Think of a number…

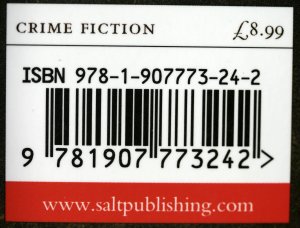

When I got my first job in the book industry, the ISBN was waiting in the wings. It was actually doing a little more than that – people in the trade were encouraged to quote the ISBN on orders, and printed order forms usually included them. By the end of the 1970s, almost all books had an ISBN printed on the back cover. Yet, while these rune-like digits were not exactly a sham, they served no useful purpose either. I remember my first boss asking me what I thought of ISBNs. I shrugged. They meant little more to me then than the ‘By appointment to the Queen’ notice on a marmalade jar. ISBNs – the brainchild of a HarperCollins director called Carl Lawrence, one of the grand old men of publishing in my youth – were like the dummy burglar alarms that some people attach to the front of their houses: they indicated, even warned, of something that was not actually in place. That something was a well-organised, automated book industry supply chain.

The trade was quick to catch on, though. By the end of the 1970s, teleordering had been invented and the bigger bookshops and bookselling chains were experimenting with EPOS systems. Some publishers’ reps had handheld devices by which they could transmit orders to head office as they received them (these very early forerunners of the iPad bore about as much resemblance to it as Dom Joly’s giant spoof mobile bears to Apple’s sleek invention today). For the first time, booksellers and librarians were able to identify the correct edition of a book by inspecting the magic barcode on the back. All of these breakthroughs depended on the humble ISBN.

There were some hiccoughs, of course. Rows about how ISBNs should be used erupted right from the start. Eventually it was agreed that not only every edition but also every format of a title should have a unique ISBN. This was a relatively simple concept in an era when most titles appeared first as hardbacks and then as paperbacks if they were successful. Some publishers, however, persisted in allocating ISBNs to non-book material – to posters, for example, or to book packages. I remember arriving at work one day to discover forty dumpbins of a James Herriot title dumped – literally – on the doorstep. I had ordered forty copies, but the publisher had allocated the ISBN to the dumpbin, not the book.

Nevertheless, the ISBN was a wonderful invention. For the first time in its history, the book industry basked in praise for being so innovative. We were told that our use of the ISBN was rivalled only by the ingenious cataloguing mechanism developed at the same time by the car parts industry. This was praise indeed!

Today, ISBNs are ubiquitous. They are used by publishers in most developed countries and routinely quoted by customers when ordering books. (As a purist and something of a pedant, I shudder every time I hear someone say ‘ISBN number’. ISBN, of course, stands for International Standard Book Number, so the added word ‘number’ is redundant. Americans have got round this by creating a word from the acronym – they refer to ‘IZBENS’.)

And, amazingly, considering that all we are talking about is a set of digits, ISBNs still stir up controversy. Now that e-books are available in so many formats, publishers and booksellers are asking whether it is really feasible to allocate a unique ISBN to each. Bibliographic agencies, librarians and some booksellers and publishers say that it should be. Other booksellers and publishers disagree.

Elly Griffiths and Tom Benn in fine form at Breckland!

The small Norfolk town of Watton yesterday afternoon braced itself for bleak and squally weather, the rain coming in short eddies between gusts of wind that made the temperature seem even colder than it was. Inside, the library was a haven of warmth and hospitality, as Claire Sharland and her colleagues put the finishing touches to the Breckland Book Festival crime-writing event and offered welcoming cups of tea.

Elly Griffiths, Tom Benn and I all arrived early, as requested, and gathered in a small office to introduce ourselves and get to know each other a little better before we were ‘on’. I was fascinated to discover that Elly also writes novels about the Italian ex-pat community as Domenica de Rosa, her fabulous real name, and that Tom was encouraged to publish by his tutor at UEA, who helped him to place his first novel, The Doll Princess, with Jonathan Cape.

When we emerged from the small office at 3 p.m., the events space in the library had filled completely with people. I estimate that there were about forty in the audience – an impressive turn-out on such a dismal day.

