An admission of ignorance…

A web-developer named Christopher Pound has carried out a text data mining trawl (I shall write about text data mining in another post – it is a bit of a hot topic in some publishing sectors at the moment) to reveal the 100 most popular books by different authors to be accessed via the Project Gutenberg free e-book site. Books for both adults and children are included. The top 10 from both categories are:

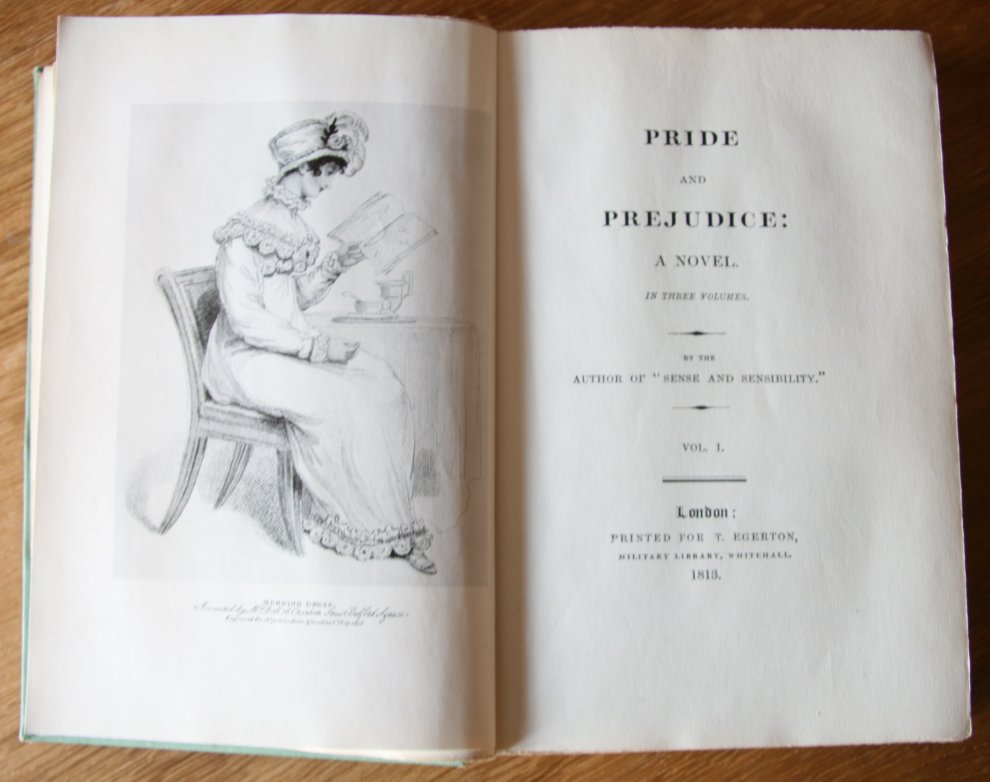

1 Pride and Prejudice (Austen, Jane)

2 Jane Eyre (Brontë, Charlotte)

3 Little Women (Alcott, Louisa May)

4 Anne of Green Gables (Montgomery, L. M. [Lucy Maud])

5 The Count of Monte Cristo (Dumas, Alexandre)

6 The Secret Garden (Burnett, Frances Hodgson)

7 Les Misérables (Hugo, Victor)

8 Crime and Punishment (Dostoyevsky, Fyodor)

9 The Velveteen Rabbit (Bianco, Margery Williams)

10 Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Twain, Mark)

Can you spot the odd one out? Or am I just revealing my own crass ignorance when I say that I have never heard of The Velveteen Rabbit? According to Wikipedia, this book, which was published in 1922, was selected as one of ‘Teachers’ Top 100 Books for Children’ by the (American) National Education Association in 2007. Apparently it has also been the subject of numerous film adaptations, talking books, etc. Wikipedia sums up the plot as follows: A stuffed rabbit sewn from velveteen is given as a Christmas present to a small boy, but is neglected for toys of higher quality or function, which shun him in response. The rabbit is informed of magically becoming Real by the wisest and oldest toy in the nursery as a result of extreme adoration and love from children, and he is awed by this concept; however, his chances of achieving this wish are slight.

Peter Rabbit, Alice in Wonderland, Heidi and Uncle Tom’s Cabin all appear in the Top 100, but considerably lower down in the list.

Statistics like these always make me want to know more. Why has The Velveteen Rabbit proved so popular, at least when accessed via Project Gutenberg? It isn’t because it’s not available in print: Amazon lists it and states that there are both print and talking book versions available. Is it because American teachers are more likely to direct pupils to e-book sites than teachers in other countries? Do they perhaps even download it and arrange for it to be printed for their classes via a Print on Demand company? Or, as I’ve suggested, is it just that there’s been a blip in my education? In fact, several blips, because in all my years as a bookseller and library supplier, I have never come across either this book or its author.

