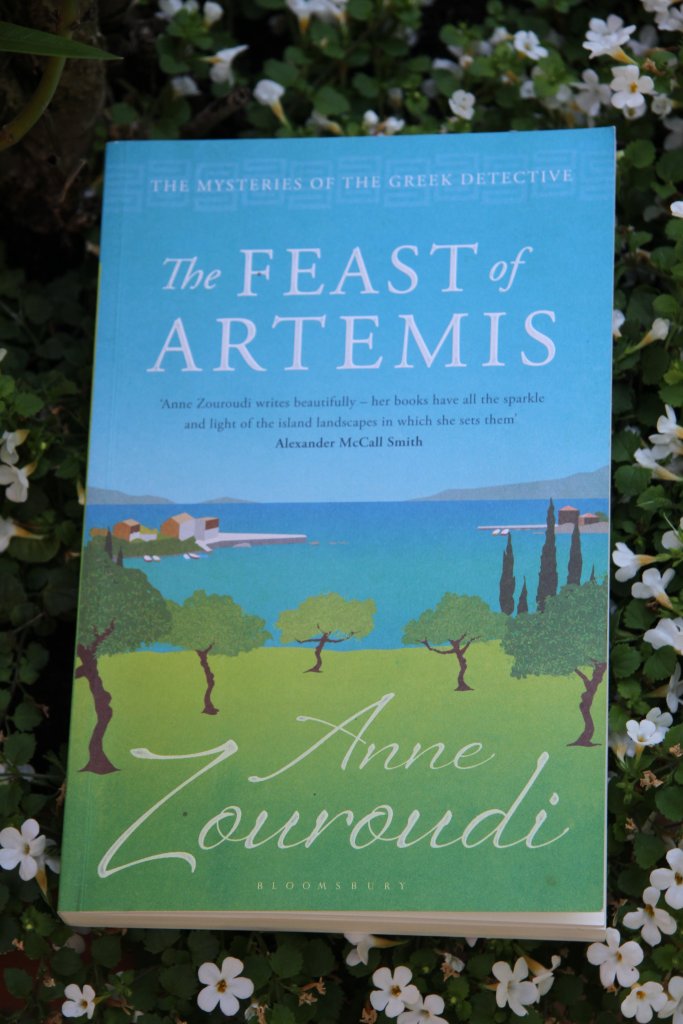

The Feast of Artemis is the seventh novel that Anne Zouroudi has written about her mysterious amateur detective Hermes Diaktoros. It’s only the second of the series that I’ve read – I completed The Messenger of Athens last year, shortly after hearing Zouroudi speak at a crime writers’ evening held at the offices of Bloomsbury, her publisher – so I now have the very great pleasure of being able to look forward to devouring the other five. I shall buy them as soon as I can.

I find the quality of Zouroudi’s writing almost haunting. It is classic in that it belongs to the oldest European literary tradition of all, that which has Homer himself sitting at its head. I’ve written elsewhere about how Zouroudi’s intensely poetical yet austerely precise descriptions of the Greek landscape remind me of Homer’s own accounts of the Greek islands in The Odyssey, which, more than two millennia after they were conceived, still amaze with their freshness. The Feast of Artemis also contains such evocative passages, but Zouroudi – always reinventing herself within the universe that she has created – in this novel focuses especially on describing food. The clue, though, is in the title: as the reader is aware, Artemis is the feisty goddess of hunting; in Greek mythology, she at various times exacts retribution, and in the novel terrible things are done in her name, some with unforeseen and unintended consequences.

Just as beneath this glittering, sun-drenched paradise lives the peasant community of Dendra, whose members are tarnished with all the human vices, so concealed within their sumptuous festive meals lurk danger and destruction. Food is both the bringer of life and the harbinger of death in this novel. The finely-drawn characters, whilst naturally displaying none of the urbanity of Diaktoros himself, show both cunning and a taste for revenge that matches that of the gods of old.

The central plot concerns a generations-long feud between two olive-growing families. A cycle of vengeance and retaliation results in the death of the patriarch of one of these families and the mutilation by fire of a youth from the other. One of the book’s many masterly touches consists of a kind of tightening of the screw as the plot unfolds: we are told early on that the youth has been burnt, but the full significance of this is not revealed until the closing stages. The small clouds that hover over the sunny landscape right from the beginning grow darker as the novel progresses and the effects of evil are revealed.