Tom and Elly both read from their latest novels. Tom made the distinctive Mancunian dialect in which he writes come alive with his reading and, by doing so, also brought out the sophisticated humour which runs like a fine thread through the whole of Chamber Music. Elly also chose a humorous piece of dialogue from Dying Fall, and made the audience laugh with her vivacious rendering.

We were fortunate to have such a receptive and intelligent audience. Most had read the work of one of the authors; some had read both. Their comments and questions took in a discussion about the two writers’ very different but, in each case, key use of topography, character development, how each uses his or her writing to explore and develop relationships and the extent to which they feel defined by belonging to the crime writing genre (they don’t). We even managed to get on to some more general topics, such as e-books, authors’ royalties and the Net Book Agreement (the latter introduced, not by me, but by a member of the audience who had been a bookseller in the distinguished Waterstones bookshop at UEA).

Time flew in the company of Elly and Tom and their audience of like-minded lovers of literature. I had not read either Elly’s or Tom’s books before, but shall certainly keep them in my sights from now on. I hope also that we shall meet again in the future.

I can’t conclude without adding that the tea and home-made cakes with which we were rewarded at the start of the signing session were excellent. I’ve discovered that cake and conversation are two things that Norfolk does very well indeed!

Putting a person to a name… Waterstones Gower Street

As readers of this blog have often kindly expressed an interest in my books, I thought you might like to know that an event has generously been organised for me by Sam, the wonderful Events Manager at Waterstones Gower Street, on Thursday 21st March 2013. It will start at 6.30 p.m. and last for perhaps an hour. I shall be reading a short excerpt from In the Family and perhaps also one from Almost Love (which will be published in June), and offering a few tips, from a personal perspective, on how to get published. After this, there will be a short Q & A – and a glass of wine! The event is a sort of forerunner of a larger Salt crime event that will be hosted by Gower Street on 23rd May 2013.

I know that readers of the blog are scattered far and wide and that some of you don’t live in Europe. Wherever you are, I am very grateful to you for your interest and have been delighted to ‘meet’ you on these pages. For those of you who happen to be in London next Thursday or can travel there easily (and would like to, of course!), I should be delighted to have the opportunity to meet you in person.

Bring back the Net Book Agreement? I think so, yes…

I am quite often asked to explain why almost all bookshops display the same ‘Top 20’ blockbuster books so prominently in their windows and on front-of-store tables. Somewhat less politely, I’ve heard this referred to as the ‘W.H. Smith syndrome’. There are, of course, some magnificent exceptions, both in the independent sector and some of the chain bookshops, and I hasten to pay tribute to them. However, it is true that range bookselling is becoming rarer and more difficult to maintain in terrestrial bookshops, while, paradoxically, the so-called ‘long tail’ of publications from independent publishers and self-published authors becomes ever easier to access via the Internet. Both as a former bookseller who still believes in the power of being able to browse among shelves of print books and as an author who is published by a superb but still small independent publisher, this is a subject that concerns me greatly.

Incredible though it may seem to me, there is a generation of book buyers who have never paid prices for books that were subject to the Net Book Agreement [NBA]. In fact, anyone who was sixteen or over when the NBA agreement was abolished, in 1997, will be well into their thirties now. The NBA acted as the linchpin of book retailing for ninety-seven years. It was set up in the year 1900 by a group of publishers who were afraid that booksellers were discounting their publications so heavily that their businesses would become unviable and that so many bookshops would therefore be forced to close down that across the nation there would no longer be an adequate shop window to promote their titles. (This was, of course, decades before internet bookselling and also long before some publishers began to sell direct. The only alternatives to high street booksellers at the time were book clubs (which had a reputation for unscrupulousness) and, until the foundation of the public library service, paying to borrow books by subscribing to circulating libraries such as Mudie’s and Boots.) The NBA declared that no bookseller could sell a book at a price lower than that decreed by the publisher and printed on the cover. After the public library service was given its charter in 1932, an exception was made in favour of allowing booksellers to apply discounts of up to 10% to orders that they received from public libraries.