Here is Christopher Pound’s full list.

Prince Charles and I are not of one mind…

I love old houses and have been visiting stately homes since I was a child. I celebrate them as a unique part of our English heritage and I am always fascinated to read about the people who lived in them and to gaze upon their portraits. I’m making this clear at the outset, because what I’m about to write may seem a little out of character, not to say controversial.

I read in last Sunday’s Times that Prince Charles is throwing his considerable weight behind the fight to save Wentworth Woodhouse, which requires £100m to be spent on it to conserve the building and reverse subsidence. By a strange coincidence, some years ago, the Prince intervened even more directly to save Dumfries House, by spending £20m from the Prince’s Trust on its renovation. I say coincidence, because for three years I worked in Dumfries and had a flat there, so I’m familiar with and have lived near both the old piles in which he has taken an interest. (If he starts campaigning for any more such buildings near me, I shall begin to think that he is stalking me!)

Wentworth Woodhouse is not so very far away, though I’ve only visited it once, and then only the grounds, because until recently the house wasn’t open to the public. At the time of my visit, about five years ago, it wasn’t possible to get close to it: it had to be viewed from a public footpath on the other side of the boundary fence. I didn’t in fact know of its existence until the publication of Black Diamonds, by Catherine Bailey, which I bought after reading rave reviews when the book came out in 2008 and which is a meticulously-researched account of one of the families that lived in the house – so it doesn’t cover the whole of its history, but I found Bailey’s account gripping and it inspired me to want to see the mansion for myself.

Wentworth Woodhouse has been described as Britain’s finest Georgian house. It is certainly its largest. The main front of the house is 606 feet long, twice the length of Buckingham Palace. It has more than 1,000 windows. The newspaper article says that the nursery was situated an eighth of a mile from the dining room. Guests were given different-coloured confetti so that they could find their rooms again when they retired to bed (I remember reading this in Bailey’s book, as well). Even the stables are huge: in common with many other visitors, I mistook them for the house itself when first I came upon them. In fact, huge is the best word that I can think of to describe Wentworth Woodhouse itself: or gigantic, or enormous, or gargantuan, or outsize. In my view, it is both a monster and a monstrosity. It is gratuitously massive just for the sake of it. It has been symmetrically constructed, with two elongated wings, but is not otherwise architecturally distinguished. It actually gives the impression of being rather squat, even though the main building is three storeys high, because of its preposterous length. If it had been built today, say by an oil sheikh or a Silicon Valley magnate, I’m sure that it would be denounced for its vulgarity. Wentworth Woodhouse is a white elephant. I do not think that it merits the expenditure of £100m to preserve it, especially as I’m sure that this would be just the beginning. Despite the present owner’s ambitious plans to develop several commercial ventures there, I cannot imagine that it could ever be self-sustaining. £100m is a colossal sum of money and would, I feel, be better spent on saving many ‘lesser’ buildings instead.

There is another reason why I hold this view. Wentworth Woodhouse has been one of the most bitterly socially-divisive buildings in our history. I don’t mean the usual upstairs-downstairs disparities illustrated by soap operas like Downton Abbey, about which we probably feel far more uneasy than the people who lived and worked in such houses at the time. Wentworth Woodhouse was built on coal – both literally and metaphorically. The house sits on what was once a rich coal seam. Generations of its owners met the massive expenses of its upkeep by selling the mining rights to the coal that lay deep below its lands. The nearby village of Elsecar was a coal-mining village. Its inhabitants either mined the coal or worked at the house itself. It is still a pleasant but modest village that contains no large properties; the only large property for miles around was Wentworth Woodhouse itself.

The Fitzwilliam family, which owned the house for most of its history and whose story Catherine Bailey tells, were on the whole kind employers, even though the sons sometimes exerted droit de seigneur and fathered a few bastards on the local girls. By the time of the Second World War, its glory days were long over. After the war, it fell victim to what can only be described as an act of vandalism fuelled by class hatred. In 1946, Emmanuel Shinwell, the ruling Labour Party’s Minister of Fuel and Power and a man of extreme proletarian views, insisted that open cast mining should take place on the estate, even though the richest of the coal seams were not close to the surface. He stopped short at demolishing the house itself, but the debris from the mining was actually banked up against its windows. The grounds and gardens were completely wrecked.