Yet such is the author’s subtlety that none of the characters in The Feast of Artemis is evil through and through. The publisher has placed it within the crime genre, probably correctly, but it belongs to that relatively small group of distinguished crime novels that can be read on more than one level. Fundamentally, it is a book about the human condition. Although Hermes was the messenger of the gods, and Hermes Diaktoros, in his guise as moral arbiter, shares some of his namesake’s characteristics, he is also a modern-day Zeus, swooping down, not in anger, but with a kind of sadly humorous wisdom, as he conducts his inexorable quest to get at the truth and show the perpetrators of the crimes the errors of their ways. That he himself has foibles is a stroke of genius: in a place where life and death are governed by food, he is continually tempted by delicacies that threaten his own well-being because he is already overweight. It also emerges that he is brave to eat some of the food that he is offered, knowing as he already does that those providing it are guilty of introducing poison to their seemingly delicious comestibles. Yet he is nimble on his tennis-shoe-clad feet and has a brain of quicksilver. That he is not perfect lends authority to his perspicacity and ensures that it is not marred by overt moralising. Another fine touch is the introduction of his brother Dino, who is as much a slave to wine as Hermes is to food: Dino – the echo of the name is surely intentional – plays Dionysius to his Zeus. (I’m not sure whether Dino also appears in some of the five novels that I haven’t yet read: my guess is that this is not his first appearance in Zouroudi’s oeuvre.)

At the end of the book, resolution is achieved, but at a price. Peace is brought to the community of Dendra, but it is made clear that its inhabitants will continue to bear the scars – and in some cases, to pay custodial penalties – for their wrongdoing. Hermes Diaktoros himself, having arranged to pay for the best plastic surgery that money can buy for the damaged youth from his own seemingly bottomless yet inexplicably acquired funds, simply melts away. God’s in his heaven, all’s right with the world – until, we hope, the next time that his intervention is required.

If you haven’t yet read Anne Zouroudi, you should; you will find her compelling command of the Greek ‘idyll’ as stuffed with flavour and irony as the roasted lamb from the fire pits of her opening chapters in this book.

A fair bit of nostalgia…

As a child I always visited the circuses and funfairs that came to Spalding, because my great-uncle, who kept a shop, was given free tickets or tokens for rides in return for placing advertising posters in the shop windows. I was never very keen on circuses – the captured animals forced to perform tricks, their eyes sad and defeated, troubled me even then. But I loved the funfairs! Yesterday, I stumbled upon one completely unexpectedly when stopping to walk in a small picturesque village when out for a drive.

I hadn’t been to a funfair for many years. The last time that I can recall was during a holiday in France, when my family and I were passing through the handsome old Roman town of Saintes and saw that it was en fête. The main street of the town, which is shady because of the plane trees lining it on either side, had been cordoned off and a modern funfair set up adjacent to the ancient manège (roundabout) that always seems to be there when we visit. I remember that fair especially for its mingled scents of hot metal, warm sugar and cooking meats.

Yesterday’s fair presented me with a similar surge of aromas. The heated metal and candyfloss smells were particularly pervasive in the warm sunshine. What also fascinated was the very dated appearance of the rides – dodgems, cakewalks, giant rocking-boats, one of those terrifying cylindrical rides that depends on centrifugal force not to tip its occupants onto the tarmac as it bends and tilts and, for the younger children, bobbing yellow plastic ducks to ‘catch’ with magnetised canes as they swim endlessly round tiny artificial rivers and a small roundabout of aeroplanes fitted with joysticks for their infant pilots to manipulate them up and down – all standard fairground machinery, perhaps, but, extraordinarily, existing as if in a 1950s time-warp. Each piece was painted and decorated in the same way as those of the fairs that I remember in Spalding as a very small child: there were pictures of Marilyn Monroe and Laurel and Hardy; the cylindrical ride was even topped with a figurine of Elvis Presley.

What transported me back into the past yet more vividly was the wonderful carnival atmosphere that the fair brought with it. Whole families had gathered and were chatting, happy and relaxed, in the streets. Children danced giddily off the rides and played next to them with their friends or tugged at their parents for the cash to buy another go. Fathers pushed buggies and women congregated in groups, sipping coffee or nibbling ice-creams. A local café was selling half-pizzas. Hot dogs, hamburgers, candyfloss and giant sweets proclaiming ‘I love you’ together gave off their distinctive mingled scents. There wasn’t a mobile phone or an iPad in sight. For a couple of hours, it seemed as if I had stepped through the looking-glass into an era of lost innocence and almost forgotten leisure, when it was OK to while away the afternoon doing not much in the company of others doing the same.

Of course, being a crime novelist with more than my fair (!) share of cynicism, I still had my eyes open to the possibility that the opportunity for some nefarious deed might be lurking below the holiday surface. The killing of a young girl on a fairground ride featured in a televised crime programme not so long ago; though she apparently just fell from the ride, she had in fact been stabbed. My eyes turned to the giant fan-belts that powered the more terrifying of the machines; they, too, belonged to a bygone age, an age that depended on a mechanical rather than an electronic infrastructure. What if they had not been inspected with sufficient rigour when the fair was erected? What if a madman were to interfere with them and bring horror to the happy scene? Please don’t worry about me; it’s all just a bit of internal fiction… and I did have a wonderfully nostalgic time!