Also called Resale Price Maintenance, the NBA was effectively a restrictive trades practice. When it was first set up, it was among a number of such restrictive practices allowed by British law; when it was re-examined in 1962, it was one of only two remaining (the other involved the supply of certain products to the pharmaceutical industry). In 1962, it was declared still to be in the public interest. One of the main reasons for this ruling was that it enabled bookshops to stock a wide range of titles; in other words, it stopped outlets like supermarkets and other non-specialist retailers from buying up large quantities of top-selling titles at a discount and passing on this discount to the customer, thereby depriving proper range booksellers of their bread-and-butter income. Ironically enough, the argument for its validity began to disintegrate when Terry Maher, proprietor of the Dillons book chain, illegally began to apply discounts to some titles in 1991. The NBA was re-examined in 1996, when it was declared to be against the public interest and therefore outlawed.

The effects of this were not immediate, because both booksellers and publishers were cautious about dismantling wholesale an implement that had supported their industry effectively for almost a century. However, eventually booksellers began to demand higher discounts so that they could attract customers by offering loss leaders. Only the big publishing houses were able to offer significant discounts and then only for the most popular titles (it is one of the paradoxes of modern bookselling that the titles that are most heavily discounted are the ones that people are most likely to buy anyway). It has since become more and more difficult for small independent publishers to sell their titles into bookshops and, if they do succeed, they rarely manage to get these titles prominently displayed; the net effect of this is that the titles then sell less well than titles that are prominently displayed, which means that the bookseller’s next order to the independent publisher is likely to be even smaller than its predecessor. It’s a vicious circle, exacerbated by the relatively recent practice adopted by some chain booksellers of selling prime in-store display space to publishers. Naturally, only the largest publishers can afford to pay the price. Ergo the ‘W.H. Smith syndrome’ [a slightly unfair soubriquet, by the way, because a) Smith’s does not pretend to be a range bookseller and b) individual Smith’s stores will sometimes go to considerable lengths to promote local authors].

So, should we have allowed the UK’s Net Book Agreement to be first vilified and then murdered? Both France and Germany still operate some form of Resale Price Maintenance on both print books and e-books; both still have flourishing terrestrial bookshop chains and independents that offer range titles. It is also an interesting fact that e-books have been much slower to take off in these countries. Is it in part because RPM makes them more expensive than in the UK? Is this a good thing or a bad thing?

I was particularly fascinated when Apple came up with the agency model as a fair way of selling e-books. The agency model does not fix the price at which the book can be sold, but it does establish the minimum margin that must be made by the publisher. Effectively, like the NBA, it is therefore a form of price-fixing and has been declared illegal.

When you look at the legal reasons for abolishing Resale Price Maintenance of any kind, they seem to be entirely proper. But the argument about what best serves the need of the customer is much less clear-cut. Fine, if the customer wants to read only blockbusters, but for those of us who would like more variety in our reading diet, a mechanism that enables bookshops to stock less popular titles has been proved to be beneficial. Would the reintroduction of the Net Book Agreement therefore be ‘a good thing’? A difficult question, but one to which I am inclined to answer ‘yes’. I am quite certain, though, that, given the present economic climate, it will be a long time, if ever, before we are given the chance to find out.

Fiona Malby (@FCMalby) offers me the chance to post on her blog today!

Author FC Malby (‘Take Me to the Castle’) has given me a precious place on her blog today, March 11th 2013, to write about something very special to me: The Fine Art of Bookselling. Sincere thanks to her for this hospitality!

Proofs positive…

One of the most interesting things about proof copies is that you don’t own them. Most have printed on the cover that they cannot be sold. Some publishers also say: ‘This is the property of the publisher and not for sale.’ Yet I have never heard of a publisher who asked for a proof to be returned. The ones that I have, which represent some of my happiest years, working as the purchaser for a library supplier, will probably stay on my shelves until I die. Then they will be my son’s problem: will he ‘own’ them, or not? I suppose that he will take them on and become their guardian, just as I have been their châtelaine since they were young and untried.

I remember how I acquired some of them. Publishers’ reps get to know their customers’ tastes in literature, of course, and often they would produce two or three proofs from their bags and give them to me; or I would be sent one by post in advance of a launch. The biggest haul always came from Cape, Chatto and Bodley Head. These three companies (which were later swallowed up by Random House) jointly used the same sales team. For a number of years, the representative whom I saw, David Moore, used to drive across the Pennines from his home in Lytham St Annes, spend the night at a hotel in Wakefield and ‘travel’ the Leeds bookshops the next day. As my office was close to the hotel, he would call on me towards the end of the afternoon, just after he’d completed his journey (and in time for a cup of tea). When I’d given him his order, I’d ask if I could have a look in the boot of his car, which always contained two or three boxes of the next season’s titles in proof. I would come away with a rich haul; I was never disappointed.