Wentworth Woodhouse is now owned by one Clifford Newbold, who bought it for £1.5m some years ago and has since spent more than £5m on carrying out as much repair work as he says he can afford. He is now seeking to sue the Coal Authority for £100m for the depredations to the house and estate that resulted from Shinwell’s instructions. This is the initiative that Prince Charles is supporting. To me, it seems like an invidious and depressing resurrection of a vengeful class war that played itself out almost seventy years ago and from which I should prefer to believe that we have learned and moved on. In addition to this, whether or not the lawsuit is successful or funds are raised to restore the house by some other means – for example, via the National Lottery – it will be the nation itself that pays. One way or another, that £100m will ‘belong’ to us. Do we want to spend it on Wentworth Woodhouse? I suggest that we don’t. This not-so-old, not-so-beautiful, enormous house has been the scene of many past crimes on both sides of the class divide: generations have toiled below the ground there in inhuman conditions, and many miners lost their lives working the Barnsley coal seam; young girls had their lives ruined by the stigma of bearing illegitimate children to an elite of young men impossible to refuse and the upper class occupants of the house suffered the trauma and indignity of being reviled and trapped in their pile by the evangelical social engineering of a scion of the Glasgow working classes. It has not been a happy place, nor a place where greatness has flourished.

It is my belief that, like other places that have been the scene of great pain and suffering, Wentworth Woodhouse should be allowed to die, not a death by a thousand cuts, as money is successively raised and then exhausted, but in one final burst of theatre, one last grand gesture. I think that Wentworth Woodhouse, like many another ageing building, should make its exit via a blast of dynamite and tumble to the ground with dignity, like a huge beast that has now lived out its natural span.

Controversial, maybe. In some ways, I am surprised at myself. But I do believe this, strongly.

The murmuring of innumerable bees…

Yesterday I went on a pilgrimage to Ripon with my husband, in quest of bees. We (I say ‘we’ – he is the bee-keeper, the one who has acquired the considerable amount of scientific knowledge needed and has the requisite patience; I am the bee-keeper’s assistant, so can get by on more limited quantities of both and shirk my duties if I feel like it.) started keeping bees a number of years ago, with reasonable success. However, the terrible winter and very wet spring here took their toll and, like many beekeepers, we suffered losses.

Because, according to the press, some 80% of the nation’s bee colonies perished this winter, ‘supply and demand’ now dictates that the cost of a ‘nucleus’ colony is very high (up to £250) and it’s definitely a sellers’ market. Hobby beekeeping isn’t cheap anyway, with hives, frames and beekeeping paraphernalia. The equipment is, to me, like something designed by Heath Robinson or Rube Goldberg and I’m not surprised it’s pricey, given the frankly bizarre design of smokers, heated honey-capping knives, centrifugal honey extraction drums and solar wax melters; the few existing suppliers who have cornered the market definitely call the shots. Anyone thinking of starting up should throw those rose-tinted, back-to-nature, self-sufficiency specs away and go for crystal clear lenses. Then there are the bees themselves: they aren’t like kittens; they don’t come out to melt you with their charms when you are trying to decide whether to offer them a home and they don’t take kindly to being shipped by car and bumped around, before being hoiked out of one temporary home and bundled into another. Though some strains of bee, such as the Italian ‘ligustica’, are more gentle, bees tend to be ‘mongrels’ with very variable temperaments; sometimes a queen bee has genes with an attitude problem. So, though you might dream of summer days and drowsing in the garden sunshine, imagining yourself transported to the Mediterranean by the murmuring of the apiarian equivalent of the Italian soldiers in Captain Corelli’s Mandolin, the reality can be more like taking on the aliens in Independence Day or WWII kamikaze pilots, hell-bent on taking you out even at the cost of their own lives. Think high-pitched incoming whine and be prepared to take cover. Unhappy bees do not subscribe to the concept that assault and battery is a crime. They just do it.

However, for those of us who do love bees and have become used to their temperamental ways and needs, caution is the watchword, and we pulled the plug on the travelling box and retreated quickly to a very safe distance. They’ve settled in already. Apparently, they get their bearings by flying backwards the first time that they leave the hive, to note where they are as they look back on it. They are remarkable creatures: they’re incomplete individually, but together comprise what is known as a superorganism. Each worker has her own task to perform and this changes over time as she ages, becoming finally a nectar- and pollen-gathering ‘forager’. The male ‘drones’ have their moment of glory, flying with the virgin queen to enable her to mate with several of them, before dying a gloriously sexy death (genitalia ripped right out of them!), or never doing anything until they are kicked out by the workers in the autumn so that they don’t deplete precious food reserves over the winter. I’m not a feminist by any means, but I can think of a few men whose families would benefit from similar summary treatment!