A merciless killer…

A half-tunnel of hedgerow shades the path from the sun; new bramble tentacles rear up and across the way, reaching for light, their tips still soft, but their stems already clutching at clothing; rabbits are nervous tics at the edge of vision, ready to bolt. This is a lonely, little-used link between roads, though at one end, in the undergrowth under the hazels, illicit, smutty relationships are consummated and discarded with their condoms; the entrance by the field gate, where cars can pull in, is a drift of fast food bags, cartons and fly-tipped debris. Ah, the beauty of rural England!

It is, in fact, part of a favourite walk for us and, especially, the dog, since pheasant and partridge are here in numbers; he will hold a point for over half an hour, which would, were we shooters, make a twelve bore superfluous – a butterfly net would make better sport. As I climb over the stile into the field, where a small herd of bonny brown cows and calves grazes the bank, I encounter a neat heap of dark feathers. The Python team would call this a late blackbird, too late in its take-off to escape the trademark kill of the sparrowhawk. Foxes and cats dispatch their prey untidily, scattering feathers far and wide and often leaving other debris as well. The sparrowhawk, by contrast, is the most thrifty and purposeful of murderers. He calculates. He acts with intent, each action precise and pre-meditated. He uses the terrain, hedges being particularly appropriate for his silent up-and-over surprise attack. Small birds may just flit into the dense hedgerow in time, but his yellow-rimmed eyes are burning with bloodlust and his whole being utters supremacy. He extracts nourishment gram by methodical gram from his hapless quarry, gorging on blood, flesh and bone until there is nothing left except that pathetic heap of feathers, dropped straight down from the branch on which he sits as he feasts.

Imagine that you are the sparrow or the blackbird, caught in those dread talons even as you realise the danger, so swift is the arrowed form. At least your exit is quick.

My new acquaintance…

In yesterday’s post, I wrote about my visits to Burlington House and said that I’d met an interesting new acquaintance. Her name is Andrea and she has recently been appointed to the newly-created position at the Royal Society of Chemistry of Diversity Manager. (Her work will be vital in not only attracting minorities of all kinds to the study of chemistry, but also in helping to develop their careers later on.) Prior to that, she was a forensic scientist for thirteen years, until the government closed down its forensic science unit.

My ears pricked up when I heard this. I was also fascinated to learn that Andrea was brought up in a village close to mine. More than once I’ve made DI Tim Yates say that he doesn’t believe in coincidences, but truth is obviously stranger than fiction, as this is the second big coincidence that’s happened to me in less than a week (the first was meeting Carol Shennan, with whom I was at school in Spalding decades ago, in Bookmark).

Andrea has kindly agreed to be interviewed for the blog in a few weeks’ time. She’s also sent me an article that she wrote about being a forensic scientist for Chemistry, the RSC’s magazine. I won’t spoil my future post after I’ve interviewed her by quoting too much from it now, but here is a taster:

I became a forensic scientist long before shows like CSI and its spin-offs resulted in the general public having a distorted view of how forensic science is used by police forces to investigate crime. Forget Armani suits; most of the time we were dealing with skanky knickers, jumpers crawling with bugs, and clothes so sodden with blood that they had gone mouldy in the packaging.

A DNA profile in minutes – no chance! Our quickest test took around 12 hours and there were times that we had to wait well over a week. CSI also doesn’t show the endless samples of ‘touch DNA’ that fail to give a DNA profile at all, or ones that give a profile so complex it is uninterpretable. Nor do they feature the heart-wrenching cases that demonstrate the depravity that exists in our society: cases involving babies, the elderly or vulnerable; people who are murdered simply because they were in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Riveting, isn’t it? I look forward very much to talking to Andrea again soon.

I happen upon a murder… in a very grand place…

Over the past week I’ve spent three days (day job) at the Royal Society of Chemistry’s HQ, Burlington House, in Piccadilly. The building is also the home of the Royal Academy of Arts, the Society of Antiquaries, the Linnean Society, the Geological Society and the Royal Astronomical Society. It is an amazing place: turning your back on the dust and roaring traffic of Piccadilly, you enter an archway and are immediately transported into an enchanted world that carries with it all the grace and serenity of the finest seventeenth-century architecture – a mini-Versailles in the heart of London.

Intrigued by its splendour, when I was there yesterday I asked if there were any record of its history. I was given several pamphlets and leaflets and discovered on the first page of one of them, The Story of Burlington House, by Dennis Arnold, that in earlier days it was the scene of what was almost certainly a domestic murder.