I keep the proofs on the bookshelves in my study, not downstairs with the finished books. They are actually more precious to me than their suaver counterparts – I have finished copies of some of the titles as well. I have just lifted some of them down. Strange to think that, when they were printed, some of them were obscure titles from young unknown authors who have since become very famous. Of course, some of the authors were famous then: my collection includes The Dwarfs, by Harold Pinter, Mantissa, by John Fowles, Black Dogs, by Ian McEwan and The Temptation of Eileen Hughes, by Brian Moore. I think that all of these writers were well-established at the time. However, I also have 1982, Janine by Alasdair Gray and The White Hotel, by D M Thomas; each of these books catapulted its author into acclaim. Curious to think that I read and liked these brilliant but then unknown works and myself made a small contribution towards launching them upon the world.

I still have a couple of proof copies of In the Family. I don’t flatter myself that in years to come they will be sought after in the way in which some of the titles in my collection are. Nevertheless, it amuses me to allow them to rub shoulders with the great and famous, in some cases in the augenblick before fame came. It is almost like putting In the Family into a time machine.

My favourite bookshop!

Yesterday I visited Waterstone’s Gower Street, which in my mind is called simply ‘Gower Street’ and, in many other people’s, is still indelibly fixed as ‘Dillons’. A great bookshop and, of all the bookshops I have visited (there have been a few), easily my favourite. It’s situated in the heart of Bloomsbury. Approaching from Gordon Square, you come upon it suddenly, an Arts and Crafts enchanted castle before which there is always a litter of student bicycles, as if thrown down in homage at its feet. On an early spring day, especially when the sun is shining, your heart lifts immediately.

The shop was founded by Una Dillon, herself one of the extended ‘Bloomsbury set’. Almost every other door of the houses in Gordon Square and adjoining Fitzroy Square is adorned with a blue plaque celebrating the fact that a Bloomsbury author lived there; Una Dillon created the shop to serve them. The building was originally an early experiment in franchise retailing, a sort of forerunner of the Galeries Lafayette or Selfridges. It was designed to house twenty-four retail units, one of which was initially taken by Una Dillon. Gradually, over a period of years, she expanded until she had bought all of the units and therefore the whole building. (This also lifts my heart: I wonder if there is the remotest possibility that this could still happen today? Could a bookshop oust, say, Zara, Boots, Gap, Marks & Spencer and their ilk from such an ‘emporium’? I have my doubts!) Consequently, behind the scenes, it is a rabbit warren of corridors and small offices. It is also a protected building – of which I’m entirely in favour – although it does mean that not even a nail can be knocked into the wall without English Heritage’s being first consulted.

This shop came under my jurisdiction for several years in the 1990s. At the time, there were booksellers there who could remember Una Dillon’s being wheeled into staff meetings in her wheelchair and who were still in awe of her memory. (I must admit that the image of this is conflated in my mind, unfairly I’m sure, with the image of Jeremy Bentham’s stuffed corpse, similarly wheeled into meetings at UCL nearby, but I’m sure that Una was still alive on the occasions of which they spoke!)

I myself have many excellent memories connected with the shop – for example: the launch for George Soros’s book, which attracted so many people that it had to be held in a lecture theatre at UCL, with a television link to an overspill room; coming out of the manager’s office and finding Will Self chatting to the staff in the reception area; walking back a little dazed to King’s Cross through a summer dawn on a Sunday morning, having – with all of the staff – been up all night stocktaking. And it is still my favourite place for browsing and buying books.

Great bookshops are like people – they have personalities. A great old bookshop like Gower Street also has secrets. As far as I know, there has never been a murder committed there, but there could have been. Maybe someone will write a novel about it!

Fabulous: a book festival!