Because of the way in which they organise their lives and collaborate, bees have cropped up in art and literature from earliest times. Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics feature bees; the early Greek writers celebrated them in song and verse. In more recent times, Alexandra Kollontai used the bee colony as a metaphor for life and love in Russia in the aftermath of the 1917 revolution, in her masterpiece Love of Worker Bees.

Bees are a joyful trouble. If they’re successful, they swarm, and the bee-keeper, in hot pursuit, has to shin up trees or plunge into thickets, hanging on precariously with one hand as he tries to trap them in a traditional straw ‘skep’ or a cardboard box. (You notice I say ‘he’ – this is emphatically not this beekeeper’s assistant’s job – though I know that there are many very skilled female beekeepers.) They suffer from a parasite called varroa mite, on which war has to be waged all the time if the colony is to flourish. Bees eat unconscionable quantities of sugar syrup during the autumn and often yield only a few small jars of honey per hive in return, but the benefits of their wider gifts to agriculture and the environment are incalculably great.

And I have to admit, in spite of all those expenses and troubles, now that the garden is once again a-buzz with murmuring bees, it feels as if the summer has begun in earnest at last.

The spurs have it…

Some creatures capture the human imagination more readily than others. Hares have always been magical, perhaps because of their singular behaviour during the spring, perhaps because of the magnificent way in which they will sit up on their hind legs in a field, catch a whiff or a glimpse of danger and bound away, leaping and weaving, ducking and taking advantage of cover and terrain, to throw any would-be pursuers off the scent; most mystical of all, the near-silent pair dance through a woodland glade, for once so mutually bonding that a standing human watcher is passed unnoticed. By comparison, the rabbit is streets behind in the enigma stakes. He shuffles and bobs about, waving his scut ineffectually and, as soon as he takes fright, scampers off with no pretence at dignity or even of making a measured retreat.

Domestic animals exercise similarly varying effects upon the fancy. I’ve never been close to horses, but I can see why people say that they’re noble. There’s a certain stolid majesty about cows as they stand grazing and gazing; pigs endear with their uncannily human-like squabbles. However, farmyard animals generally don’t bring with them the same depth of historical literary allusion, maybe because writers of earlier generations were more accustomed to draw their metaphors from the wild, maybe because we know that the cows and pigs and horses of, say, late mediaeval England bore only a generic resemblance to the ones that we see today. For at least the last two hundred years animal husbandry has involved the intensively selective breeding of farm animals in order to accentuate their most marketable and productive features: today’s cows and sheep are very different from those that feature in eighteenth century paintings; pigs are bred to yield less fatty meat as dietary preferences change. There’s also often a kind of placidity about the creatures found on the modern farm, as if they understand and have accepted that their purpose in life is to bend to the will of their human masters in return for plenty of good food.

Bulls are an exception, of course. I’ve known some very tricky bulls, especially those unpredictable Channel Islands fellows, only too ready to vent on unwary passers-by their frustration and bad tempers. When a bull catches your eye and rolls his own, stamps his hoof and tosses his head – or makes any of these movements – you know at once that discretion is the better part of valour and that, if there is no stile nearby, your best bet is to dive over the nearest hedge or barbed wire fence, a few nasty scratches being preferable to serious injury or death. Bulls in stalls can be even more irate and the escape routes more limited; during my youth, I knew of several Lincolnshire farmers who were gored by bulls in the byre, one of them fatally. The bull does not take kindly to having his masculinity compromised. Yet still they are domesticated, at least in the sense that they look nothing like their forbears.

One creature, however, that evokes for me all the mystery and romance, the pomp and pride as well as the murderousness, of the Middle Ages, is the cock. I’m well aware that chickens have also been subject to generations of selective breeding techniques designed to improve either the laying-power of the hens or the quality of meat for the pot; yet a proud cock, strutting among his hens, still seems to carry the primeval stamp of his ancient forefathers. He shakes his comb and wattles menacingly at impertinent human observers; he preens and poses in the midst of his harem, spurs sharp and threatening. He is a fighter; barbarously, his fighting instinct has been exploited by men until quite recent times. It is the cock who, through the ages, has serenaded the dawn and it is for this, above all else, that he has secured his pole position in the literary canon. From Aesop’s fighting cocks to the rooster after whose third crow Simon Peter betrayed Christ (unusually, all four Gospels agree about this), to Chaucer’s Chauntecleer to stories from other cultures, such as the generations-old Indian story of the cock and the hen, cocks have always crowed and have always been part of myth and fable, woven by talented narrators into great tall stories.

I met a particularly handsome Chanticleer yesterday, when visiting one of my oldest friends, who lives in Lancashire. I’ve taken his picture. Chaucer would have loved him.