The original Burlington House was built by Sir John Denham, a wealthy lawyer and poet (he was also Surveyor General to the Crown) for his new bride, Margaret Brooke. She was eighteen and he was fifty (and apparently limped). Margaret very quickly became the mistress of James, Duke of York, who had attended their wedding (and was later to become King James II). Their affair was common knowledge, as certain salacious entries in Pepys’ diaries make clear.

Margaret was found dead at Burlington House, evidently from some kind of overdose. Everyone assumed that Sir John was responsible for her death, though he wasn’t brought to trial. Despite her infidelity, public feeling ran high and Sir John’s life was threatened by the mob if he tried to leave the building. He managed to achieve the complete about-turn of the populace’s emotion by providing Margaret with a magnificent funeral, with ‘four times as much burnt wine as had been drunk at any funeral in England.’

Sir John did not stay long at the house after his wife’s death, however. Perhaps he could not bear this constant reminder of the collapse of the domestic idyll that he had planned; perhaps he was haunted by guilt every time he saw the place where she died. In 1668, Burlington House was bought by the first Earl and Countess of Burlington, who gave it its name.

I’ve never considered writing historical fiction, even if it’s about crime, but this story has captured my imagination. Perhaps I’m destined to write about Lady Denham, who I’m sure would have had a great deal to say in her own defence – married as she was to a (probably nasty) old man and (probably) unable to refuse the overtures of a future king.

I’ll write some more about Burlington House in a future post. I’ve not yet even started to describe its wonderful literary legacy, or the fascinating new acquaintance whom I met there yesterday.

Happy coincidences and old friends at Bookmark, Spalding…

Yesterday was one of those perfect days that become legendary in memory. I had travelled to Spalding, having been invited to give a signing session at Bookmark, a very distinguished bookshop which I also visited and wrote about just before Christmas last year.

There was a carnival atmosphere in the town. Christine Hanson, Bookmark’s owner, was feeling particularly happy, because hers and other businesses in Spalding had banded together to offer fun activities to passers-by in one of the yards in the Hole-in-the-Wall passageway. Christine said that it marked a significant step forward in the town’s initiative not only to save the high street but also to ensure that it thrives. She flitted back and forth between the shop and the Hole-in-the-Wall all afternoon and, despite being so busy, still provided my husband and me with her customary wonderful hospitality.

My signing session began with a remarkable and totally unexpected coincidence. Two ladies who had been paying for books at the till came over to speak to me. Noticing their accents, I asked if they were American. One of them said that she’d been born in Spalding, but had lived in America for twenty-five years. She now teaches environmental science at the University of California. Judging her to be about my age, I asked if I knew her. She said that her name was Carol Shennan. I knew the name immediately; she had lived about five doors away from me in Chestnut Avenue when we were both growing up. She said that her mother, who is eighty-nine, still lives in Spalding, and that she was just there for the week to visit her. It was an unbelievable stroke of luck that we should meet in Bookmark. Carol bought In the Family, and I look forward very much to receiving a future contribution to this blog from her when she’s read it.

Several babies came into the shop. I was introduced to Oliver, who arrived with his grandmother and aunt, who each kindly bought both books, and Harry, who came with his grandparents. His grandfather (I’m sorry that I can’t remember his name: his wife’s name is Carole) is a keen local historian and said that he doubted that my novels would cover villages as remote as Sutterton, which is where he was born and still lives. By another strange quirk of coincidence, I was able to tell him that my third novel, which I’ve just started writing, is set in Sutterton. I hope that Harry’s grandparents also will contribute to the blog when they’ve read the copy of In the Family that they bought.

My very dear old friend Mandy came in and bought an armful of books to give other friends as presents, just as she did at Christmas. At the end of the afternoon, she returned to guide us to her house, where we spent an idyllic evening eating supper and drinking wine in her garden with her husband Marc and her friends Anthony and Marcus. We ate new potatoes, broad beans and strawberries from her allotment and talked about books, teaching and cooking (Marcus is a chef). Afterwards, we drove home through the twilight. The fields of South Lincolnshire were looking at their best: the corn was just turning, and in one place acres of linseed coloured the landscape blue-mauve. The skies were as big and beautiful as always.

An idyllic day, as I said. I’d especially like to thank Sam at Bookmark for arranging the signing session, and Christine, Sally and Shelby for looking after me so well and for providing a great welcome: I heartily recommend the café at Bookmark, if you’re ever in the area. Many thanks also to the many people who stopped to speak to me – the conversations were fascinating – and for buying the books. And thank you, Mandy and Marc, for being amazing hosts and for introducing us to Anthony and Marcus, who provided me with their suggestion for DI Yates 4!