I am delighted to have been asked to chair the crime writers’ event (at Watton Library in Norfolk), which takes place as part of the Breckland Book Festival on Saturday 16th March. It’s a session that features Tom Benn and Elly Griffiths.

Yesterday Claire Sharland, one of the organisers of the event, got in touch to suggest that I should read their latest novels, Chamber Music (Tom) and Dying Fall (Elly), before the session and generously added that the festival would pay me for the purchases. I am delighted with this offer – I shall buy the books when I am in London next week. I’m sure that, very shortly, I shall also be reviewing them on this blog!

It’s always nice to be given some books, especially if you buy them all the time. I’ve long been amused by the Booksellers Association’s definition of a ‘heavy book buyer’ as someone who buys twelve or more books a year – most years, I barely get through January without hitting this figure. What really excites me, however, is that someone has prescribed my reading for me. I’m going into this totally blind – I haven’t been prompted by reviews, word-of-mouth recommendations or even by spotting the titles in a bookshop. Aside from examination texts, I can’t remember when I was last instructed in what to read in this way. It might have been during my third year at high school, when the class text was My Family and Other Animals, by Gerald Durrell. My bookish, priggish thirteen-year-old self turned up her nose in disdain when sets of this were distributed. I didn’t think it was suitable ‘serious’ reading for someone who, while still at primary school, had read such classics as Jane Eyre, The Thirty-Nine Steps and Great Expectations, especially as – distasteful innovation – the school copies were in paperback!

It’s a pity that I didn’t adopt such a fastidious approach to every subject. Today I wouldn’t be able to recognise a quadratic equation if it bopped me on the nose; and I’ve never mastered the mysteries of algebra (though it now occurs to me that it could be a useful vehicle for plot construction: let x be the murderer, y the victim, z the wicked stepmother etc.).

I should add that my precious teenage prejudice against My Family was immediately dissipated by reading its delights; I’ve read it several times since and it was one of the books that I read to my young son at bedtime. I’m certain that I shall like Tom’s and Elly’s novels, too, and look forward to making their acquaintance, first through their work and secondly in person. If anyone reading this should happen to be in the vicinity of Watton Library at 3 p.m. on 16th March, I hope perhaps to meet you there, too.

Making the most of the best of social networking!

Today’s post is, in fact, a ‘shout-out’ about a Salt Publishing seminar at this year’s London Book Fair, giving an opportunity to listen to Chris Hamilton-Emery, founding director of this world-renowned independent publisher, and three of its authors talk about how to use social networking to promote books and good writing. There will be a question-and-answer session to develop discussion about the topic How to Build Social and Brand Equity on a Shoestring. Elaine Aldred, an independent online reviewer, will chair the occasion.

Date: Tuesday 16th April 2013

Time: 11.30-12.30

Place: Cromwell Room, EC1, Earls Court

I’ll be joining Katy Evans-Bush, writer and editor, and Elizabeth Baines, novelist and short story writer, to offer some personal experiences of social networking as a means to achieving an online bookworld presence. Readers of this blog will already guess from previous posts here about both Salt and social networking, how much I personally value the opportunities provided by the Internet to meet and mingle with booklovers across the world. I have also made it very clear just how proud and privileged I am to be supported as a writer by Chris Hamilton-Emery and how exciting it is to be associated with an independent publisher with the finest of literary lists.

I hope to become real to at least some of my ethereal friends at the London Book Fair this year!

The murky world of the bookshop…

I have interviewed many would-be booksellers… and appointed quite a few. Candidates often have a misconception of what bookselling is about. Every bookshop manager will have experienced that sinking feeling when an enthusiastic prospect earnestly says, ‘I love books.’ Most bookshop-lovers will have had at least one experience of waiting patiently for service while the bookseller sits back from the till, absorbed in a good read. I’m not knocking booksellers, though – far from it. I’ve known very many excellent ones and one or two who could be described only as geniuses. Yet, without exception, however much they have loved books, their passion has been for serving real people from all walks of life, often by providing the book that is being sought, but also frequently by suggesting one that the customer would never have found without their expert skill and intuition. Good bookselling is all about caring for the customer.

I’m digressing a little, however, because I meant to begin by saying that the popular perception of a bookshop is probably that it is a quiet haven of peace where nothing much happens, a place in which to relax and browse and take a little time out from the humdrum demands of everyday life. And this is how it should be; I know many bookshops that can create such an ambience and I’d be proud to own one myself.

However, as with any other organisation or enterprise, within the inner life of bookshops is concealed – and sometimes, unfortunately, revealed – a maelstrom of human emotions and behaviour. I think that it is likely that there is more intrigue going on in bookshops than in any other kind of retail business, because most booksellers are well-educated and well-read and excel at being creative with their time. Mostly, this wealth of ideas and inspiration is channelled into supporting the shop and making it unique. Very much more rarely, it assumes a deviant quality.

Theft is a despicable crime. It isn’t much written about by crime writers, perhaps because it isn’t ‘glamorous’ enough. Persistent theft from a bookshop will kill it as surely as acute oak decline will fell a mighty tree. The reason for this is that bookshops operate on wafer-thin margins. Therefore activity that persistently undermines the profit of the shop will not only hasten it towards closure, but also demoralise the staff. In most bookshop chains, the staff (not paid a fortune in the first place) are disqualified from receiving bonuses if so-called ‘shrinkage’ reaches a certain figure – usually three-quarters of one percent of turnover. Some book theft is casual and opportunist; some is highly-organised. One of the bookshops in East London that came under my aegis suffered for months from the carried-out-to-order stealing of the textbooks that supported certain courses at the local university.

Of course, there are sophisticated systems available which help to reduce the risk of theft, but it is surprising how wily some thieves can be. A bookseller in another of ‘my’ shops apprehended a man who was wearing a specially-adapted overcoat that could hold twelve average-sized volumes at a time. He was spotted spending an undue amount of time riding the lift, where he had gone to rip out the security tags.

Some bookshop theft, the saddest kind, is ‘internal’, i.e. carried out by one of the members of staff. I hasten to add that it is comparatively rare, but when it happens it is the most difficult kind to discover, because the perpetrator is familiar with the shop’s systems and routines. The largest bookshop that came within my remit, one that turned over millions of pounds a year, had been suffering from serious shrinkage for some time when we decided to fit tiny security cameras over some of the tills. We quickly discovered that one of the cashiers had been operating an elaborate scam. (I won’t say what it was, as it would still work now, if someone were prepared to try it again.) She was brought to the manager’s office, told that the police would be called and asked if she wanted anyone to be with her when they arrived. She asked for her husband and he was summoned.

I had thought that perhaps he had been her partner in crime, but when he arrived he was genuinely stunned to discover that his wife was a thief. The police had yet to turn up. We waited rather tensely. I asked her if there was anything else that she wanted to tell us.

To my utter astonishment, she said that there was. There has been a handful of occasions in my life when I have been truly gobsmacked, rendered speechless, shocked to the core, whatever the appropriate term is. This was certainly one of them. The shop was adjacent to a large university and an intranet had recently been set up to allow academics to place orders and ask for advice without having to leave their desks. The woman standing in front of me now confessed that she had been using this facility in order to run a brothel. Most (but not all) of the clients worked at the university. Perhaps at this point I should pause to say that I am not exaggerating a word of this and, when an investigation was carried out, all of the details that she gave proved to be true.

The intranet was closed down immediately, though, on police advice, no further action was taken about the ‘business’ that it had been used to support, because the complications, notably the risk of implicating innocent people, were too great. The bookseller was charged with grand larceny (far too aristocratic a name for such a tawdry crime) and, because she had stolen a large amount of money over many months, received a custodial sentence.

I still think of this quite often. She was a pretty, vivacious young woman who had a presentable husband, himself with a very good job. It came out in court that she was not in debt and enjoyed good health and a comfortable lifestyle. Why did she do it? Why did she expend her considerable intelligence on working out two quite ingenious ways of making money illegally (one of which directly harmed her colleagues), instead of concentrating on developing her career or retraining if she felt dissatisfied with it? Perversely, perhaps, there was something about her that stirred pity in me, too. Did she survive prison well? Was her husband waiting for her when she came out? Did she succeed in rebuilding her life? I shall never know the answers.

Finally, before you worry that I have taken to cutting up my own novels, this one was a stray proof. I was asserting an author’s editorial privilege.